1. An overview of Elaine Shemilt’s early video artworks

Elaine Shemilt is a world renowned print maker. Her works, including her prints and engravings, have been shown internationally and documented in exhibition catalogues and books.[1]

Nonetheless, little is known about her experimentation and work in the realm of artist’s video and film of the Seventies and early Eighties. This is partially due to the fact that the artist destroyed her video and film works before moving to Scotland in 1984 but it can be seen as part of a more general marginalization of the work of women in the history of artists’ video.[2]

The analysis contained in this article is supported by a literary review of existing critical writings, and artists’ documents and interviews collected during the AHRC funded research project ‘EWVA European Women’s Video Art from the 70s and 80s’.[3]

At the time, several women artists perceived video «as an obvious medium with which to dismantle stereotypical representation and assert the political, psychic and aesthetic evolution of women’s newly raised consciousness».[4]

Commenting on this feminist approach to video, Shemilt explains that «video offered the possibility of addressing new scales and contexts at a time when artists were recognising social change and they were also trying to break down barriers within the disciplines of making art e.g. sculpture and painting».[5]

The videotape, as a low tech technology, could be seen as part of what has been described by Gianni Romano as women artists’ experimentation with low tech apparatus, as opposed to the high tech one (such as 16mm) that «produces constrictive dynamics of representation that many women artists try to subvert»[6].

In particular Shemilt explains, in her practice, that «grainy grey quality of video reflected well in the kind of prints I was making. I wanted something that was low tech (similar to the prints that were created on not very expensive paper). I wanted to convey a newspaper effect or in the case of the videos – a newsreel effect».[7]

Furthermore, video allowed for an intimacy and simplicity: the artist could videotape their performances in a private space, without having to actually face an audience. This was important in those days when women were often breaking new ground. They were usually demonstrating their need to be treated with respect both as women and as serious artists.

Video did not require a large crew (usually necessary when shooting celluloid film).

The technical ease of using the Sony video portapak allowed women artists to retain autonomy over the craft of making their art works. Those women who wanted to record performances that included their own nudity to demonstrate personal and sensitive issues were also freed up to do so in the privacy of a studio, either alone or with only one other person.

Shemilt began to use video in 1974 as a student at Winchester College of Art, with a Sony Rover Portapak. Before that, she had already been using 35 mm black and white photography to record and document her performances and installations.

Unfortunately, before 1984, when Shemilt moved from England to Scotland, the artist destroyed the masters – and only existing copies – of her Seventies video artworks. Today the photographs, drawings and prints remain as traces of them.

In fact, Shemilt considered those video as «artefacts» and «to be a part of the rest of the installation, which of course I dismantled after the exhibition or event and eventually destroyed» as the installation was intended to be «temporary».[8]

The artist considered the derived prints and engravings as the final artwork.

When questioned about the possible influences on this process, and in particular regarding Lucy Lippard’s famous Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972,[9] she explains that that came only later for her and she perceived it as a confirmation of her approach.[10]

Another reason that led the artist to discard her videotapes was the aggressive opposition by male critics she had to face that led her to consider her early video work to be not as valuable as documentation shows it was.

On the relative loss of women’s video artworks, Stephen Partridge has also noted: «male video-artists were cautious about discarding elements or fragments of their works. Most women artists stayed rigidly true to their principles and the works have become lost – “without a trace”». Partridge continues: «The catalogue from the earliest exhibition, The Video Show at the Serpentine in 1975 is revealing. On her catalogue page the filmmaker Lis Rhodes describes a film/video work which was made up of two seven minute companion works, respectively a 16mm film and a videotape which were related through a synthesis of the optical sound track. Similarly Susan Hiller, Elaine Shemilt and Alexandra Meigh also describe a number of works, long since lost».[11]

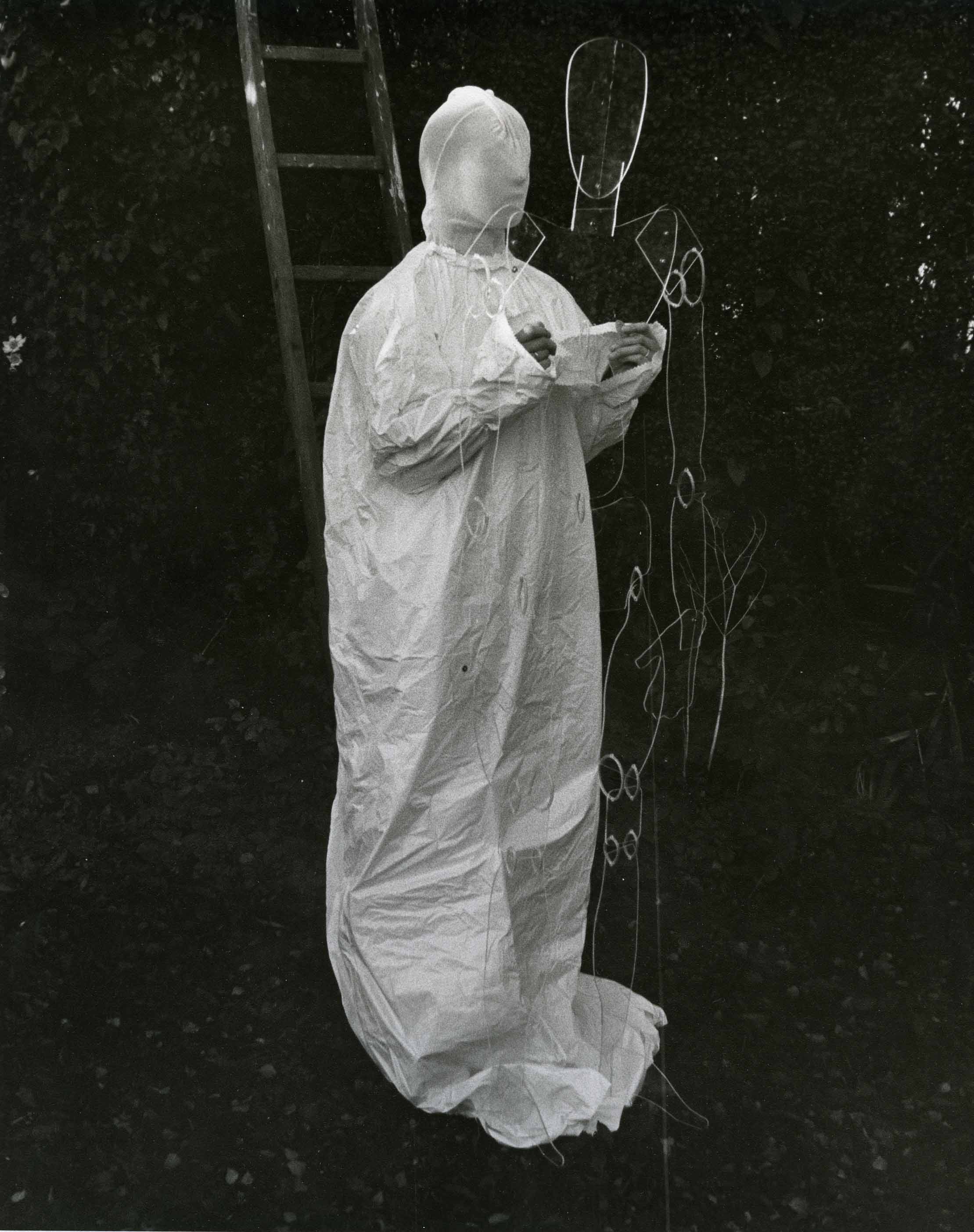

Shemilt has described her first video iamdead (1974) as «an expression of personal insight into the influence of death».[12] Photographs, taken during the videoing of the performance, exist as remaining documentation from this videotape. Prints derived from this video performance circulated and were showed as autonomous works. From Shemilt’s description and these images, it is clear that the video was divided in two performative sequences: the first shot in her home garden, with Shemilt in a gown and shrouded in a veil, manipulating a Perspex human figure within an installation composed by several elements including a ladder and a stool; the second was a performance by the artist, naked, shot in the house cellar.

The work was a re-elaboration of her personal experience of being raised in Belfast during a period of violence and terror. In 1971 she had left her home in Northern Ireland and moved to England but three years after that her grandmother had died leaving her bereft.

Talking about the piece, she explains «I performed in front of the camera, but as an anonymous figure» and details:

I tried to abstract my feelings into something that at the time I described as «script – movement» i.e. a series of movements, which could be interpreted as statements. The question I posed was whether or not death led to absolute nothingness. The video was intended to highlight the confusion between life and death.[13]

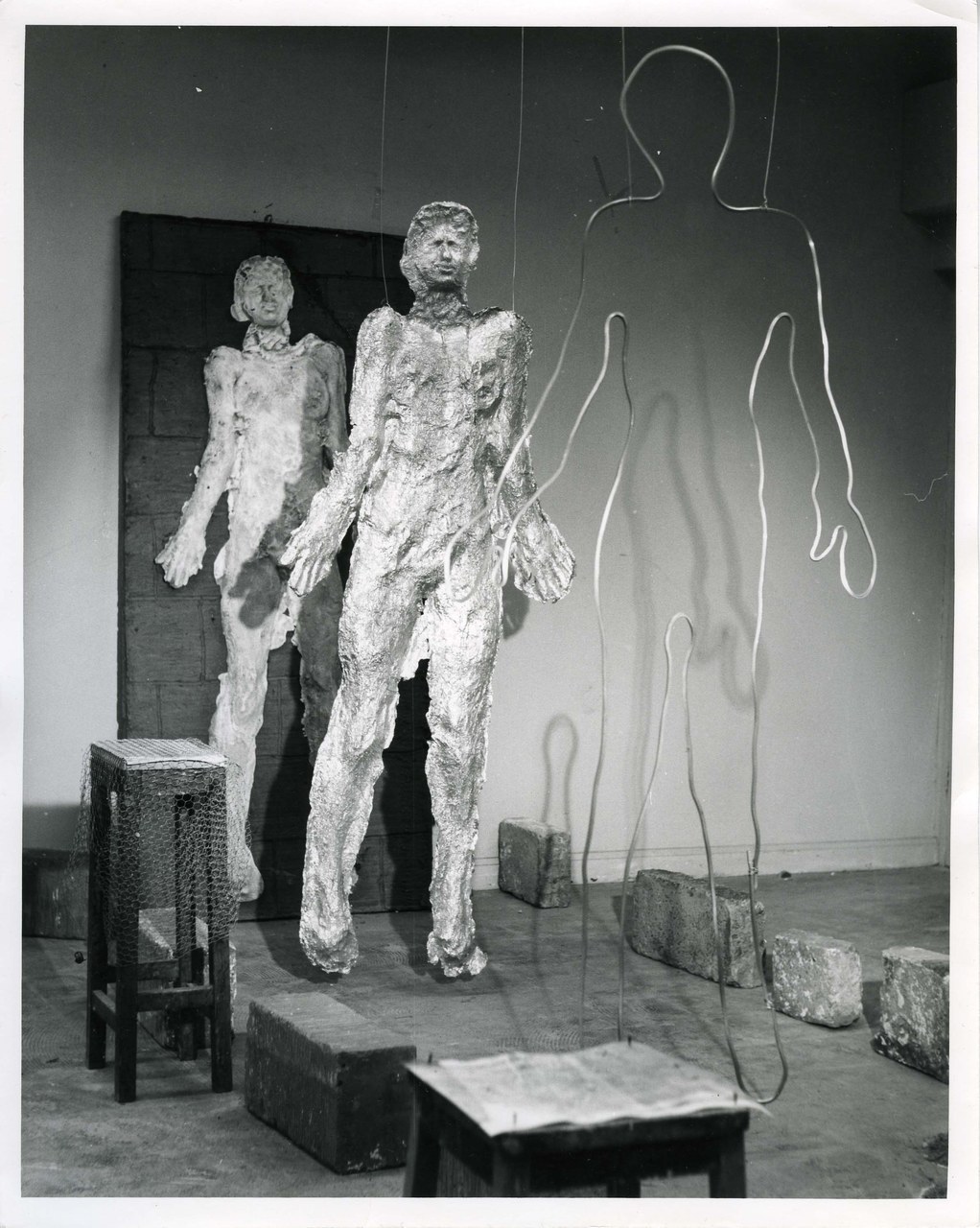

In Spring 1975, she made two videos: Conflict and Emotive Progression, both destroyed before 1984. Conflict was shot in an empty studio at Winchester School of Art, where the artist built an installation composed of various elements including an armature wire, a plaster cast made from a body print in the sand, drawings and sand on the floor, wall and bricks. In the video she made a performance in the installation.

Photographs document the video. Shemilt created also a series of drawings and prints (lithographs and etchings) from it. Conflict, together with Emotive Progression and iamdead, was featured at The Video Show, a seminal independent video festival held at Serpentine Gallery, London, from the 1st to the 25th May 1975. The Video Show included some of the most relevant video pioneers from all over the world including British artists Ian Breakwell, David Critchley, David Hall, Susan Hiller, Brian Hoey, Tamara Krikorian, Mike Leggett, Stephen Partridge, Lis Rhodes and Tony Sinden.

Referring to her notes for The Video Show Shemilt explains Conflict as such:

This film [video] was made in an effort to illustrate briefly the parody of life as a series of conflicts. For example the initial conflict between innocence and social convention as seen in the confusion of a child. Thus the film [video] is in two movements as it were. In the first a figure dressed in white to symbolize life, moves through and explores a series of structures and objects. In the second movement the figure is replaced by a figure in black who wanders back through the wreckage of the structures. As death she controls life until they unite into nothingness.[14]

Emotive Progression, destroyed by Shemilt in 1984, also was shot at the Winchester School of Art. Today photographs document it. As final artwork, Shemilt derived a series of drawings and prints from it. The video was shot in two sequences. In the preparatory phase to the video, Shemilt built an installation with standing screens made of tin foil and paper. Then with the camera in her arms, she walked thorough these screens and then filmed the after effect. In this case the artist is performing simultaneously while making the video: the video/performance is the result of her actions with the camera.

The second sequence documented another installation with a wire human shaped sculpture.

In the notes for The Video Show, Shemilt points out that «The final effect is primarily intended to be an aspect of my sculpture but in such a way that involves movement and sound». The video allows the artist to give a performative quality to her sculptures.

As mentioned before video was part of a more complex installation/sculpture and as part of it was later destroyed. Its ephemeral quality was that of the installation itself.

Shemilt recalls visiting The Video Show with the enthusiasm of being part of the experimentation with the new medium but it left her with sense of isolation, of not being part of that «video community». As she explains:

I remember wandering around and thinking that in this exhibition my videos were well crafted and contained interesting imagery, but wondering whether my particular use of video was appropriate in this sort of context. I certainly left and went back to Winchester feeling rather isolated rather than being a part of a movement. I think this may also be why I didn’t place too much value on the video works without the installation.

So after this experience, she focused her practice more on the prints and photography even though she continued to use video as part of the ephemeral installation.

In 1976, before taking up a Postgraduate at the Royal College of Art, Shemilt made the video performance Art into Protest. This video was shot at the Winchester School of Art. It was also destroyed in 1984 but a sequence of photographs and a series of lithographs and etchings document the artwork. The piece opened with a brick wall with a body form made of chalk with crosses on the hands and head (like targets), and then Shemilt appears naked and fills that silhouette. As the video proceeded, her figure was gradually obliterated and in the last part polythene is the only thing that remains.

In early 1976 Shemilt also made a 16 mm film for the upcoming Degree Show at Winchester School of Art. The only copy of the work was lost after it was sent for a screening at the Film Museum in Copenhagen in the ambit of the International Festival of Women Artists in 1980. The film recorded a performance: in the first scene Shemilt was under polythene breathing; in the following sequence she built an installation made of pictures of parts of the body that were hanged at wires and soft sculptures with pieces of bodies printed on.

Expanding on the difference between film and video in her practice, Shemilt explains:

I kept a clear distinction between the two [video and film]. The 16mm film that I made in 1976 was «stand alone» because it was edited and crafted as an art object within it’s own right.

The videos of that period were intended to be seen as a performance within the context of an installation.[15]

Two years after that, in 1978, Shemilt made Constraint, a video performance in which the artist manipulates and deforms her own body and face with polythene and tape, creating a living sculpture. Only photographs document that video artwork.

In 1979, she was selected for inclusion in the Annual Hayward by her friend and fellow artist Helen Chadwick. On this occasion Shemilt made an installation entitled Ancient Death Ritual, beside which slide images in a carousel changed every minute.

2. Doppelgänger and Women Soldiers: Shemilt’s experimentation with video in the early 80s

From 1979 to 1981, Shemilt was in a residency at South Hill Park Art Centre, where, – as she recalls – there were available well-equipped video facilities. In that context after a three years break from video, and thanks to an award from Southern Arts, she elaborated Doppelgänger, one of the two still existing videotapes from her early production. It was finally recovered and digitised by the AHRC funded research project Rewind[16] in 2011.

Doppelgänger[17] is a video performance in which the artist manipulates her body and her image into creating a phantasmal double of herself.

In the opening scene, Shemilt faces the camera and, dressed very simply, proceeds to take a sit in front of a mirror. In front of her reflected image, she starts to put some foundation on her face with very sharp and almost rough movements. The voice in the background evokes the topic of the double personality through some medical notes on schizophrenia.

As Shemilt continues in the application of the product, her face becomes more and more similar to a theatrical mask. Suddenly she drops the foundation, takes a black drawing pen and starts sketching a self-portrait on the mirror. The artist’s doppelgänger is so created and seems to constitute a part or an extension of herself: she continues to modify its image, mimicking with her face the gestures of applying lipstick. She continues to move in front of the mirror as she checks the result on herself.

Twice during her performance the sequence is interrupted by multi-layered images of the face of the artist, of her naked body or parts of it, to create a sense of multiple personalities and a window to her inner self in contrast with her public image.

The sequence closes with the mirror and the doppelgänger: the presence of the artist has been finally replaced.

The double and the mirror were seminal features in early video artworks.[18] This common element can probably be partly explained with the instant feedback that video provided. The artist could ‘reflect’ him or herself in the mirror of the video monitor while videotaping and could re-watch the recorded piece immediately after it was videotaped. Instant feedback created an instant double of the artist, influencing his or her behaviour[19] and empowered him or her with a sense of control of the medium as he or she could check constantly for example the framing. The possibility of re-recording on the same tape gave also the possibility of creating phantasmatic ‘doubles’ in the video. The metaphor of the mirror was widely employed by art historians and critics. In Italy art historian Renato Barilli defined video recording as a «clear and trustworthy mirror of the action» in his seminal essay Video recording a Bologna (1970).[20] ‘Video as a mirror’ was one of the three ways of the artistic use of video for Wulf Herzogenrath (1977).[21]

In her seminal essay Video: The Aesthetics of Narcissism from 1976, Rosalind Krauss points out that «unlike the visual arts, video is capable of recording and transmitting at the same time – producing instant feedback. The body [the human body] is therefore, as it were, centered between two machines that are the opening and closing of a parenthesis. The first of these is the camera; the second is the monitor, which re-projects the performer’s image with the immediacy of a mirror».[22] Starting from the analysis of Vito Acconci’ Centers, Krauss identifies three elements (monitor, camera, artist’s body) that create a narcissist loop. She even questions if video in general can be considered as narcissist (even if towards the end of the essay she takes a step back on this suggesting three categories of video art that contradict this thesis). For her psychoanalytical interpretation, Krauss refers to both Freud’s theory of narcissism (the change of the object-libido into the ego-libido) and Lacan’s stages’ theory.

Krauss’ seminal interpretation has been challenged and debated in the following decades.

Michael Rush challenged this interpretation suggesting very interestingly that Acconci in Centers is not pointing to himself but to «”us”, the audience, drawing the viewer into the art process».[23]

Furthermore, in her book Sexy Lies in Videotapes (2003), Anja Osswald has also pointed out how Krauss is missing a fundamental point in her argument: as the video doesn’t relay images in reverse as a reflecting mirror does, the outside viewer, and so the category of the Other, can’t be expunged from the context. So for, video (the ‘electronic mirror’) is «rather the reflection of the self reflection».[24] The artist with an almost documentaristic approach would become nothing more than an ‘empty container’. That would be corroborated by the fact that only a few videos, among those analysed by Osswald, employ the term self-portrait in the title. Although Krauss and Osswald don’t agree on the narcissist connotation of these early video performances employing the artist’s body, they both agree that video plays as a ‘psychological tool’. It is video artist Hermine Freed on the other hand that in 1976 pointed out that artists used their own body because this enhanced a sense of control and to have the possibility to work alone.[25]

In the first instants of Doppelgänger, Shemilt addresses the audience directly facing the camera that closes up on her eyes, initiating a dialogue with them. Then she turns her back to the camera and so the viewer. There is a mute dialogue between the artist and her reflection, a sort of closed loop between herself and her image. The mirror is the medium through which the viewer can experience the artist performing in full.

The audience is no longer part of this ‘conversation’ and stares at the artist at work, evoking the traditional painter’s practice and the common use of mirrors for self-portraits.[26]

Little by little a new element emerge: the drawing, the portrait, the double. And this is addressing the viewer directly with its big eyes. It is the gesture of the artist, the act of drawing, that re-starts the communication with the audience. Video as a time based medium allows the artist to show the genesis of that image, the process of its making and the gesture of the artist as part of it. The continuous mix between the action of the drawing (mirror set) and the images of the artist (her face that sometimes ‘looks’ to audience and her naked body manipulated) creates a stratification of layers that open windows in her inner life, in what lies under the image, under the surface.

At the end of the video, the doppelgänger is finally facing the audience with its phantasmatic presence: it has replaced the artist in this dialogue. So what we perceive as the viewer is the artist that uses the video and the mirror[27] as a tool for introspection. Video is not a mere instrument of recording this psychological research but of communicating this introspection to the audience. In this way the artist escapes the risk of narcissism contained in the mirror set and if even partially in the performance to the camera itself.

In this sense, Doppelgänger is not the simple documentation of a performance but a performance made for the VTR. It’s a video art work with its own autonomy, which explores video as a medium and its nature in a very distinguished way: it can be fully ascribed to the genre that Luciano Giaccari in Italy named «videoperformance».[28]

It is also interesting to notice that several early women artists’ video artworks shared similar imagery and common features and themes, sometimes even if the artists did not have a direct contact between each other. This aspect can be especially traced in women artists who were addressing feminist issues, even if not involved in collectives or considering themselves as feminists. Of course this can be also directly linked to the specificities of video as recently acquired medium that at the time artists were interested to experiment.

This fil rouge has not yet been fully investigated at a European level and a comparative analysis of works and practice would be, in my opinion, highly beneficial.

In Video: The Aesthetics of Narcissism, Krauss described only American videos that include double images and mirrors, but similar examples can be found in Europe as well.[29] These include: Oiccheps (1976) and Il tempo consuma (1978-79) by Michele Sambin, Trialogue (1977) by David Critchley, Senza titolo (Mirror) by Goran Trbuljak, Video As No Video by Luigi Viola (1978) and many others. In Italy for example, Renato Barilli describes an early piece by Michelangelo Pistoletto, entitled Riflessioni, produced for the seminal exhibition Gennaio 70 (1970). This artwork, as all the videos from the same exhibition, was lost but from Barilli’s description we can learn it included the use of a mirror and doubles.[30]

Several women artists engaging feminist themes also used mirrors and doubles in a very distinguished way to specifically engage issues of self-representation and body image. Several strategies employed by women artists to include their own body in their videos but avoiding the objectification of it by the male gaze,[31] have been pointed out by theorists and scholars. These for example include dismantled body parts, extreme close-ups, distancing the body in the background[32] or the image of the artist on a monitor.[33]

In her videos, Shemilt employs several approaches to remediate female body image and the use of doubles is one of these. Shemilt started including ‘doubles’ of her body, in form of puppets and casts, in her videos in 1974-75. Before that the artist, who trained as a sculptor, was already using these props in installations. From her point of view, video provided a feasible opportunity of including both these doubles (puppets, body casts) and herself in the artwork. In Shemilt’s videos, puppets are dehumanised representations of the artists’ body that can be manipulated in the performance to camera (in iamdead for example).

Casts are an indexical trace of the artist body that substitute the artist (as for example in Conflict). In Doppelgänger the drawing of the double plays a similar role as a substitute of the artist and her reflection. In Doppelgänger Shemilt’s naked body is also remediated in several ways: it becomes a screen of projections, which create multiple layers, is presented as dismantled in parts or as X-rays.

Examining European women’s video artworks from late 70s and early 80s, the use of the mirror can be found in Tamara Krikorian’s Vanitas (1977), in which the artist is shown near a mirror which reflects a still life on a table and TV monitor in which some TV broadcast is interrupted many times by images of Krikorian – near a mirror which reflects once again the artist and the still life – who narrates her research about the vanitas and the artist’s portrait in art history, inspired by the painting An Allegory of Justice and Vanity by Nicolas Tournier (Oxford, Ashmolean Museum). Quoting the artist, this video is a «self-portrait of the artist and at the same time an allegory of the ephemeral nature of television».[34]

A significant use of the mirror by a feminist artist can be found also in Gina Pane’s video Psyche (1974): at the beginning of the video Pane is reflecting herself in a mirror and draws an image of her face on it, and then cuts her skin, under her eyebrow with a razor. Later the performance continues with the artist cutting herself, licking her breast and playing tennis. In this case as well, the mirror is employed as a tool for introspection (the soul, the psyche).

Another interesting use of mirror is to be found in Etre blonde c’est la perfection (1980) by Hungarian-Swiss video artist Klara Kuchta. In the video, Kuchta seats in front a mirror and combs her hair while a female voice repeats how happiness is linked to being blond. Hair is a recurring motive of Kuchta’s work since 1975. The narcissist relationship between the artist and the mirror is not ceased even when she breaks the mirror into pieces. The voice becomes little by little distorted and finally repeats «La beauté des cheveux c’est sa blondeur, être blonde c’est la perfection».[35] With the friction between the image and the voice the artist addresses the stereotypes linked to women’s beauty.

Dismantled body parts are used by Federica Marangoni’s performance The Box of Life (1979, originally shot in 16mm, later transferred to video),[36] where the artist melts these pieces of a wax double of her body with a blowtorch. As in Shemilt’s video artworks, Marangoni’s doubles are manipulated demiurgically by the artist with her own hands.

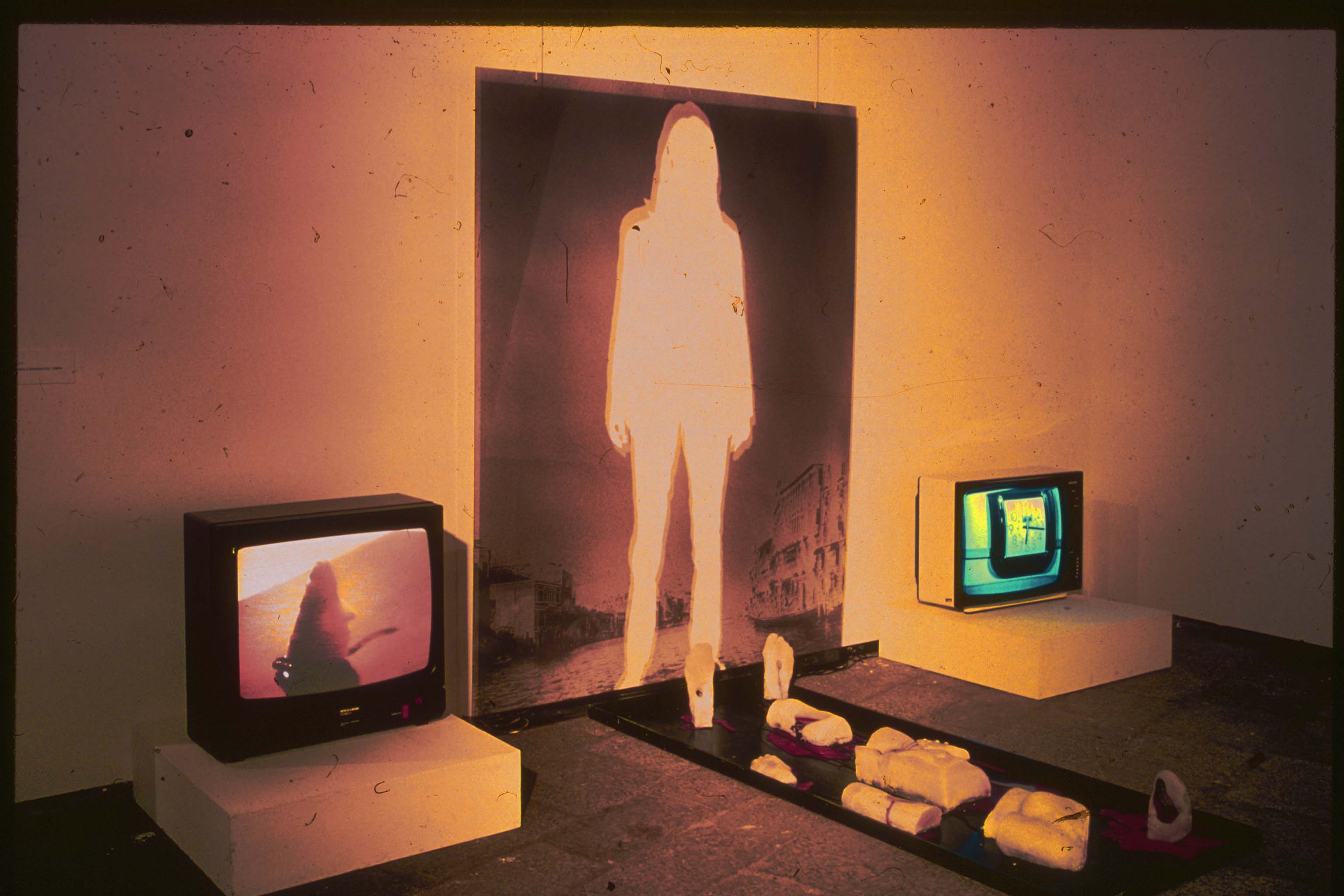

Doubles are recurring theme also in Marangoni’s multimedia installation La vita è tempo e memoria del tempo/Life is Time and Memory of Time (1980),[37] which includes the artist’s silhouette and wax body parts, which once more are melted by an electrically heated table.

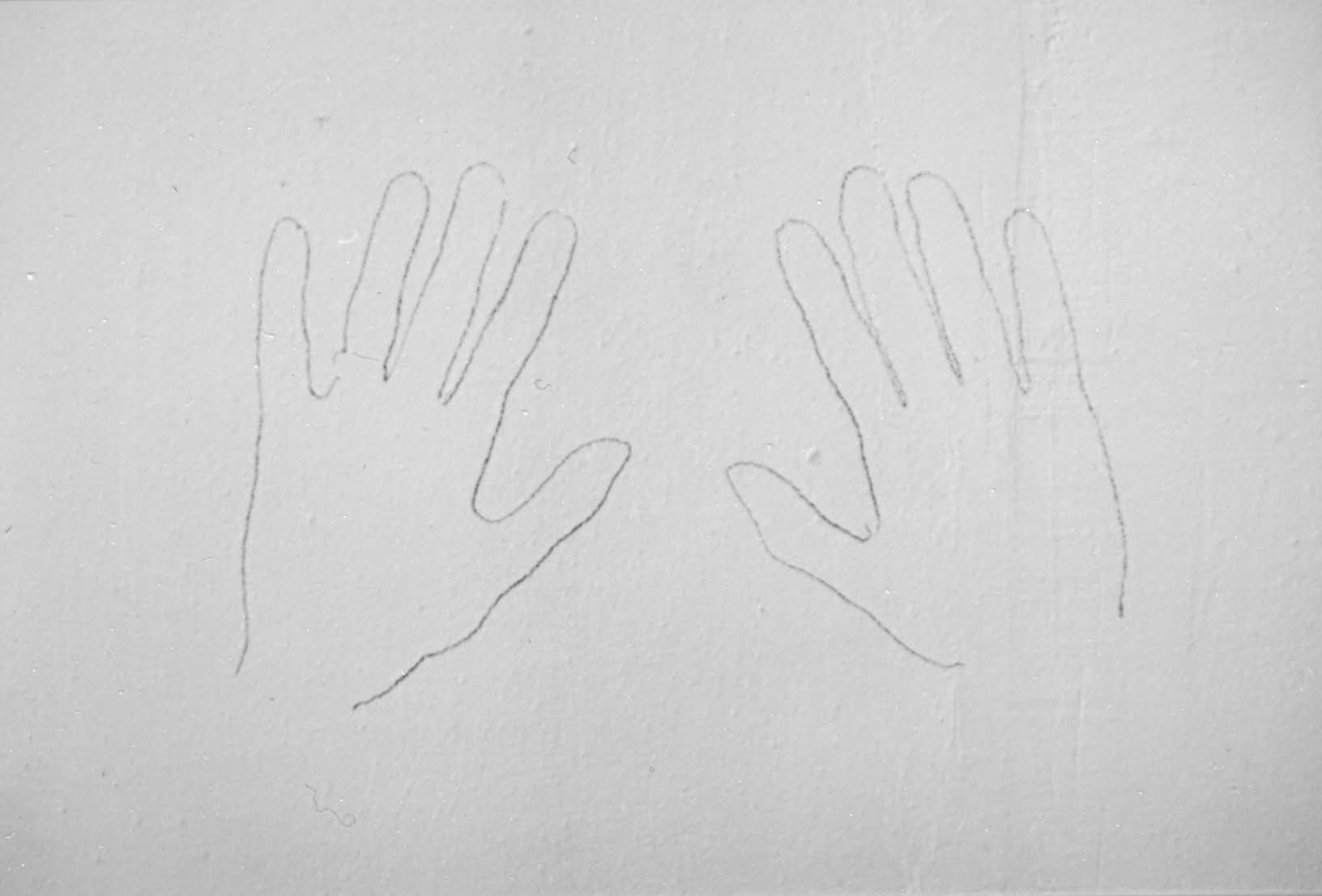

The double through the drawing is also an important feature of Anna Valeria Borsari’s Autoritratto in una stanza, documentario/Self-portrait in a room, documentary (1977).

In the video performance Borsari is confined in a room with a photo and a video camera and explores her inner self and her body in relationship with the confined space. Her voice guides the audience in this personal intimate journey.[38]

Borsari’s performance was held in room at Galleria del Cavallino, «that stayed intact and opened to the public during the entire day».[39]

Last but not least in our analysis of Doppelgänger, one can not forget to mention Sigmund Freud’ s Unheimlich/The Uncanny from 1919, which was originated by a study by Otto Rank entitled Doppelgänger. In his study Freud explains: «These themes [of uncanniness] are all concerned with the idea of a “double” in every shape and degree, with persons, therefore, who are to be considered identical by reason of looking alike».[40] A source of «uncanny» are the «wax work figures»[41] and dismantled body parts,[42] both present in Shemilt and Marangoni’s early videos. Freud links the uncanny feeling of the «double» to the repressed (and then re-emerged) infantile narcissism for which the double can insure immortality. This is interesting as death and the precarious status of the Humankind are motifs shared by both Marangoni and Shemilt’s video pieces, in which both manipulate these doubles creating them or destroying them.

Without pursuing this parallel too far and trying not to give a psychoanalytical interpretation to these early works, anyway Freud’s The Uncanny still provide relevant food for thought and suggestions for these videos’ analysis.

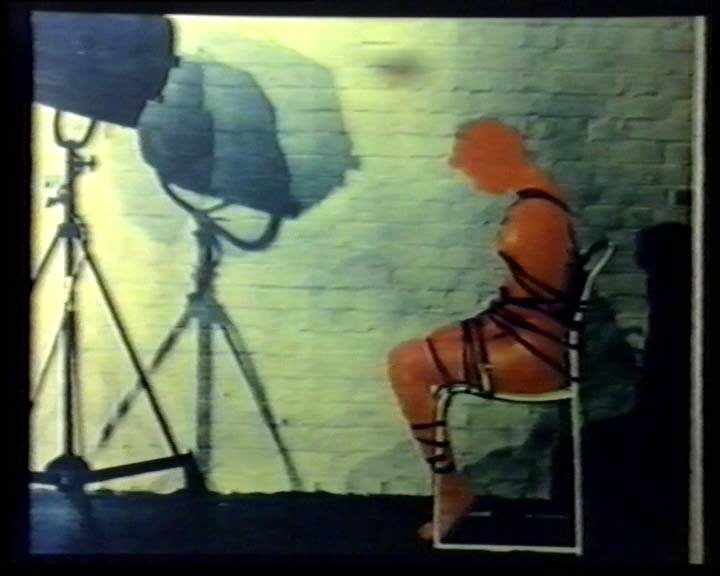

In 1984 Shemilt made Women Soldiers: this video too was recovered by Rewind in 2011. The tape features a series of pictures of women soldiers mixed with photographs of Shemilt’s performances and images from beauty products’ advertisements. In the photographs Shemilt applies a white cream to her face and other she is tied to a chair by strips of film/video tape. The sound is composed of two traces: the first describes rules to apply and work in a military job as a women; the second features advices for women on how to rejuvenate the skin. In the piece so the artist addresses the contrast and contradiction with which the society perceives women’s social role and image.

Make up, for example, is another common feature in women artists’ video and performance which address feminist issues. Beside Shemilt’s Doppelgänger and Women Soldiers, it can be found as for example in Sanja Iveković’s Make up - Make down (1976) and Instructions N.1 (1976-1978).[43] It is also central in Representational Painting (1971) by American feminist video artist Eleonor Antin.

Women Soldiers was the last video made by Shemilt in the Eighties. Later on she dedicated herself mainly to her printmaking practice. But in 1999 in collaboration with Stephen Partridge, Shemilt made Chimera, a four channel video installation that includes several images from her performances and installation Seventies and early Eighties work. Chimera helps to retrace and contextualize Shemilt’s feminist work and her critical use of women’s body. Later, in the 2000s, Shemilt has used video in several occasions, creating autonomous works.

In conclusion, Shemilt’s early video work (and its destruction) constitutes a significant case study on early women artists’ video art, testifying a different use and approach to the medium (compared to the contemporary male video artists and other women artists), a different idea of durée, documentation and future. It shows how video was instrumental to engage feminist themes, and how women artists’ contribution was marginalised or even disappeared in the histories of early video art. Only future research with the support of women artists will open up the possibility of recovering women artists’ experimentation otherwise lost to knowledge.

*This article could have not been possible without the support and help of Elaine Shemilt, Stephen Partridge, Federica Marangoni, Anna Valeria Borsari, Cinzia Cremona, Annalise Jarvis Hansen, Antonella Sbrilli and Adam Lockhart. I would like also to thank Angelica Cardazzo and Archivio Cavallino for the help and support.

1 Shemilt’s works has been represented in several books and exhibition catalogues. These include: J. Stevens, A. Grant, J. Strickland (eds), 150th Anniversary Exhibition of Printmaking from the Royal College of Art Barbican 4 June - 19 July 1987, London, Royal College of Art, 1987; A. Watson, A. Woods (eds), Elaine Shemilt: Behind Appearance, Dundee, Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design, University of Dundee, 1997; L. Allen, P. McGibbon (eds), The Best of Printmaking, Beverly (MA), Rockport Publishers Inc., 1997; 8e Biennale de l’image en mouvement: Centre pour l’Image Contemporaine (1999); R. Box (ed), In-print: evolution in contemporary printmaking: a radical look at the evolution in contemporary printmaking, Kingston upon Hull, Hull Museums & Art Gallery, 2001; A. Weight, Traces of conflict: the Falklands revisited 1982-2002, London, Imperial War Museum, 2002; N. Orengo (ed), II Triennale internazionale d’incisione Gianni Demo; premio Città di Chieri, 2003: Imbiancheria del Vajro, Chieri; Edimburgo 2004/2nd International Triennial of Engraving Gianni Demo; Prize City of Chieri, 2003: Imbiancheria del Vajro, Chieri; Edimburgh 2004, Ferrero (Ivrea), Marianna Editore, 2003; D. Mckenna (ed), Fuoriluogo 15 - Una Regressione Motivata, Campobasso, Edizioni Limiti Inchiusi, 2011; S. Partridge, S. Cubitt (eds), REWIND| British Artists’ Video in the 1970s & 1980s, New Barnet, Herts, John Libbey, 2012; G. Schor (ed), Feministische Avantgarde Kunst der 1970er-Jahre aus der Sammlung Verbund, Wien, Prestel, 2015; L. Leuzzi, S. Partridge (eds), REWIND| Italia Early Video Art in Italy. I primi anni della videoarte in Italia, New Barnet, Herts, John Libbey, expected Autumn 2015.

2 Only few reference sources exist on women artists’ early experimentations with video. Most relevant include: M. Barlow, ‘Feminism 101: The New York Women's Video Festival, 1972-1980’, Camera Obscura, 54, Volume 18, Number 3, 2003, pp. 2-39; C. Elwes, ‘The Pursuit of the Personal in British Video Art’, in J. Knight (ed), Diverse Practices: A Critical Reader on British Video Art, University of Luton Press/Arts Council of England, 1996; C. Elwes, Video Art: A Guided Tour, London, I.B. Tauris, 2005, pp. 37-58; V. Green, ‘Vertical hold: a history of women's video art’, in K. Horsfield, L. Hilderbrand (eds), Feedback: the video data bank catalog of video art and artist interviews, Philadelphia, Temple University Press, 2006, pp. 23-30; C. Meigh-Andrews, A History of Video Art, Oxford & New York, Berg, [2006] 2013. Other sources focus on the parallel topic of the political use of video by women collectives. For this particular aspect see for example: M. Gever, ‘Video Politics: early feminist projects’, AfterImage, II (1/2), 1983, pp. 25-27; S. Jeanjean, ‘Disobedient Video in France in the 70s: Video Production by Women Collectives’, Afterall A Journal of Art, Context, Enquiry, n. 27, Summer 2011, pp. 5-16.

3 ‘EWVA European Women’s Video Art from the 70s and 80s’ started in March 2015. EWVA aims to address this marginalisation and to reassess the contribution of women artists to early video art. The research project is led by Professor Elaine Shemilt. Co-investigator on the project is Professor Stephen Partridge. Archivist on the project is Adam Lockhart. The author of this article is the PDRA on EWVA. EWVA is based at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design, University of Dundee. Materials and interviews are available on www.ewva.ac.uk.

4 C. Elwes, Video Art: A Guided Tour, p. 40.

5 Shemilt, interview by L. Leuzzi, 3 September 2014.

6 G. Romano, E. De Cecco (a cura di), Contemporanee: percorsi, lavori e poetiche delle artiste dagli anni Ottanta a oggi, Milano, Costa & Nolan, 2000, p. 39 (Author’s translation).

7 Shemilt 26 March 2015 interview.

8 Ibidem.

9 L. Lippard, Six years: the dematerialization of the art object from 1966 to 1972, New York, Praeger, 1973.

10 Ibidem.

11 Other significant works in this category would include videos by Helen Chadwick, Rose Finn Kelcey and Alison Winkle. See S. Partridge, ‘Artists’ Television: Interruptions - Interventions’, in S. Partridge, S. Cubitt (eds), REWIND| British Artists’ Video in the 1970s & 1980s, p. 87).

12 Artist’s notes for The Video Show, Serpentine Gallery, London 1975.

13 E. Shemilt, 3 September 2014 interview.

14 Artist’s notes for The Video Show.

15 E. Shemilt, 3 September 2014 interview.

16 Rewind (2004-ongoing) is a AHRC funded research project led by Prof. Stephen Partridge and based at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design, University of Dundee. Archivist on the project is Adam Lockhart. A still from the remastered version of Doppelgänger was published for the first time in S. Partridge, ‘Artists’ Television: Interruptions - Interventions’, p. 88. See also the artist’s page on www.rewind.ac.uk [Accessed 9 July 2015].

17 The video has been discussed in: L. Leuzzi, Notes on Doppelgänger, October 2012, available at http://www.rewind.ac.uk/documents/Elaine%20Shemilt/ES001.pdf [Accessed 8 July 2015]; L. Leuzzi, E. Shemilt, S. Partridge, ‘Body, sign and double: a parallel analysis of Elaine Shemilt’s Doppelgänger, Federica Marangoni’s The Box of Life and Sanja Iveković s Instructions N°1 and Make up - Make down’, in V. Catricalá (ed), Media Art: Towards a new definition of arts, Pistoia, Gli Ori, 2015, pp. 97-103.

18 Ibidem.

19 See T. Sherman, 2005 (ed. 2008) The Nine Lives of Video Art: Technological evolution, the repeated near-death of video art, and the life force of vernacular video… http://www.gama-gateway.eu/uploads/media/Nine_lives_of_video_art.pdf [retrieved Jan 14, 2015].

20 See R. Barilli, ‘Video-recording a Bologna’, Marcatré, 58-59-60, pp. 136-145. The article was later republished in Barilli’s collection of essays Informale, oggetto, comportamento, and recently translated into English in: L. Leuzzi, S. Partridge (ed.), REWINDItalia Early Video Art in Italy/I primi anni della videoarte in Italia, New Barnet, John Libbey Publishing 2015, pp. 21-34, for the quote p. 24

21 H. Westgeest, Video Art Theory. A Comparative Approach, John Wiley & Sons, 2015, p. 22.

22 R. Krauss, ‘Video: The Aesthetics of Narcissism’, October, vol. 1, Spring 1976, p. 52. The article was ripublished in a revised version in Gregory Battcock’s New Artists’ Video in 1978 (pp. 43-64). The essay was translated and published in Italy as: R. Krauss, ‘Il video, l’estetica del narcisismo’ in V. Valentini (a cura di), Allo specchio, Rome, Lithos, 1998 pp. 50-58.

23 M. Rush, Video Art, London, Thames and Hudson, p. 11 quoted in Westgeest, Video Art Theory. A Comparative Approach, p. 54.

24 See A. Osswald, Sexy Lies in Videotapes: Praktiken künstlerischer Selbstinszenierung im Video um 1970, Berlin, Gebr. Mann Verlag, 2003 quoted in Westgeest, Video Art Theory. A Comparative Approach, p. 55.

25 I. Schneider, B. Korot (eds.), Video Art: an Anthology, New York, Harcourt, Brace and Jovanovitch, 1976, p. 212 in Westgeest, Video Art Theory. A Comparative Approach, p. 56.

26 On this specific feature see a brief surveys in M. Bussagli, ‘Lo specchio strumento dell’artista’ and V. Rivosecchi, ‘Lo specchio sul cavalletto’, in Lo specchio e il doppio: dallo stagno di Narciso allo schermo televisivo, Torino, Città di Torino. Assessorato per la cultura, 1988, pp. 193-199 and pp. 204-219.

27 Much has been written both on the use of the mirror in the artist’s practice and on the symbolic role of the mirror in art history. Starting from the XV-XV century to today the mirror in the history of art has deeply changed its meaning. From initial symbol of luxury and pride during the Renaissance, in the early XIX and XX centuries the mirror come to play a more complex and wider range of meaning including introspection. For a survey on the use of mirror in contemporary art see: E.C. Simeone, Lo specchio e il doppio tra pittura e fotografia, Rome, Aracne, 2008.

28 For a definition of videoperformance from Giaccari’s classification (1972) see R. Berger, J. De Sanna (ed.), Impact art video art 74: 8 jours video au Musée des arts decoratifs, Lausanne, Groupe Impact, 1974, pages without number; L. Giaccari, ‘La videoteca – la classificazione – la mostra’, in M. Meneguzzo (a cura di), Memoria del video 1. La distanza della storia: vent’anni di eventi video in Italia raccolti da Luciano Giaccari, Milan, Padiglione d’Arte Contemporanea, 1987, pp. 48-56 (in particular pp. 52-53).

29 See also: V. Valentini (a cura di), Allo specchio, Rome, Lithos, 1998; S. Lischi, ‘Dallo specchio al discorso. Video e autobiografia’, Bianco e Nero, nn. 1/2, 2001 pp. 73-85; M. Senaldi, Doppio sguardo. Cinema e arte contemporanea, Milan, Studi Bompiani, 2008.

30 See R. Barilli, ‘Video-recording a Bologna’, pp. 139-140 (p. 145).

31 Feminist theorists and artists in Europe and in USA in the Eighties pointed out the risk of objectification that comes with including women’s body in artworks. Griselda Pollock and Rozsika Parker wrote that such images «are easily retrieved and co-opted by male-culture because they do not rupture radically meanings and connotations in woman in art as body, as sexual, as nature, as object of male possession». This point of view brought artists and critics such as Mary Kelly, American artist at the time living in UK, to refuse all practices, which not pursue Brechtian distanciation, such as Body Art. For the quote see G. Pollock, R. Parker, Old Mistresses: Women, Art and Ideology, London, Pandora, 1981, ed. London, IB Tauris, p. 130 quoted in C. Elwes, Video. A Guided Tour, o. 48. On this debate see also A. Jones, Body Art. Performing the subject, Minneapolis-London, University of Minnesota Press, pp. 22-29.

32 Feminist video artist and theorist Catherine Elwes wrote: «women on this side of the Atlantic looked for ways of problematizing the appearance of the female body whilst negotiating new forms of visibility». Elwes described several works by women artists in Europe that employ dismantled body parts (including Tamara Krikorian’s Unassembled Information from 1977), extreme close-ups (like Nan Hoover’s Landscape from 1983, Elwes’ There is a Myth from 1984) and distance (as Louise Farshaw’s Hammer and Knife, 1987) in the chapter on Feminism in in her book Video Art. A Guided Tour. See C. Elwes, Video. A Guided Tour, pp. 37-58 (in particular p. 48 for the quote).

33 I would like to thank Dr. Cinzia Cremona for bringing this to my attention. Cremona in her PhD thesis argue German video artist Ulrike Rosenbach’s use of a double image within a monitor as a «tool of separation and distanciation» in Isolation is Transparent, which was presented in the fundamental exhibition Videoperformance curated by Liza Bear and Willoughby Sharp. See C. Cremona, Intimations: Videoperformance and Relationality, PhD Thesis, University of Westminster, pp. 68-69 (http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/15173/).

34 Text by the artist from 1978. See http://www.rewind.ac.uk/documents/Tamara%20Krikorian/TKR053.pdf .

35 See S. Schubiger, ‘Etre blonde c’est la perfection’, in I. Schubiger (ed.), Reconstructing Swiss Video Art from the 1970s and 1980s, AktiveArchive/Museum of Art Lucerne, Swiss Federal Office of Culture, 2008, p. 49.

36 Marangoni’s The Box of Life is available at https://vimeo.com/8945961. For an overview of Marangoni’s practice see: R. Caldura (a cura di), Una generazione intermedia: percorsi artistici a Venezia negli anni ’70, Venice, Comune di Venezia, 2007, pp. 36-39.

37 A photo of the installation is included in V. Conti (a cura di), Federica Marangoni: i luoghi dell'utopia: iconografia e temi fondamentali nell'opera di Federica Marangoni / the places of utopia: iconography and basic themes in Federica Marangoni's work, Milano, Mazzotta, 2008, p. 50. Other images from the installation available at http://www.rewind.ac.uk/documents/Federica%20Marangoni/ITFA008.pdf [Accessed 9 July 2015].

38 D. Marangon, I videotapes del Cavallino, Venezia, Edizioni del Cavallino, 2004, p. 141

39 A.V. Borsari, Autoritratto in una stanza, documentario, Venice, Edizioni del Cavallino, 1978. See also E. De Cecco, ‘Date le circostanze’, in Autoritratti: iscrizioni del femminile nell'arte italiana contemporanea, Mantova, Corraini, 2013, pp. 157-163.

40 S. Freud, The “Uncanny”, Translated by Alix Strachey, 1919, http://web.mit.edu/allanmc/www/freud1.pdf, pp. 8-9 [Accessed 8 July 2015].

41 S. Freud, The “Uncanny”, p. 5.

42 Ivi, p. 14.

43 See D. Marangon, I videotapes del Cavallino, p. 136.