In the late 1990s Pinocchio began to appear in Jim Dine’s art – for example, in the 1998 lithograph The Mezzotint Boy – bringing with him memories from the artist’s childhood, and bearing traces of his fascination with the character of the boy-puppet that he first encountered in the 1940 Disney film which he saw when he was six years old. Pinocchio is now established as one of the recurring motifs in Dine’s art, along with hearts, bathrobes, tools, birds and antique statues of Venus. Dine has now produced a series of polychrome, wooden sculptures of Pinocchio exhibited at the Pace Gallery in New York in 2006-2007, a portfolio of some forty prints based on the Pinocchio story exhibited at the New York Public Gallery during the Winter of 2006-2007 and Alan Cristea Gallery in London in Spring 2007, the closely-related illustrations to an edition of Collodi’s original text of Pinocchio published by Steidl in 2007, and even a monumental thirty-foot high bronze figure of Pinocchio for the Swedish town of Boras [fig. 1a]. Since 2012 visitors to the art museum in Dine’s home-town of Cincinnati are now greeted by a twelve-foot high bronze statue of Pinocchio with arms raised to the heavens [fig. 1b].

Things are invested with emotion by Dine, often an emotion associated with childhood: «All these objects come out of my childhood» (Jim Dine in conversation with Germano Celant and Claire Bell, in Celant-Bell, 1999, p. 156). Whether these things are the bathroom fittings sold by his family, or the tinned foods stored in cupboards during the Second World War, Dine’s memories invest them with a personal, even autobiographical quality quite distinct from the fascination with the glamour of commodities and advertising evident in Pop Art. Tools, in particular, are felt by Dine to carry a shared legacy of work in their forms: «A tool can be inspiring […] because this tool is a beautiful object in itself. It has been refined to be an extension of one’s hand, over the centuries, in a process of evolution. And it can inspire you that way» (Celant-Bell, 1999, p. 132). This feeling for objects makes them vehicles for a type of self-portraiture so that, for example, when the bristles of a house-painter’s brush are lengthened to resemble a beard from one state of an etching to another, the brush becomes a portrait of the artist as the legendary Blackbeard. Equally the image of a bathrobe found in a magazine advert becomes a reiterated form of self-likeness in works across different media. Although Pinocchio is a relatively late motif in Dine’s art, he has been present in his practice since his twenties in the form of a cherished object, a commercially produced figure of Pinocchio:

I found a doll of Pinocchio, franchised by Disney at the time of the film. A beautiful doll, with real clothes – I mean cloth clothes – and papier-mâché and hand-painted head, arms, and legs […] it’s in pieces in my house. Because it’s just so beat. I’ve done all kinds of things with it. I’ve cast it, I’ve taken it with me. It’s just completely beat. But it was a beautiful thing (Ackley-Murphy, 2012, p. 134).

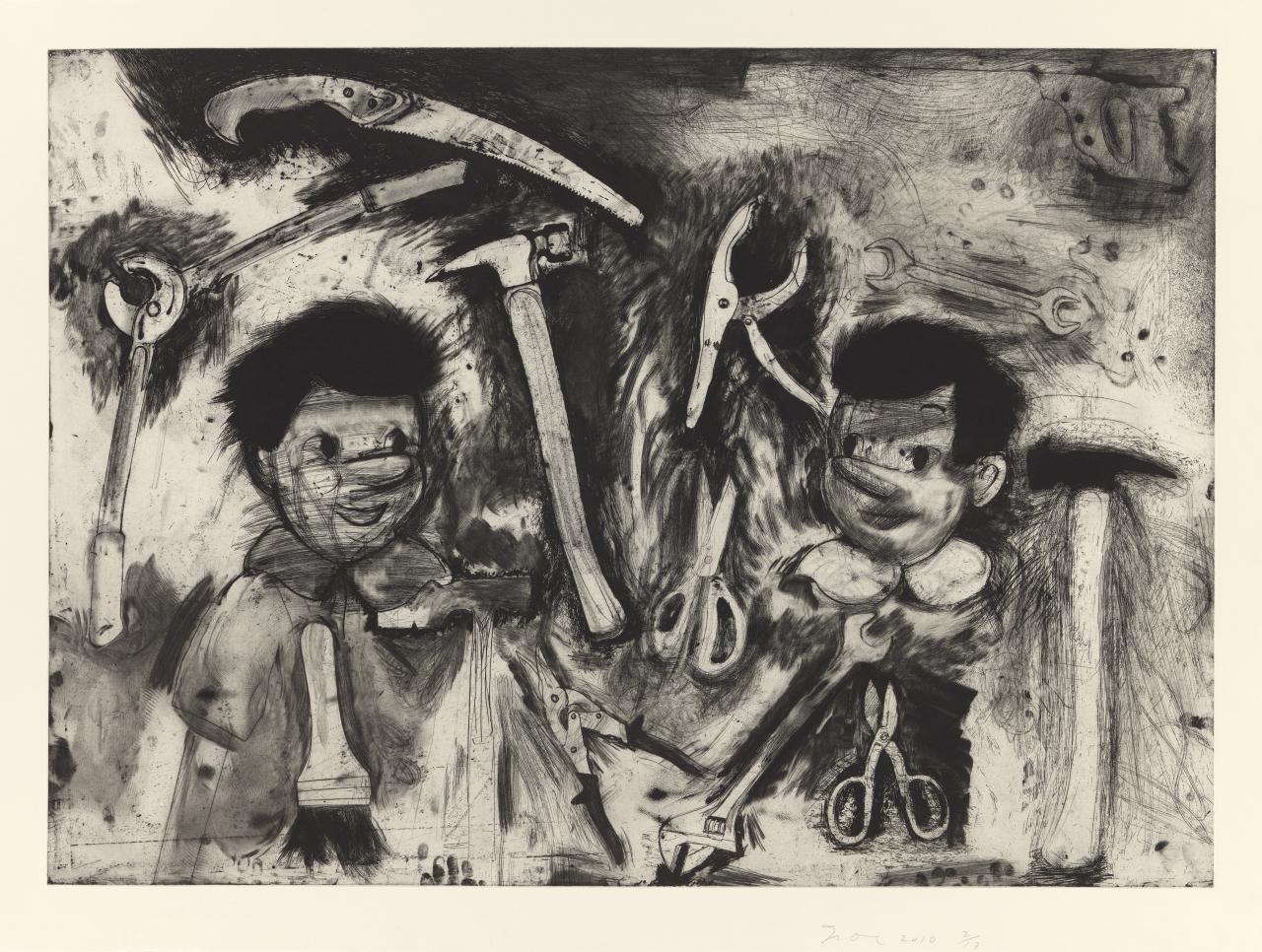

Pinocchio the Disney character perhaps represents for Dine an unconscious creativity whose source is a child’s fascination with things: «I have an access to my childhood that many people are jealous of. I can access childhood very easily. I don’t mean just memory. I mean feeling. And I am very much in the head of the child» (Celant-Bell, 1999, p. 50). Dine’s concern with Pinocchio is not merely illustrative and somewhat oneiric associations connect him with his other obsessive concerns, the face of the puppet appearing among a characteristic range of free-floating tools in the 2010 etching Landscape of Things, for instance [fig. 2]. The Pinocchio of an American childhood is, however, confronted with the text of Collodi as part of the reflective exploration of tradition that characterizes the artist’s mature engagement with European art both modern and antique. The 2006 sculpture The Philosopher [fig. 3] shows Pinocchio contemplating a table loaded with tools, as if pursuing a form of self-analysis in reflecting on his origins, or perhaps even taking the place here of Geppetto the carpenter as the form-giving artist. Revealingly when Dine came to illustrate Geppetto for his edition of Collodi he provided his own self-portrait, demonstrating his own self-identification with both Geppetto and Pinocchio. For Dine, Pinocchio is ultimately a metaphor for God in man, and his transformation from wooden puppet to real boy is akin to an alchemical process (perhaps suggesting the homunculus of Paracelsus, or the older artistic legend of Pygmalion):

Every artist is an alchemist – as I understand the alchemical act. That’s what the story of Pinocchio is about. A talking stick that Geppetto carved into a boy that became alive. That was the part of the story that got to me […]. That’s why I stuck with Pinocchio and kept him in my back pocket (Ruzicka, 2002, p. 66).

Bibliography

C. S. Ackley, P. Murphy, Jim Dine Printmaker: Leaving My Tracks, Boston, MFA Publications, 2012.

G. Celant, C. Bell, Jim Dine: Walking Memory 1959-1969, New York, Guggenheim Museum Publications, 1999.

J. Ruzicka, ‘“to invent what you are”: Jim Dine and Printmaking’, Art on Paper, 6, 5, 2002, pp. 62-69.