Varda describes Jane B. par Agnès V. (1988) as a kaleidoscope film,[1] a film of various stories, over various seasons. It is a film of coloured facets, falling shards, about a varying woman, a starlet, an icon, Varda’s friend Jane Birkin. Unlike a conventional film homage to an actress, rich with clips and tributes, this collaborative project, an imaginary archive of Birkin, comprises new scenes from imagined films, scenarios in which Birkin might have, or would have like to have, starred. It creates a repertory to meet Birkin’s desire and to realise her possibilities. It intersperses imagined scenes with interviews between Varda and Birkin, living and alive, in moments of apparent intimacy and limpidity. In among its ways of imaging Birkin, of approaching her, the film returns to the figure of the reclining nude. This is the image Varda chooses as she responds to an actress who is her intimate friend and who is also a beautiful, notorious, and fragile star. The figure of the reclining nude allows Varda to attend to and reflect on Birkin’s erotic appeal, her pliability, her aura of nymphet and femme enfant, her availability, and provocation.

Jane B. par Agnès V. is a film about apprehending another woman’s impressionability. This is its feminist curiosity. It acquires poignancy as a portrait about mortality and vanity, responding to Birkin’s nearing the age of 40. The film is dedicated to Jane Birkin, with love, with kisses, on her fortieth birthday. Critical to the film is Birkin’s particular vulnerability at this age of her life. Interviewed in Varda par Agnès, Birkin explains her feelings of fear surrounding 40: «cela m’apparaissait surtout le moment où la peur de perdre des êtres chers vous prend [it seemed to me above all the moment when you feel the fear of losing loved ones]».[2] Her fear comes in her sensing of the fragility of life, in her apprehension of her loved ones as damageable, impermanent. It is this vulnerability that draws Varda’s interest. She explains in the same interview:

Moi je trouve […] que la quarantaine est un âge magnifique pour les femmes parce que – justement à cause de leurs craintes – elles sont vulnérables. Je crois fermement que la peur de quelque chose rend les gens plus sensibles [I think 40 is a wonderful age for women because – precisely on account of their anxieties – they are vulnerable. I firmly believe that fear of something makes people more sensitive].[3]

Varda validates vulnerability as it produces a new sensitivity and impressionability. She says that her aim was to reassure Birkin.[4] She seeks to reassure her about ways of living in vulnerability, about the passage of time, about loss.

The poignancy of the film is quickened by the recognition of all that is childlike, natural, disarming, and erotic in Birkin, and the apprehension, never voiced, that these qualities will be lost. The film captures moments of evanescent loveliness and also envisages pursued sentience, liveliness, desire, not least through the creative presence of Varda herself. Varda says of Birkin in the film, «elle a été drôle, étrange, magnifique, pathétique [she was funny, strange, magnificent, moving]».[5] Varda offers a gift to Birkin of a faceted portrait, a series of mirroring reflections that show life as transient, as passing, and as painful and resplendent.

For Varda Jane B. par Agnès V. is a film about transience, «sur le temps qui passe, sur les saisons, sur les maisons [on time passing, on seasons, on houses]»,[6] and as such it fits with her interests in the seasons in other films. Its opening words are about time passing, as she describes a Titian painting she has rearranged into a tableau vivant: «c’est une image très calme. Hors du temps. Tout à fait immobile. On a l’impression de sentir le temps qui passe, goutte à goutte, chaque minute, chaque instant, les semaines, les années’ [the image is very calm, timeless, motionless. Yet time seems to be passing, drop by drop. Each minute, each second, weeks, years]. For Flitterman-Lewis, this film is «pure gold».[7]

In a coruscating article on the portrait of the artist in Varda, Mireille Rosello writes:

In Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse she invents a season, a moment that we could call ‘the season of gleaning’ and which establishes a powerful – albeit untold connection, between death and gleaning. Just as we can see Sans toit ni loi as a story about winter, about the cold, so Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse is a film about a season that does not exist, an after-season. When the land has produced its fruit, a moment of dormancy begins, a hiatus, or in-betweenness. Grapes and apples have been picked, the wheat has been harvested, and between the end of that process and the beginning of a new stage of preparation, Varda inserts her story.[8]

This season of gleaning is its own season. Rosello sees it as a moment of dormancy, a hiatus. This is what Varda has created also, differently, as she spends time, across the seasons, with Birkin in Jane B. par Agnès V. In this film of Birkin, Varda shows a period of dormancy between the quickness of childhood and adolescence, and full-blown existence and vulnerability as a woman. Varda lays Birkin out, a reclining nude, and she is all ages, child and mother, erotic icon and mortal, a woman now fragile as she feels vanity, imminent loss, time passing. The film’s capture and dilation of time is mesmerising. Varda’s filming looks forward to the precious encounters with Jacques Demy in Jacquot de Nantes (1990) where there are diaphanous images of Jacques still living, the sand passing through his fingers.

The films do not stop time, or fetishize the past, but rather open moments, seasons, outside time, moments for contemplation, intensity, dormancy, stillness. Time will move on, but the films cherish this richness, heightening, instantaneity stretched out. In her television series about photography Une minute pour une image (1983), Varda chooses an image by the photographer Gladys, Série du canapé [Sofa series] (n. 6) (1978), where a couple make love in the afternoon, their bodies cocooned. They recline, extended, nestling on the sofa. In voice-over Varda says:

C’est comme un frisson d’amour. Ici deux êtres se touchent, s’enlacent, et leur étreinte fait trembler l’air, fait tomber les feuilles, fait s’envoler les oiseaux. Ici, en une minute, c’est un 5 à 7. On sent passer les quatre saisons et les trois âges de la vie et les 32 positions et les 36 chandelles. Cette image c’est en même temps la tranquillité d’un canapé confortable […] et l’instabilité du transport amoureux, avec ce bougé flou qui dessine une chevelure flamboyante à l’un des deux amants. […] L’après-midi va s’achever, les feuilles vont se poser à terre, les cheveux et les choses vont devenir nets. […] L’heure de l’amour aura passé. Mais pour le moment ça vibre encor.

[It’s like a shiver of love. Here two beings touch, embrace, and the air quivers, leaves fall, birds take flight. Here, in one minute, is an afternoon delight. The four seasons and the three ages of life pass in a myriad of positions and starry visions. The image is both the tranquillity of a comfy couch […] and the flux of amorous transport, in the blurry movement of one of the lovers’ thick hair. […] The afternoon will soon end, the leaves will fall to the earth, the hair will come into focus. […] The hour of love will have passed. But right now they’re still vibrating].

This is a time that will be left behind, but that is still alive here. This is the time of Varda’s portrait of Birkin.[9]

In her short introduction to the film, Varda says that she takes the theme of the painter and model. She is the painter and Birkin is her model. Varda finds these words to describe her relation to Birkin: «on était complices, celle qui filme, celle qui est filmée [we were in it together. She who films and she who is filmed]». Varda explores this complicity by recalling earlier images of women in erotic and supine representation. She returns to a tradition in Western painting, animating its seductive figure, opening Jane B. par Agnès V. to the dreams and nightmares of a reclining nude. She enters into dialogue with these images, allowing them entry into her film world as beautiful objects. This engagement encourages vigilance and self-awareness, as Varda adopts and questions the role of the artist and her model.

In Adriana Cavarero’s account of storytelling and selfhood, Amalia writes the story of her friend Emilia and gives it to her as a gift. Emilia is overcome by emotion. Cavarero explains: «Emilia had continually recounted her story, in the most disorganized way, showing her friend her stubborn desire for narration. The gift of the written story is precisely Amalia’s response to this desire».[10]

Amalia’s narrative gives Emilia’s life a tangible form and her story gives Emilia overwhelming pleasure. Cavarero imagines complicity between the two friends and a common desire: «[Emilia] weeps because she recognises in that narration the object of her own desire. Autobiography and biography come thus to confront each other in the thread of this common desire, and the desire itself reveals the relation between the two friends in the act of the gift».[11]

In Jane B. par Agnès V. the filmic portrait is also figured explicitly as a gift, on Birkin’s birthday. For Varda, as for Cavarero, a fuller, more tangible portrait may be achieved by another. Something richer and stranger emerges as others tell our stories. Cavarero and Varda meet on the same terrain as they think through the ways in which we always appear before someone else, in which we co-exist. They both pay attention to the feminist possibility of women making each other’s stories apparent.

Jane B. par Agnès V. opens questions about what it feels like to have your desire perceived by another. It meditates on what it implies to have your self-portrait presented to you in tangible form. There are questions here of not recognising oneself. But also, more pressingly, if the portrait is true, questions of the rupture of looking at your own truth, your own desire, held open and made visible by another. These issues begin to fall into place in the film’s first dialogue between Varda and Birkin.

This dialogue occurs after a sequence illuminating Birkin’s glamour. She is seen in showy, gossamer shots on the Champs-Elysées, accompanied by the song The Changeling by The Doors. Uptown, downtown, Birkin’s movements are free, elated, and involved with the image she is projecting. A moving camera follows Birkin in an arc, always in line with her as she circles the roundabout at the base of the Avenue. In these evening shots a technician runs in front of Birkin, lighting her, and she and he are complicit in their moves. Thickets of Christmas trees are behind her, white with floodlighting and pearl baubles. There is the gush of a fountain. Birkin crosses several radiating streets until she reaches the Champs-Elysées, the trees garlanded with lights and traffic stretching behind her to the Arc de Triomphe. The titles of the film are superimposed over the image of a mirror circled by coloured bulbs. Lights of the traffic are seen moving in the mirror, as the spangles of the trees are now in blurred reflection. Birkin’s stardom is a light show, a tableau vivant with illumination.

Birkin enters the glass doorway of a Paris bar. The space itself is kaleidoscopic, faceted, situated on a corner with panes of glass skirting the curve of the street and a further glass-panelled area opening out behind. The camera is set back at one remove, to show Varda sitting alone and Birkin approaching her. They are both in profile against different panes of glass, facing each other, but with obstacles – a table, a door-frame – in view between them. Despite the careful composure of the shot, the mood is casual, the setting quotidian. In this setting Varda asks two questions. She asks whether Birkin likes being filmed, and she asks whether she likes talking about herself. Exposed here are questions of what Birkin consents to, of the contract between Varda and Birkin in the making of this film.

Birkin seems rushed, ill-at-ease. She says initially that she likes being filmed. She explains: «parce que j’aime le jeu avec le metteur en scène, ce qu’il veut de moi [because I like playing the game with the director, finding out what he wants]». She likes finding out the director’s will, his wish. There is a desire to be given over, to be choreographed by another. She is seen to be absorbed in knowing how she may be perceived, desired, imagined. She also expresses reservations: «je ne sais pas vraiment les règles du jeu [I don’t know the rules of the game]». Her work as actress throws her into the unknown, allowing another to be in control. If this is fun, it is risky.

The focus stays still on Birkin during her replies. She is shy, disinclined to look into the camera. She speaks of her own unknowing with Varda too: «avec toi je ne savais pas à quoi m’attendre. [what will you ask me?]». Varda remarks that in photos and interviews she has seen Birkin never looks into the camera. In the next shot Birkin is in profile, not looking into the camera. The film shows the gaping hole of the camera lens centre screen. Then Birkin says, looking now straight into the lens: «c’est trop personnel [it’s too personal]». She is flushed. It feels as if she is focusing on keeping the lens in her field of vision. Her shyness makes her vulnerable. Her willingness to meet Varda’s desire is suddenly disarming.

The film cuts to an image of Birkin looking at her own reflection in an antique mirror. Varda says: «c’est comme si moi je filmais ton autoportrait [i’m filming your self-portrait]». She says that Birkin will not be alone in the mirror. There will be the camera, which is partly her, and there will also be Varda herself in the mirror. Varda reassures her: «ce n’est pas un piège, je ne veux pas te pièger, te coincer [I don’t want to trap you, to corner you]». The film shows threat, shyness, and also exposure, performance, pleasure. Birkin’s desire is fragile, volatile. Varda’s move is at once to reveal and reassure.

Varda shows Birkin before a real distorting mirror. Her head is stretched pliably in the reflections, expanded and excised, disappearing in the distortion of the image. This elasticity allows a further extension of the contract between them. Birkin speaks of her willingness to be deformed: «moi, si j’accepte qu’un peintre ou qu’un cinéaste fait [sic] mon portrait, je veux bien me déformer [if a painter or a filmmaker wants to do my portrait, I don’t mind distortion]». She submits to this if she is confident in the artist, as she implies she is with Varda:

C’est comme avec toi. L’important c’est l’oeil derrière la caméra ou la personne derrière la brosse à peinture. Je m’en fous un peu de ce que tu fais avec moi, du moment que je sens que tu m’aimes un peu iIt’s like with you. What counts is the eye behind the camera, the person holding the paint brush. I don’t care what you do to me, as long as I feel you like me].

Birkin wants to be liked. She wants to be perceived as lovely. Later in the film, when her wishes are shown more frankly, she says: «je veux plaire à tout le monde’ [I want everyone to like me’]» and «je veux bien avoir l’air sympathique, enfin, naturel [I want to be nice, natural]» and «etre aimée, populaire [‘I like being loved, popular]».[12]

The film she makes with Varda is to work as an enchantment gaining lustre from its indulgence of Birkin’s wanting to be liked, this meeting of an appeal. Varda asks Birkin why she thinks she, as director, wanted to make this film. She replies that it is because Birkin is beautiful. There is a meeting of Birkin’s desire here, a moment where Varda gives her what she wants. But the film also shows up this need, Birkin’s desire to be wanted. The film exposes Birkin’s craving and Varda’s calm meeting of this.

Varda responds to Birkin’s beauty and also conceptualises it: «comme la rencontre fortuite sur une table de montage d’une androgyne tonique et d’une Eve en pâte à modeler [like a chance encounter on an editing table between a tomboy Sloane Ranger and a plasticine Eve]».[13] The words let meanings fan out, anticipating images to come of Birkin as nude Eve remodelled across a series of tableaux vivants, and as nymphet and star in London and Paris. Lability, stretchiness, as figured in the surreal moves in the mirror, are key to Varda’s vision here. The film to come, languorous and acute, will stretch out Birkin’s skin across its series of distorting reflections.

Varda’s choreographing of Birkin, the game she asks her to play, involves the re-creation of a series of reclining nude images. In an interview with Dennis Bartok, Varda speaks of letting Birkin come into her world, a world of paintings by Titian and Goya, of the Renaissance poems of Louise Labé.[14] She says she loves the paintings so much. Her play with these works with Birkin is indulgent, luxurious, and affectionate. It is a pursuit of love. She says Birkin looks so beautiful in these images.

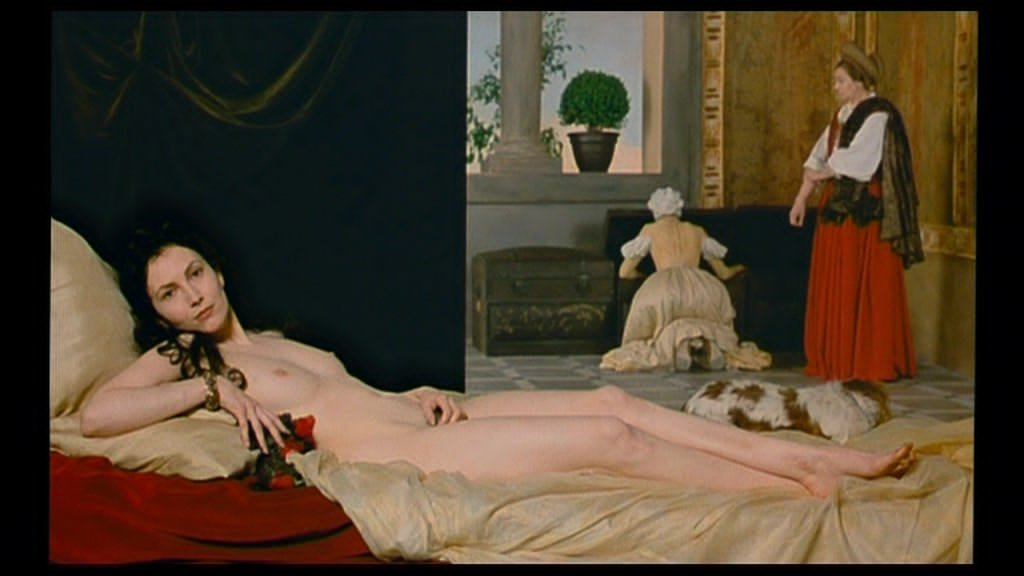

The film opens with a tableau vivant whose coordinates are rearranged. Varda takes the setting and furnishings of Titian’s Venus of Urbino. This honeyed image is her reference, but in recreating in cinema the scenario of the painting, she opens it to a hive of further art historical references. She alludes to the Ecole de Fontainebleau, notably La Dame à sa toilette [Lady at her dressing table] (1560), and lavishly references paintings of reclining women by Goya, placing Goya’s nude on Titian’s couch. The Titian tableau vivant offers a set in which different reclining nudes may be re-staged and reimagined.

In the opening scene Birkin is dressed in yellow. The dress identifies her with the servant seen looking into a coffer in the background of Titian’s painting. In Varda’s reconstruction, Birkin is seated on a chair in front of the coffer. The details of the setting are correct, with the same column and plants at the window behind, the same patterns of light, the same drapes. But Varda has added a naked woman with a yellow flower on the left and a reproduction of La Dame à sa toilette on the right (though the image postdates the Titian). The setting is used as a space for Birkin to speak about her thirtieth birthday.

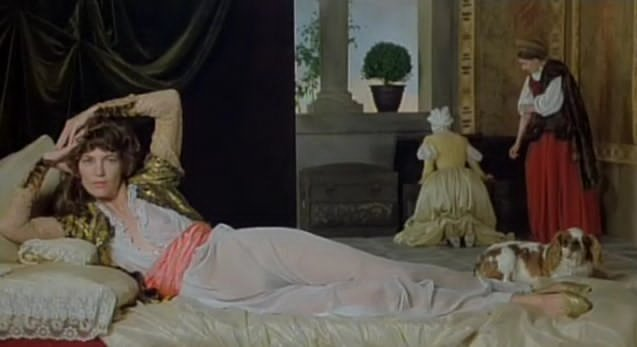

Varda creates her filmic portrait of Birkin with a nod to pictorial tradition. Announcing a further reclining sequence she says: «et si on commençait par un portrait officiel à l’ancienne à la Titian, à la Goya’ [let’s start with a traditional portrait à la Titian, à la Goya]». She leaves unremarked the fact that she will offer a portrait form that alludes not to portraiture but to the reclining nude. The film cuts to a further tableau vivant. Birkin is wearing a Goya-style robe with a gold gilet, a salmon-pink sash and gold shoes. The fabric of her shift is so thin her nipples and thick pubic hair can be seen through it. She is still in the scene, on a Titian-style stage with a little spaniel sharing her couch. The image references Goya’s La Maja Vestida (1800-1805) though the pose is inverted. The film cuts again only fifteen seconds later to Birkin naked, but still resembling a Goya painting, now the La Maja Desnuda (1797-1800).

Birkin is a Goya beauty rather than a Titian: lean, dark-haired, pallid. She is noticeably thinner than Goya’s model, her body stretched like a dancer’s. Her delicate skin is loose in places, structures of her bones and joints showing. She is ethereal, yet, more than the Goya, present, centred, absorbed, not coquettish. Her body is stretched out in an arabesque, unabashed, basking, and it is skinny, labile. This image yields to mesmerising footage of Birkin, naked. Beyond the playfulness and staginess of the tableaux vivants, these shots are Varda’s most imaginative cinematic apprehension of Birkin as reclining nude.

Here there are shots of a different scale from any others in the film, intimate images of Birkin, naked, reclining. There is a blur of sheet and then suddenly large-scale toes as the camera prepares to pass close to its subject in a pan which travels from right to left up the line of Birkin’s body. The camera is languid in its moves along the body and the take is continuous. The camera approaches the sensitive flesh of Birkin’s nipple, then the almost imperceptible curve of her breast and her soft face, pearly, blushing, with her glossed lips drawing out the colour of her nipple. The sequence rests on Birkin’s eyes looking back. Her gaze reveals that she is present in the image, responsive, calm. She has let this shot be achieved. She is immobile. She has submitted to the slow sweep of the camera that feels at its close a form of ravishment. The audacity of what is done is tempered by the extraordinary simplicity, intimacy, and tenderness. As part of her portrait of Birkin, Varda reimagines the reclining nude closely showing Birkin’s naked, pale, living body.

Varda finds a different apprehension of the body of a living other. Her attention renders her approach to a figure from pictorial art newly mobile, sensory, dimensional. As Birkin’s body is followed with a background of sheets, white material, the difference between animate and inanimate matter is marked here, heightening a sense of skin and flesh as feeling, as vulnerable. In that vulnerability, the exposure to the gaze, the incarnation, the yielding, the curves and folds show eroticism. The body of the other as impressionable, sexy, is unexpectedly revealed. The film captures the hush, the trust, the tremulousness, glistening, taut, of being naked, of being bare before the camera and surveyed and filmed. The camerawoman is close enough to sense emotion, response, feeling. Complicity and tenderness are needed for these shots to be achieved.

Varda’s cinematographer on Jane B. par Agnès V., as on Documenteur, was Nurith Aviv. Aviv first worked with Varda on Daguerréotypes in 1975 and in that year Varda spoke in interview with Mireille Amiel about ways of approaching subjects in documentary: «the thing is, that if you’re going to approach someone, you must do it gently. Slowly in physical terms and slowly in moral terms as well».[15] She continues: «I have a lot of admiration for Nurith Aviv’s camera work: her images affirm her deep respect for her subjects».[16]

Aviv’s work with Birkin is gentle, the slowness of the pan gesturing to affective attention and care, the shots yielded intimate and protective. This gentleness also involves eroticism and response to Birkin’s body as sexual, as desirable, as adorable. This is the gaze that Aviv’s camera allows and that Varda’s film encompasses as part of its response to Birkin’s beauty and her vulnerability.

The reclining nude shots of Birkin, pursuing the visual experimentation of the mirror images in Documenteur, allow Varda to approach a sensual, tactile, prehensile, and expressly horizontal, non-vertical reckoning with female eroticism. In the 1975 interview with Mireille Amiel she offers a vision of the body that is responsive across its whole surface, its length and depth: «for me, to be a woman is first of all to have the body of a woman. A body which isn’t cut up into a bunch of more or less exciting pieces, a body which isn’t limited to the so-called erogenous zones (as classified by men), a body of refined zones…».[17] She continues: «all you have to do is imagine a woman who likes to be caressed under her arms and who says so only to have her lover complain that he’s not her physical therapist! Our women’s voluptuousness, our desire must be reclaimed!».[18]

The shots of Birkin moving across her body do not fetishize or organize the parts they glimpse. These images of Birkin revel in her sensuous loveliness, attending to her voluptuousness. As they pass over her surface they are pearly, limpid, ecstatic in their sensing of her skin and its stretch and pliability. Yve-Alain Bois and Rosalind Krauss have drawn attention to «the vision of animals focused on the horizontal ground on which they and their prey both travel, a vision that is therefore, in certain ways, merely an extension of the sense of touch».[19] They continue, through Freud, to see that «[t]he imbrication of animal vision not only with touch but even more with smell, intimately tied seeing and sexuality».[20] In Varda horizontality is used to realize a different relation to touch and proximity in a remapping of female pleasure that envisages the possibility of the full stretch of Birkin’s body offering different sensations, and polymorphous pleasures, and which also remains with inscrutability, not anticipating control of what she likes or what she feels.

Voluptuousness, eroticism, are held in Varda’s gift to Birkin of these skin images, a grafting, a reminder of her loveliness, a promise that she is all this and that her body, at this moment of perfection and vulnerability, exists, and will also be remembered, cherished, held on celluloid. If Varda lets a timeless pose, the reclining nude, survive in her imaging of Birkin, it is to know that image, and Birkin’s image, anew, and also to hold her body, to spread it out for pleasure, ravishing, whole. With these shots, Varda writes a different history of pleasure and erotic imaging for Birkin and envisages a different apprehension of the reclining nude. This gift to Birkin seems especially poignant at this moment in her life, and marked in relation to the more pornographic sexual imaging of Birkin to which the film also refers.

In Varda par Agnès, Birkin is quoted in interview: «etre un modèle pour un artiste, j’ai toujours adoré ça. Mon père faisait de la peinture, et quand j’étais jeune, je pouvais rester des journées entières à poser pour lui [I’ve always loved being an artist’s model. My father painted, and when I was young I could spend whole days posing for him]».[21] Her narrative of her life as model and actress goes back to childhood and her relation to her father. Varda goes back to Birkin’s childhood, blowing up images of a little girl as she explores her childlike persona. In an interceding scene where Birkin plays an art dealer, her artist describes her as «une petite fille déguisée en femme fatale [a girl disguised as a man-eater]». Nostalgia for childhood is referenced in the film later in snow scenes where Birkin wears a swan’s down hat and the colours of the shot are blanched sepia. Birkin speaks of «la rêverie, le silence, l’enfance aussi [a dream world, silence, and childhood]». She speaks about fairy tales, Snow White and Beauty and the Beast that her mother read to her as a child and that she reads to her children. Birkin later tells Varda a story of a film she would like to make, her fantasy, of the love between a woman and a young boy. Varda tells her that she is really thinking about her own childhood and about the pain of leaving childhood behind.[22] The scenarios of the film can seem at times like a series of dressing up games with Birkin as an overgrown child.

In the slideshow Varda shows an image of Birkin’s face and shoulders, illuminated, with behind her a shadowy black and white photograph of her childhood self with her siblings. The little girl Birkin is seen on the right of the frame looking towards her adult self. The child’s posture is correct, her hair combed, her body clothed in a dark high-necked sweater. Birkin says: «j’étais un enfant sage [I was a good child]». She says she wanted to be like her brother Andrew, her words directing the viewer round the frame to see him, and then to see her girlish sister. Birkin has her siblings and her child self around her like a halo. She speaks with the photos blown up to life-size behind her but she looks at the camera, as if she can also see them in her mind’s eye. There are the sounds of a slide projector as another photo appears. Birkin is in a party frock and holds a posy of flowers.

As the slideshow continues Birkin is lost from the frame and there is a family picture, a schoolgirl image of Birkin with spaniels,[23] boarding school photographs in faded colours. Birkin speaks about her unhappiness and her passion for another girl at school, Jane Welpley. Varda uses the domestic set-up of the slideshow to hold Birkin’s memories. Images from Birkin’s childhood close in on Birkin’s vulnerability, her accessibility. Crawford writes in Attachments, «photographier Jane est comparable à photographier un enfant [photographing Jane is like photographing a child]».[24] This image of Birkin as ingenuous and in need of protection, like a child, exists in Varda’s film alongside images of Birkin as nymphet, as nude. These shuffled images are all part of an affective history of Birkin’s bareness, her nudity, her availability to be fashioned. Part of this slideshow of earlier moments in Birkin’s life, and interspersed with pictures of Birkin and her tiny daughters, of Birkin and Gainsbourg in family snapshots, the pin-up images reveal her eroticism, her professionalism, alongside her naturalness, her intimacy, all part of the stretch of her life.

The slideshow moves on to Birkin’s first film role in The Knack…and how to get it (Richard Lester, 1965), to her role as a nymphet in Blow-Up. There is a blanched still of Birkin, fragile, bare to the waist, with long fringe and hair, her lips open as David Hemmings wrests a dress from her. She is seen in a colour film still with Gainsbourg and then dining with him in a black and white photo. He smokes a cigarette. Her long hair is sleek as she glances at him. The restaurant is decorated with frescoes of an Arabian palace, a fairy tale setting. In a closer image of the couple Gainsbourg’s arm is draped across Birkin reaching to clasp her as he stands behind her. His bare forearm is round her, his face close enough behind her for her to feel his breath, for her hair to brush his lips. His face is half covered by hers in front. In an impromptu backstage photo they are seen practicing together, Birkin elated, her face doubled in a reflection in the piano. The photographs are small documents of their love for each other. These are a few glancing images, affective pieces, stills from a passed world.

The film pauses twice over an image of Birkin in a silver suit, her hair long in curled tresses, her pink lips against the denim of Gainsbourg’s crotch. Her face is there on the material as she is between his legs looking up at him. The first time the image is shown Varda crops it so that Birkin is in the frame, and Gainsbourg just from waist down. This editing shifts focus to her. With her head inclined, her hair falling, she resembles one of the prone faces of Dalí’s The Phenomenon of Ecstasy. Her skin is unreally pale. Her silvery dress, the folds of the fabric and curls in her hair make of her a sexual Ninfa. She looks at Gainsbourg with ardour, her eyes almost surreal as the pupils roll back. Her face between his legs, her lowered pose, create a disorganization of the image, an imbalance that is erotic. The closeness of her face to the denim between his legs leaves tactile impressions. The detail Varda shows is blurry, the colours and edges softened. It feels as if the showing of this image works to hint at some of Birkin’s feelings in this shot, the framing getting closer to her perspective and viewpoint.

The full image appears further on and it is reversed. Full length the image gives attention to the reciprocity of the gaze between Gainsbourg and Birkin as she looks up from her pose on the floor. The sureness of his stance, the elegance of her silver shining shin, her high heels, make the image more iconic, more glitzy. In her play with the image Varda crosses between and correlates this public provocation and hidden feelings. In conversation with Miranda July, she says about Birkin:

What I love about how her mind works is that she never erased things that had happened in her life, no matter what happened. And I loved the idea that she said at some point that whatever Gainsbourg asked her to do, whatever it was, stupid things like being locked to a radiator or something else… okay, that was the time she did that. She would never say: “that was stupid and that I shouldn’t have done that”. She told many stories just like this and had no regrets.[25]

Varda shows these foolish things. These images are part of her archive of Birkin. They are images she chooses and asks Birkin to contemplate, to look at now. They are part of her visual collage adding something still more lurid, surreal, varied, to the film. The imagery recalls Varda’s invocation of a plasticine Eve as Birkin is seen in a fetish suit and conical heels with a fire bucket and fire hydrant, her hair dizzily bunched to one side. In a further image she is seen in the sheerest stockings and gold and black fragile sandals, draped, posing, across a velvet chair. If the idiom of these images speaks of porn, the centre-fold, their details return in family photos Varda also includes, showing Birkin with her tiny daughters, her bare back crossed by the thin straps of a bathing suit. Gestures, her smile, her elated feelings return across the spread of images.

The image of Birkin padlocked to a radiator appears in the film as a serial and varying image, as Varda films the plates in Gérard Lenne’s 1998 book on Birkin. These bondage images were for a Christmas issue of «Lui» magazine. The plates show three small images of Birkin in high heels and stockings on a metal frame bed. She lies on her front and her body is contorted, in hand cuffs. The turns in the image recall hysteria. Her hair hangs down and she seems to move naturally across the shots, as if these are motion studies. The fourth image, crossing over two pages, the glossiest and most composed, shows Birkin kneeling on the floor and locked by one handcuff to the radiator. Her buttocks are on show, modeled flesh delineated by the black elastic of her suspender, her hair in strands all down her back. She is almost nestled against the radiator, her arm relaxed in the cuff as if it is a metal hand holding hers. She is childlike, despite the carnal, raw, inert presence of her hips and thighs. She says to Varda: «J’étais si contente que Serge soit fier de moi [I was so happy that Serge was proud of me]».

Birkin’s happiness is Varda’s focus across this bizarre range of images: her happiness as Gainsbourg’s lover, her happiness as a sex object and model meeting his desire, her happiness as a mother, as a young woman. In a double portrait with Gainsbourg, he holds Charlotte and Birkin holds her oldest daughter Kate in a towel on her lap. She is drying her after the bath and her head is on one side. She is smiling, enclosing her damp child in her arms. The slideshow explores with due delicacy the involvement of Birkin’s desire to be loved, to be beautiful, with an expanded narrative of family happiness, of tenderness, sensuousness, intimacy. Varda says of Gainsbourg and Birkin in her interview with July: «and they were an incredible couple, so different, so strange».[26]

Varda’s film makes visible a passion, a need to be loved, on Birkin’s part. She shows what this lets Birkin consent to. She shows need, response, co-dependence, with clarity, combining a measure of indulgence with critique, care and curiosity, a liberal acknowledgement of the queerness and inscrutability of all attachments, including Varda’s own to Birkin in this film.

These issues are caught up in a rehearsal scene between Gainsbourg and Birkin filmed by Varda. For Richard Brody this is «the film’s most tender sequence’ showing ‘Serge Gainsbourg carefully coaching Birkin through one of his songs’».[27] The scene is prefaced by a shot of the scribbled pencil manuscript of the song, like a Cy Twombly painting of the wilder shores of love. Gainsbourg standing behind Birkin as she sings directs her, his hands moving. His presence is tender, yet also rough as he rights the sounds of her French, as he teaches her where to breathe, as he forcibly brings her closer to the mike, and directs her with his hand on the back of her neck. He wants a kiss at the close. Her smile is untroubled, radiant, and the song, rehearsed, is lovely, its rhythms bringing his body and hers, their voices, their gestures into some alignment. In the middle of the song Varda cuts to an image of Birkin practising at home in her dressing room full of flowers, abundant lush orchids. She is in luxury. Yet she is also roughed up in this sequence, corrected, disciplined in her singing by her past lover, childishly inept as her English accent upsets the sounds of the song. Varda comes closest to showing Birkin’s gaucheness in shots of Birkin performing where a technician needs to move her into the spotlight.

For Birkin’s fortieth birthday, Varda literally wraps up her house up like a gift with pink ribbon. The film moves into the interior of the house, a documentary of the interior. Birkin speaks of baby photos, of her mother as a baby, of herself, of her children, and the images are seen lining the stairs. Their images are glimpsed later as Birkin talks of her fantasy with a young boy. Domestic images and erotic fantasy illustrate each other. There are white flowers Birkin has received, Madonna lilies on long stalks, in cellophane and ribbons embalmed as if under glass. Taxidermy creatures live in her house, further reminders of time passing, mortality, and agelessness. She has a Victorian mahogany bathroom with bottles of English lotion tied with laces. These spaces are the depths of the story, deeply in Birkin’s domestic life, in her daydreams.

Varda asks Birkin if she dreams. The forms of Birkin’s dreams then offer so many small surreal pieces in the kaleidoscope narrative. Varda says that she finds Birkin offering herself to the imagination. She speaks about lability, malleability, about how this is what in Birkin inspires her. She talks about the ways in which she can use Birkin in her imagining, how she can dress her up, model her.

Varda offers a staged image of Birkin as muse reclining, dreaming or daydreaming in sand, half-submerged. She is crowned with leaves and pensive. Her dreaming face, staring into the distance, seems to call up a sequence of still frames of paintings, Arcimbaldo’s kaleidoscopic Rudolf II (1590-1), Paul Delvaux’s La Visite [A Visit] (1939) and a scene from Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights (1503-1515). Varda allows the reproduced paintings to exist as figments of Birkin’s imagination, her dream world. She runs from a composite portrait where leaves, fruits and blades of corn have consumed an entire face recomposing it, through a Surrealist image of a woman holding her breasts as a child enters the room, to the enlaced and enchanted lovers, pale, cavorting, the strange-scaled fruits, the butterflies, in Bosch’s paradise. There is an elastic, associative relation between the paintings and the returning preoccupations of the film. Painting here offers an intersubjective space of imagining that Birkin makes possible for Varda, and Varda projects as Birkin’s unconscious.

In this Vanitas film, Varda buries Birkin in leaves and in sand and burns her as Joan of Arc. As she muses on Birkin’s ambivalence about fame and glamour, her desire to be both unknown and famous, she begins to talk about the death mask of ‘l’inconnue de la Seine’ [‘the unknown woman of the Seine’] and of her enigmatic smile. The image of the corpse of Mona, the unknown woman Varda brings back to life for the short time of Sans toit ni loi (1985) is never far from Jane B. par Agnès V. Making Birkin a sister of Emilie in Documenteur (1981), Varda returns too to the myth of Ariadne. She shows Birkin as Ariadne, daughter of Minos, in the labyrinth, her own camera with its gaping viewfinder the pursuing minotaur. She says that she sees Birkin like Ariadne sleeping on the beach abandoned by Theseus. Her film responds to Birkin’s capacity for abandonment, for giving herself up, leaving her like Lol in Duras’s novel: «elle dormait dans le champ de seigle, fatiguée, fatiguée par notre voyage [she was sleeping in the field of rye, tired, tired by our journey]».[28]

Birkin gives herself over to Varda for this film. She lets her story be told and in the end looks into the camera with disingenuous charm. The film reflects on how to be a model is to be intoxicated with this giving over, with a childlike malleability, and even an inert, doll-like vacancy. It shows Birkin’s vulnerability, her impressionability, her openness to Gainsbourg, to sexual exposure. It opens itself as film to these relations, showing their truth, their foolishness, but not dissolving or dismissing their power. This is a bid rather to understand pleasure that women might take, to encompass variations in female subjectivity, interiority and desire. If she critiques Gainsbourg, Varda also shows herself choreographing and correcting Birkin. She shows the complicity, co-dependence, sadism, and love, of relations between artists and models. The film feels like an experiment where Varda puts herself at risk where she also works to reassure Birkin. It is a project where she achieves a new, beautiful filmic engagement with the reclining nude in her slow pan over Birkin’s body. She lets the viewer reflect at length on her love of the reclining nude, her sensitivity to these suave images of repose that return in her films, these images that speak of indolence, pleasure, death, and commemoration.

Birkin tells one childhood memory of being at the beach and finding a newspaper that reported the death of Marilyn Monroe. She speaks of Monroe as «inspiratrice naïve’ [naïve muse]», and she tells her dreams of wanting to move like her. What they have in common, she says, is held in the song My Heart Belongs to Daddy. She whispers the lyrics in English and in French. A late scene in the film is set in the casino at Knokke le Zoute with its Magritte frescoes, with Birkin as croupier and Varda as gambler. In a slow pan from right to left (the direction of the pan along Birkin’s body), Varda’s camera moves across the images on the wall, their surrealist dissolving world, the blue breasts of a naked woman. Music composed by Joanna Bruzdowicz for violin, flute and saxophone accompanies the image. The casino is where Varda’s father died. This sequence seems to exist in the film, unspoken, as a small elegy for this man, the pan, as with Birkin, a movement in time, in memory, a caress, a visual survey, an expanse of emotion.

Carol Ann Duffy, in a love poem, writes: «next to my own skin, her pearls. / My mistress bids me wear them, warm them, until evening». The pearls require the warmth, the humidity of living flesh to shine at their most beautiful. The maidservant wears the pearls so that they will glow, and not sit on skin cold to the touch. The necklace, slack, a rope, renders sensory the exchange between the women: «she’s beautiful. I dream about her». The pearls are used to find a form for the epidermal contact between the two women, their sensual closeness, the animal sensing.

In a late return to the Titian tableau vivant, Birkin plays the servant again and dresses up in her mistress’s white dress and iridescent pearls. In a discussion of Titian, with her father John Berger, Katya Berger writes: «jewels remind us, don’t they, of the pleasure we’ll lose when we’re dead, and how they and their precious stones will still be here? They console a body for its vulnerability».[29] In these borrowed clothes Birkin reads lines from a poem by Louise Labé.[30] The episode with the pearls leads to a last reclining nude image where the mistress herself (Pascale Torsat) lies out naked on Titian’s sofa, a living double of Birkin, as she lets red roses fall from her fingers. Birkin as Pandora at her coffer lets out flies that settle on the image of the naked woman. If these are the flies of the Italian summer countryside, they also make the mistress an image of death in life, of mortal flesh, of incipient rot. If pearls console us for the frailty of the flesh, the flies still gather.[31]

* All the images accompanying the paper are frames of the films mentioned in the text. Title and year are reported in the captions. Thanks to Ciné-Tamaris for the kind permission to reproduce the images.

1 She uses the formulation «film kaléidoscope» (A. Varda, Varda par Agnès, Paris, Cahiers du cinéma et Ciné-Tamaris, 1994, p. 184). Translations from texts are mine here; translations of film dialogue are taken from the Ciné-Tamaris DVD editions.

2 A. Varda, Varda par Agnès, p. 184.

3 Ibidem.

4 From the introduction ‘Agnès présente le film’ on the Arte/Ciné-Tamaris edition of Jane B. par Agnès V.

5 Ibidem.

6 A. Varda, Varda par Agnès, p. 184.

7 S. Flitterman-Lewis, To Desire Differently: Feminism and the French Cinema [expanded edition, New York, Columbia University Press, 1996, p. 354.

8 M. Rosello, ‘Agnès Varda’s Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse: Portrait of the Artist as an Old Lady’, Studies in French Cinema, vol. 1, n. 1, 2001, pp. 29-36: 35.

9 Varda’s film can be seen in two senses as a vanitas film and as a film about vanity. Borzello describes «the type of still life known as the vanitas, an arrangement of objects that illustrate the transitory nature of the pleasures of life and she notes: «[f]emale beauty has traditionally embodied the idea of a short and poignant flowering before a fading» (F. Borzello, Seeing Ourselves: Women’s Self-Portraits, London, Thames and Hudson, 2016, p. 69). She makes a connection elsewhere between female self-portraiture and vanity: «the idea of the female affinity for self-portraiture may have drawn strength from the personification of the vice of vanity, and is in fact a subtle insult. Since vanity was for centuries personified as a woman looking in a mirror, a female self-portrait is evidence of this female vice» (Ivi, pp. 28-30).

10 A. Cavarero, Relating Narratives: Storytelling and Selfhood, London and New York, Routledge, 2000, p. 56.

11 Ibidem.

12 These words are heard as the film shows a montage of magazine covers of Birkin including cinema journals, «Paris Match», «Elle» with a feature on her smile, and a knitting magazine which shows Birkin in angora.

13 Varda echoes the phrase «la rencontre fortuite sur une table de dissection d’une machine à coudre et d’un parapluie [the chance meeting on a dissection table of a sewing machine and an umbrella]» (I. Ducasse, Comte de Lautréamont, Oeuvres completes. Les Chants de Maldoror. Lettres. Poésies I et II [1869], Paris, Gallimard, 1973, p. 234). The phrase, associated with the Surrealists, occurs in the sixth song of Maldoror and it is the last in a series of similes used to describe the beauty of a sixteen-year old boy, Mervyn, «ce fils de la blonde Angleterre [‘this son of blond England]» (Ivi., p. 234).

14 This interview is included as an extra on the 2015 Cinelicious Blu-Ray disk of Jane B. par Agnès V.

15 T. J. Kline (edited by), Agnès Varda: Interviews, Jackson, University Press of Mississippi, 2014, p. 68.

16 Ibidem.

17 Ivi, p. 74.

18 Ibidem.

19 Y.-A. Bois, R. Krauss, Formless: A User’s Guide, New York, Zone Books, 1997, p. 90.

20 Ivi, p. 91.

21 A. Varda, Varda par Agnès, p. 185.

22 This fantasy was originally to be realized as an episode in Jane B. par Agnès V. but it was developed instead as the full-length companion feature film Kung-Fu Master (1988).

23 Varda has included a rather fidgety spaniel in the Titian tableau vivant earlier in the film.

24 J. Birkin, G. Crawford, Attachments, Paris, Editions de la Martinière, 2014, p. 120.

25 This interview is included as an extra on the 2015 Cinelicious Blu-Ray disk of Jane B. par Agnès V.

26 This interview is included as an extra on the 2015 Cinelicious Blu-Ray disk of Jane B. par Agnès V.

27 R. Brody, ‘Family Affair’, The New Yorker, February 1, 2016, p. 8.

28 M. Duras, Le Ravissement de Lol V. Stein, Paris, Gallimard, 1964, p. 191.

29 K. Berger Andreadakis, J. Berger, Titian: Nymph and Shepherd, London, Bloomsbury, 2003, p. 34.

30 The poem is Labé’s Baise m’encor, rebaise-moi et baise [Kiss me again and again a kiss] and Birkin reads the first two stanzas.

31 This article originally appeared, in a more heavily annotated version, in E. Wilson, The Reclining Nude: Agnès Varda, Catherine Breillat, and Nan Goldin, Liverpool, Liverpool University Press, 2019). This is dedicated, with love, to Ioana. 2020 is the year of Jane Birkin.