1. The illustrator who became Museum Director*

Count René d’Harnoncourt (Vienna 1901-Long Island 1968), diplomatic cultural mediator and insightful exhibition curator, is usually studied in his capacity of second Director of Museum of Modern Art in New York, therefore his activity as a book illustrator remains mostly unknown. This paper examines two books he illustrated between 1930 and 1931, in order to analyze and highlight this particular skill he maintained throughout his life. Indeed, even during his busy MoMA years, d’Harnoncourt continued sketching installation devices and views of installation devices for museum shows. Drawing was not a secondary activity, but rather the basis of his conception and practice of visualizing (and understanding) spatial and cultural phenomena.

D’Harnoncourt officially held the position of museum director, from 1949 to 1968, under the Rockfellers patronage. In fact he acted as close collaborator and counselor for the collection of so-called “primitive” art assembled by Nelson Aldrich Rockefeller (1908-1979). This collection represents the foundational core of the Museum of Primitive Art (1954-1974), which was then transferred to a proper wing at the Metropolitan Museum, and finally opened to the public in 1982.

The prolific exchange between the director and the collector has been recently traced thanks to a major show entitled The Nelson A. Rockefeller Vision: In Pursuit of the Best Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas (October 8, 2013-October 5, 2014), which included a section devoted to the exhibition of d’Harnoncourt notebooks. In their structure, divided into Catalog and Desiderata, enriched with sketches, photographs, maps, and bibliography, these documents outline the development of the canon of primitive art in the US, and help to reconstruct the collecting interest in the City during the 1950s.

Under d’Harnoncourt’s directorship, MoMA hosted, as reconstructed within the fundamental book by Mary Anne Staniszewski,[1] exhibitions of some relevant examples of non-Western culture, such as Arts of the South Seas (1946) or Ancients Arts of the Andes (1954). In the first case, d’Harnoncourt experimented with the display, by using a complex system of «open vistas moving from one section to another», aiming to present each object «in an atmosphere closely related to that for which they were created and to recreate the experience of the traveller who, in going from country to country, witnesses the sharp contrasts between, as well as the gradual merging culture» - as claimed in the press release.[2] Thus, the curator asked the Mexican-born artist, Miguel Covarrubias (Mexico City 1904-1957),[3] to realize four coloured reproductions within the catalogue. Covarrubias was a man of many talents. He was a reputable advertising illustrator, but also a stage designer, and caricaturist, working for many important American magazines such as the already mentioned Vogue but also The New Yorker, and Vanity Fair. Covarrubias was a collector too, and an anthropologist, particularly interested in material culture and artistic production of Pre-Columbian Mexico.[4] That is why d’Harnoncourt involved him, with its ability and anthropological attention, in the reproduction of some sculptures included in Arts of the South Seas.

These exhibitory projects represented an attempt to stimulate curiosity and interest towards these cultures, «not to give a complete representative picture» but to «serve as an incentive to further studies», as d’Harnoncourt wrote in the introduction to the catalogue for the show Ancients Art of the Andes.[5] It all went unisonous according to Alfred Barr’s vision of the museum as a living laboratory, in whose experiments the public is invited to participate and to learn from. Several years later the direction undertook by d’Harnoncourt his anthropological openness was pursued, at MoMA, by William Rubin with the extensive project show entitled Primitivism in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern (1984).[6]

2. Mexican years and d’Harnoncourt network

Around 1925, having left his motherland (Austria) and his studies in chemistry upon his family’s financial losses, René d’Harnoncourt moved to Mexico City, where he soon started dealing in antique Mexican objects and furniture. He had the chance to develop an already refine taste and, furthermore, to establish important contacts. He was, in fact, part of the American circle centered on Dwight Morrow, US ambassador to Mexico, and his wife, Elisabeth (1873-1955). D’Harnoncourt was soon asked by ambassador’s wife, Elisabeth, to illustrate her Mexican-inspired children story The Painted Pig, which was first published in 1930. In 1929, a year before that publication, Mexican-based Italian photographer Tina Modotti (Udine 1896-Mexico City 1942) realized a quite ‘cryptic’ – such is the adjective chosen by Jennifer McLerran – portrait of the Count, entitled René d’Harnoncourt Marionette. On the right side of the photographed composition stands d’Harnoncourt, presented as an elegantly dressed giant puppet, located in a miniature space, between a theatre stage and a bourgeois domestic interior. The giant-like puppet, whose height was similar to d’Harnoncourt’s, bows to the public and points to the wall on the left side of the photograph. Two religious paintings hung on the wall: a Crucifixion and a praying Saint. This photograph can be easily interpreted as a presentation moment of artworks to a private collector, for a possible acquisition. From an artist’s perspective, especially one animated by communist beliefs as Modotti was, d’Harnoncourt’s activity as a dealer could be easily perceived as a commodifying enterprise. Nonetheless, they had something in common.

«Modotti and d’Harnoncourt – as McLerran points out – were part of a group of influential and predominantly European-educated literati who formed a vital intellectual and artistic community in Mexico City. They found a distinct attraction in the city’s mix of European and indigenous American cultures. Both had a strong interest in the material expressions of America’s native folk culture».[7]

They contribute in the spread of this taste and fascination in their own fields, outside of the country. Covarrubias and the famous muralist painter Diego Rivera attended to the same circles of Modotti and d’Harnoncourt.

The Count also owned a collection of photographs and postcards, dating from 1900 to 1925, which he collected in Mexico at the time he lived there. This collection (1971-1974) was donated to the Benson Latin American Collection at the Texas University Libraries in Austin by his daughter and only child: Anne Julie d’Harnoncourt (1943-2008). These pictures mainly consist of street scenes, in situ, or studio portraits of native residents, markets, patios, or daily interiors views, reproductions of paintings, or of museum spaces. Undoubtedly, these served as sources of inspiration for his sketches and studies, and they testify his anthropological interest for every aspect of the country and its inhabitants.

The first show d’Harnoncourt was asked to curate – entitled The Loan Exhibition of Mexican Arts (1930) and organized at the Metropolitan Museum, previously shown in Mexico City – was «due to the initiative of Dwight W. Morrow», as reported by the bulletin of the Museum.[8] The name of the ambassador recurs and the occasion allowed d’Harnoncourt to officially distinguish himself as a fine expert in the matter of Mexican culture at large.

The selection was previously shown in Mexico City under the patronage of Mexican Government from June 25 to July 5 1930, in the building of the Ministry of Public Education. The exhibition comprised early and contemporary examples of fine and decorative art, «assembled in an attempt to show the artistic aspects of the origin and development of Mexican civilization from the Conquest to the present».[9] The selection stressed the Mexican resistance toward Spanish art but, at the same time, also the influence of models provided by the Conquistadores, by molding pieces according to national concepts and by leaving out those elements that Mexican artists and craftsmen could not have understood or created. As d’Harnoncourt concludes in his text, «such a power of resistance is proof that Mexican art results from the desire of a race for spontaneous and true self-expression».[10] This ambition to seek genuine forms of expression nourished d’Harnoncourt’s interest toward country’s visual topoi which he tried to pursue in his curatorial activity since then, but also, as we will sense, through the illustrations he realized. That it is why, for example, organizers of the show had decided to exclude Colonial art «which is wholly or in great part derived from Spain, to place the stress upon contemporary work in which a thoroughly national style has been evolved through the fusion of indigenous elements with those of European origin».[11] In his brief introduction, d’Harnoncourt then described the so-called Mexican Renaissance, including well known artists and pointing out that «the paintings in the current exhibition are selected to give a diversified and comprehensive review of the present-day activity of Mexican artists».[12]

Diego Rivera was commissioned, in 1932, a mural for the soon-to-be-completed Rockefeller Center in New York City by John D. Rockefeller Jr. The story concerning this destroyed mural is very well known, thanks also to a recent movie on the life of Frida Kahlo (2002). Looking at the dates, it is impossible not to rely Rockefeller’s attention to Mexican contemporary art with the show curated by d’Harnoncourt and presented in the City only two years before. It is impossible not to recognize the role of d’Harnoncourt as a cultural bridge between the US and Mexico.

Inside the taxonomy of items on view in The Loan Exhibition of Mexican Arts, d’Harnoncourt analyzed a particular type:

«Toys are innumerable and varied type, since toy making is an industry in every Mexican village. The life of every section of the country is depicted and every holiday has its special kind of toys, the most unusual being those for ‘day of the dead’. For this peculiar celebration, skeletons of all sizes are made in materials varying from sugar to metal».

3. The Painted Pig

Toys are at the core of The Painted Pig, a story written by Elisabeth Morrow. It represents also the first illustrated book by d’Harnoncourt and was published by Alfred Abraham Knopf Sr., who funded the homonymous publishing house in New York in 1915. According to Sarah Carr’s obituary, published in 2001 in the New York Times, «she met her future husband, Rene d’Harnoncourt, a young Austrian then living in Mexico, when he came to Chicago on tour with an exhibition of Mexican Arts which he had organized for the American Federation of the Arts. They met in the book store at Marshall Fields, where he was signing copies of children’s books he had illustrated, and it was love at first sight».[13] The children book – the one I will examine below – marked a turning point in d’Harnoncourt’s biography.

The Painted Pig – a disputed Mexican toy – is the silent character of a story which takes place in an unidentified pueblo «between smoking mountains and the cactus with red flowers».[14] The story begins with a meticulous description of its main character:

«He was yellow, with pink roses on his back and a tiny rosebud on his tail. He looked fat, but he was fed nothing at all. In his side was a small slit where you were supposed to put pennies, but his little mistress never had a centavo to drop into the hole; so his saving-bank stomach remained permanently empty».[15]

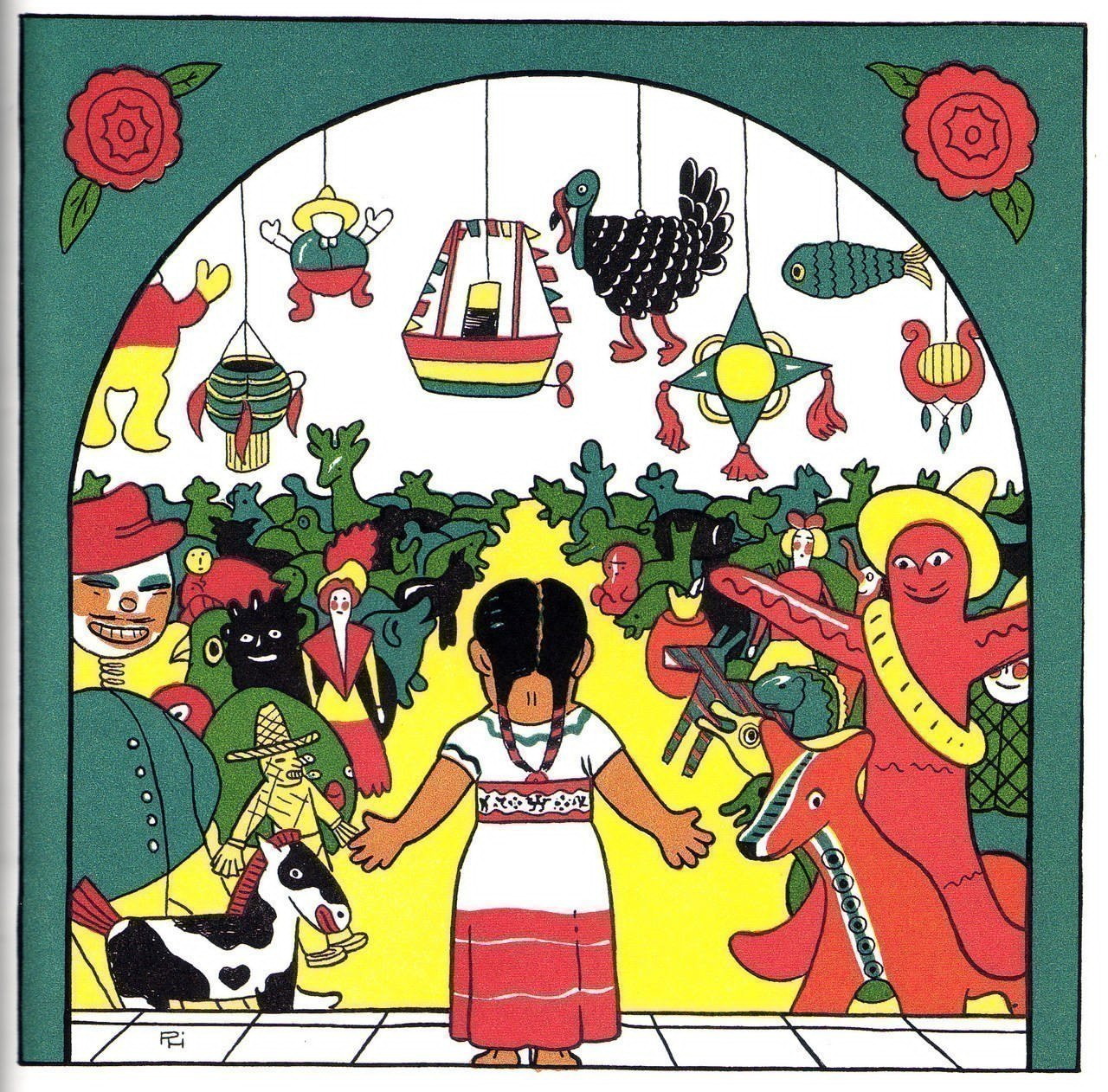

Painted Pig’s mistress is a little Indian girl, called Pita, who «was only ten years old but she wore a long blue scarf and a long skirt like her mother and also big gold ear-rings and a gold necklace».[16] Pita has a younger brother Pedro, who is eight years old. Among brothers and sisters it is common that the youngest likes the oldest one’s playthings better than his. For this reason, Pedro begs Pita to let him play with her painted pig. One day, Pita decides to go with her brother to the market to meet Pancho, the toy-maker, and ask him to make Pedro a pig of his own. But Pancho says: «I’m sure you don’t want a pig; nobody buys pigs any more. What you really want is a donkey. I have a wonderful burro from Puebla with a load of yellow marigolds on his back».[17] With these words starts a parade of toys offered by Pancho to Pedro, which were depicted by d’Harnoncourt: a rabbit, horses, lions, a blue bird, a black turkey, a blue fish with yellow tail, a ship, a clown in stripped trousers.

The rich offer is unable to persuade Pedro who just want a pig like Pita, but possibly yellow. Pancho does not agree to make another pig with the same features so Pedro decides to make his own pig stating that «Pancho needn’t think he is the only one who can do it».[18] But he fails, and his animal ends up looking like an elephant.

The story unexpectedly ends the day in which the children meet Pancho in the market plaza. He is smiling with a savings-bank pig in his hand. «I made him last night » says the toy-maker «he’s a grand pig, fat and strong, and he only costs five centavos».[19] The pig is yellow with blue circles on his back and a large blue dot behind his ear. «It was stupid to make two pigs alike» explains the toy-maker defending his freedom of expression and the need to invent every time, even through poor means, a different and unique toy. Pedro is finally satisfied because «the ears aren’t too big, and the nose isn’t too long, and the legs don’t wobble».[20]

The illustrator, following the development of the story, offers an exhaustive catalogue of the toys mentioned and of the portraits of the characters, as well as of the different sets of the story created by Morrow. Each illustration is contoured by a black line and filled with vivid colors, most notably red and green, the colors of the Mexican national flag, and yellow. Each illustration is framed differently, with geometrical or blooming circular shapes.

4. Mexicana. A book of Pictures

Mexicana is not intended for children, and with its sketches and textual anecdotes offers a «strange mixture of pathos, savagery, sweetness, and cruelty, that Mexico offers to even the most unobservant».[21] In a way it can be interpreted as a counterpart of The Painted Pig, but addressing to adults.

The book presents a selection of little stories, notes, and records of things «seen and heard on marketplaces and along the highways. Unimportant as such small incidents may seem in themselves they are significant as the truest and most spontaneous expression of the people».[22] D’Harnoncourt does not intend to provide a complete picture or to evaluate, classify, or explain Mexico, as was the case of his future MoMA shows of non-Western cultures he had the chance to organize. They simply are, as d’Harnoncourt writes in the introduction, stories isolated from everyday life «that you want to read again and again because you may missed some of the most interesting parts the first time. When you have finished, you will know more about Mexico than if you had read a dozen history books».[23]

Each textual fragment is illustrated with a full-page black and white pencil drawing by d’Harnoncourt, and, after reading the comments and examining the pictures «you will feel that you have actually made a trip to the fascinating country of Mexico».[24] A trip across small villages and city plazas, flourishing nature and architectural features, across inns, churches, fiestas.

D’Harnoncourt was interested in documenting each and every aspect with equal attention in order to highlight every custom or legend that made Mexico different from any other country in the world. While The Painted Pig is a child tale, Mexicana can be seen as a personal and totally free guide to Mexico. Sometimes the interaction between literality and iconicity is amazingly funny, with people dancing and singing and having a happy time, while sometimes Mexicans seem very solemn or sad. An insisted chiaroscuro represents a distinctive aspect of each drawing, stressing once more lyrical moments and attitudes, in contrast with the textual side which often seems to be avulsed of interpretation. D’Harnoncourt included transcriptions of advertisements, for example for artistic photography or theatre performances, whose prices he reports. The author remains loyal to his promise: Mexicana is not intended to judge but to present in a very communicative way. Evidently there is an authorial selection but it is intended to outline common habits and situations, framed and set with notable attention for details. An attention which will also become evident in the displays he will arrange during his MoMA years.

The figure of d’Harnoncourt as a book illustrator, a self-taught ability mixed with first-hand and object-rooted connoisseurship, still needs further investigations in order to highlight a less known but interesting production, crucial in the understanding of his peculiar – we would say even anthropological – attention for artworks and folk objects. In these terms, this production waits to be relied to his photographic collection as well as to his major curatorial activities and to that ‘art of installation’ he was able to show to MoMA audience and to pass to his daughter Anne. Making museum history was in her blood – as had the chance to wrote Dinitia Smith in a 1996 article for the New York Times. In fact, Anne d’Harnoncourt has been director of the Philadelphia Museum of Art from 1982 to 2008 until her sudden death. The journalist, who met Anne d’Harnoncourtin in her home, noted as follows «the house is in many ways narrative of Ms. d’Harnoncourt’s life. There are brightly colored pieces of Mexican folk art from her family’s apartment in New York».[25] Inherited pieces which were assembled by her father, reminding his Mexican stay. Asked about her father influence, she just replied «his enormous love of art and artists. He had a great respect and love for the art of installation».[26] And it is undoubtable that the art of installation exemplified by René d’Harnoncourt derived from an haptic comprehension of the attributes of the artwork itself, no matter of what chronology it belongs to. The display technique is, at the end of the day, a sister of illustration - we could say in more contemporary terms, a 3D composition.

Out of René d’Harnoncourt legacy in the appreciation of Mexican art, even through examples of applied art, more complex connections between New York and Mexico in the Thirties still wait to be focused. This text aims to contribute a step in this direction.

*I would love to express my gratitude to Laura Moure Checchini from Duke University for the comments to the draft of this article. The text is dedicated to the memory of Anne d’Harn.

1 M.A. Staniszewski, The Power of Display. A History of Exhibition Installations at the Museum of Modern Art, Cambridge (Mass.), The MIT Press, 1998, pp. 111-140.

2 Arts of the South Seas, institutional press release p. 2, available at http://www.moma.org/pdfs/docs/press_archives/1131/releases/MOMA_1946-1948_0005_1946-01-29_46129-5.pdf?2010 [accessed 13 february 2014].

3 To contextualize the figure of Mivuel Covarrubias, his network as well as his polymorphic activity see E. Poniatowska, Miguel Covarrubias: vida y mundos, Ediciones Era, Mexico City 2004.

4 M. Covarrubias, Mexico South: the isthmus of Tehuantepec, A.A. Knopf, New York 1954 and Arte indigena de Mexico y Centroamerica, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, 1961.

5 W.C. Bennet (ed. by), Ancient Arts of the Andes (New York, Museum of Modern Art January 25-March 21 1954) New York, The Museum of Modern Art, 1954.

6 W. Rubin (ed. by), Primitivism in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern (New York, Museum of Modern Art September 27, 1984 - January 15, 1985), New York, The Museum of Modern Art, 1984.

7 J. McLerran, A New Deal for Native Art: Indian Art and Federal Policy 1933-1943, The University of Arizona Press, 2009, p. 35.

8 R. d’Harnoncourt, ‘The Loan Exhibition of Mexican Arts’, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Vol. 25, No. 10 (October 1930), pp. 210.

9 Ivi, p. 211 .

10 Ivi, p. 217.

11 Ivi, p. 211.

12 Ivi, p. 217.

13 http://www.nytimes.com/2001/08/29/classified/paid-notice-deaths-d-harnoncourt-sarah-carr.html [accessed 27 february 2014].

14 Ibidem.

15 E. Morrow, The Painted Pig, University of New Mexico 2001 (1930), p. 3.

16 Ibidem.

17 Ivi, p. 14.

18 Ivi p. 22.

19 Ivi, p. 31.

20 Ibidem.

21 A.P. McMahon, ‘Review of Mexicana: A Book of Picture’, Parnassus, Vol. 4, No. 1 (Jan. 1932), p. 33.

22 R. d’Harnoncourt, Mexicana. A book of pictures, New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1931, pages not numbered.

23 Ibidem.

24 Ibidem.

25 http://www.nytimes.com/1996/05/30/garden/at-home-with-anne-d-harnoncourt-a-master-of-the-graceful-sidestep.html [accessed 16 july 2014].

26 Ibidem.