In several respects, two books could not be more different than T.J. Clark’s The Sight of Death (2006) and Svetlana Alpers’s Roof Life (2013).[1] Despite their stylistic and ideological distance, they both resonate with fundamental concerns that are rooted in the experience of every art historian, or at least of those art historians who do not consider the essential – and ultimately inevitable – critical practices of looking at works of art and describing them as neutral, unproblematic activities. Although it is on this deep level that the two books spark a worthwhile comparison, a number of more superficial similarities should not be overlooked. Both books were published by Yale University Press, as clearly reflected in their careful graphic set up, which especially in the case of Clark is strikingly balanced and thought through.[2] Both Clark and Alpers are renowned art historians, who spent most of their academic careers at Berkeley and whose work has been acclaimed, but also heavily criticised. While being credited with fundamental critical acquisitions, their books have often been divisive in terms of their reception.[3] If it is probably simplistic to locate their work in the area of the so-called ‘New Art History’, it is reasonable to see them as constantly committed to innovating their discipline and pointing out the flaws and limits of traditional approaches.

A less radical intellectual freedom would have probably prevented them from indulging in the worst sin for most rigorous academics: writing about themselves and their subjective experience. Both books are non-fictional works in which the narrator-viewer points explicitly to the flesh-and-blood person – and celebrated academic figure – whose name appears on the cover, with an identification that is assumed at all times. I will argue that it is precisely this indulgence, no matter how disturbing or controversial, that enables The Sight of Death and Roof Life to get to the heart of the master problem of art history – translating things seen into words – in illuminating ways. Especially in the case of Clark, the identification of the book’s intended audience is indeed problematic, as the readers he actually aims to address are not the members of the cultivated minority that is likely to look for or come across a book on Poussin.[4] Despite this undeniable contradiction, it would be unfair to label The Sight of Death as elitist without admitting that very few scholarly books could influence and provoke their readers (for the good or for the bad) as powerfully as this one.

Clark’s and Alpers’s readers, even the most irritated ones, will be compelled to look at works of art with new eyes – and perhaps decide to allow themselves the time to look for the sake of looking, without prejudices and second ends. This outcome would be enough to make these books worthwhile, even if everything else were wrong or useless in them – which is not the case, as long as we do not ask them to become what they definitely do not want to be, scholarly writing in the traditional sense. Consistently, I have tried to respond to both authors’ extreme awareness as writers – that is, to their definite stylistic choices and sharp sense of writing as a way of thinking – by focusing on their use of structure, returning motifs and illustrations, rather than simply on their arguments.[5]

The verbal description of works of art sits at the core of both books, whose polysemous titles however suggest two very different approaches to the problem. The Sight of Death fundamentally encapsulates an interpretation of Poussin’s Landscape with a Man Killed by a Snake (1648; National Gallery, London), which Clark developed through several months spent looking at the painting (while it was on loan at the Getty Museum, Los Angeles) and taking notes about it on an almost daily basis – a process showcased in the subtitle (An Experiment in Art Writing) and recorded in the diary entries that constitute the book itself («A record of looking taking place and changing through time»).[6]

Conversely, Roof Life is concerned with no specific work of art, but rather with a whole life spent looking at art and describing it. In order to reflect on what makes the act of looking worthwhile, Alpers’s gaze rests on things as disparate as shadows on a wall, photographs, drawings, menus, fruit and vegetables displayed on market stands.

1. This is not art history

Both Clark and Alpers advocate the importance of «looking», which, they claim, paradoxically needs to be defended and reaffirmed in an age that thinks of itself – and is regularly thought of – as visual.

[…] spending time looking out my window and matching words to what I see makes me feel an odd-man-out in a world in which people don’t stop to look. […] The challenge to looking is the visual age itself. […] Looking is under threat. For lack of use a medium is being lost.[7]

A broader ‘political’ drive is therefore constantly at work underneath their discussion of methodological issues as well as, in the case of Alpers, in the reflection on private matters. In Roof Life the author’s self-awareness as an art historian is everywhere clear and open, even though she expresses no explicit concern for the fate of art history as a discipline and highlights how this book should be separated from her other works («This is not art history and it is not criticism, nor is it some sort of mixture of the two»).[8] Alpers’s experience as a scholar per se remains in the background, with the exception of a number of pages in the final section of the book and a few crucial self-reflexive passages. For example, in the third section of the final chapter (‘Self seen’), when she recalls the frustrating «vexations» of sitting for a portrait which was never accomplished, her experience as an art historian resurfaces to mark a distinction between the artist and the critic and, indirectly, to state her own identity as a writer – a maker in the verbal medium:

I kept a record of the experiment – a sitter observing the artist observing me. […]

The difference in my record was that I was conscious of being an art historian/critic in the studio and taking notes. I was conscious of being a maker used to working in one medium observing a maker at work in another.[9]

In this respect, Clark’s stance is more complex, as The Sight of Death engages with art history and art criticism as institutionalised scholarly practices while consciously forcing their limits. This attitude is conveyed in the preface and, most evidently, in the subtitle, An Experiment in Art Writing, where the verbal shift from «criticism» (not to mention ‘history’) to «writing» is true to the nature of the book. It is this genuinely liminal status (art history/criticism and not art history/criticism) that made the experiment appear too bold to some readers and not brave enough to others. If the obtrusive presence of the viewer-writer and his absolute centrality in a series of idiosyncratic annotations about paintings is what annoyed more conservative reviewers, more radical readers attacked Clark’s concessions, indeed very limited, to traditional scholarly methods and editorial conventions (references to textual sources, endnotes, and captions accompanying illustrations).[10]

In fact, a certain degree of ambiguity is embedded in Clark’s own reflections on his aims and intentions. This ambiguity is at least twofold, as it concerns both the basic methods of art history and much wider political implications. With regard to method, Clark seems reluctant to discuss at length the limits of verbal description («I want to avoid making a meal of the difficulties […]»),[11] but in fact returns to them over and over again.[12] Similarly, he does not want to waste too many words to explain how The Sight of Death relates to his other works, and yet he takes the time to state how the book sits coherently within his «reactive», committed art history:

My art history has always been reactive. Its enemies have been the various ways in which visual imagining of the world has been robbed of its true humanity […]. In the beginning that meant the argument was with certain modes of formalism, and the main effort in my writing went into making the painting fully part of the world of transactions, interests, disputes, beliefs, “politics”. But who now thinks it is not? The enemy now is […] the parody notion we have come to live with of its belonging to the world, […] its being “fully part” of a certain image regime. […]

Here is why the stress has to fall, it seems to me, on the specificity of picturing, and on that specificity’s being so closely bound up with the mere materiality of a given practice, and on that materiality’s being so often the generator of semantic depth – of true thought, true stilling and shifting of categories. I believe the distance of visual imagery from verbal discourse is the most precious thing about it. It represents one possibility of resistance in a world saturated by slogans, labels […].[13]

Hence, Clark’s engagement with the apparently least political of topics, a close analysis of two paintings by Poussin, should not be considered at odds with his long-established radical-leftist perspective. On the contrary, he claims «the ability of these paintings [his ‘conservative’ Poussins] to speak […] to the image-world we presently inhabit, and whose politics we need such (reactionary) mirrors to see», in an effort to counter the «constant, cursory hauling of visual (and verbal) images before the court of political judgment» promoted by the same Left-wing academy which is likely to attack his book.[14] Just as Clark’s political agenda is inseparable from the texture of his scholarly work, so The Sight of Death as a «small, sealed realm of visualizations dwelt in fiercely for their own sake, on their own terms» reacts to the dismissive treatment of images encouraged by his new «enemies».[15]

In his eyes, description is an imperfect albeit not entirely useless way to engage with the «true thought» expressed visually:

Poussin’s thought about these matters does not take the form of a set of propositions. […] Of course these things are paraphrasable (what else have I been doing for the past hundred pages? […]), but they cannot be paraphrased, or held in the memory, very effectively. That is why they ask to be gone back to.

None of this means that writers on art should spend their time wringing their hands over painting’s ineffability; but they should think about why some visual configurations are harder to put into words than others. And about whether there is an ethical, or even political, point to that elusiveness – whether we’d be better calling it resistance than elusiveness.[16]

While contrasting Poussin’s self-stated «profession of mute things» with the general verbosity of art historians, Clark does not attack descriptive practices specifically.[17] However, it is clear that the hundreds of pages of description that constitute his experiment are haunted by a thorough awareness of the conceptual and practical flaws of description as an interpretive tool. While brilliantly pointing out the fragile and tendentious nature of explanatory or interpretive description, outstanding scholars such as Michael Baxandall and Jaś Elsner have concluded that art history as a discipline could not possibly do without it.[18] For Elsner, essentially all art history is ekphrasis and a certain way of combining ekphrasis and photographic reproductions. From an opposite but equally radical standpoint, James Elkins has reflected on art history’s problematic «relation to the detail» and on the violence implicit in any act of visual analysis.[19] Clark himself is not unaware of the dark underside of meticulous looking, as he shows by acknowledging the tension between «seeing» and «probing into».[20]

In Roof Life, the centrality of describing is attested to by the massive presence of descriptions of all kinds, which constitute a large part of the book: these include Alpers’s own descriptions, descriptions quoted from sources, and comparisons between different descriptions of the same object or place. However, meta-textual references to the practice of art historical ekphrasis – and description tout court – are rarer than in Clark, despite the more obvious connections between Alpers’s oeuvre as a scholar and the theme of ekphrasis.[21] This is probably due, on the one hand, to the greater emphasis she places on «looking» and what makes looking worthwhile; on the other, to the fact that Roof life is in no way ‘a study’ and its connections with the field of art history are looser than the ones still present in Clark’s experiment. The greater freedom Alpers allows herself is reflected in the internal diversity and multiple layers of the book’s structure, which includes five heterogeneous chapters preceded by a ‘Beginning’ and followed by an ‘After words’. Each long chapter is subdivided into an irregular number of sections with individual titles, working mainly as a sequence in chapter 1, while responding to thematic arrangements in the other chapters.

In fact, the first chapter (‘The Year 1905’) is by far the most narrative and the most concerned with chronology. The fascinating reconstruction of the story of Alpers’s Russian grandfather (Wassily Leontieff) matters less as a biographical (and auto-biographical) piece, or as a case of the writer gathering «historical details» as a trained scholar would,[22] than as an introduction to the theme of «roof life». The ‘roof’ attitude is first recognised in the grandfather’s detachment from events: he is described as always having a «distant view», as being always «at a remove»,[23] always behind things or ahead of them, never in tune with his time. Conversely, chapters 2 and 3 abandon chronological concerns and are structured around a series of topics or episodes. In particular, the eponymous chapter (2, ‘Roof Life’) displays a complex internal organisation, essentially spatial and horizontal, largely dominated by description. The dimension of time is still crucial, but its focus here lies mainly outside history,[24] in the cyclic form of sunrises and sunsets, lights and shadows seen through the windows. Consistently, the existential attitude of the grandfather turns into a way of looking at things.

After the dense and conceptually decisive pages that conclude the third chapter (‘Only looking’) – to which I shall return – chapter 4 grants the readers some solace, while testing their patience with random notes taken by the author «stalking food» at markets and stores in different cities over a few decades. At first, it is hard to understand the place of these lengthy records of alimentary findings in the project of the book, especially because the notes are presented in their original and unedited form, albeit accompanied by comments added at the time of writing. However, the chapter becomes less surprising if one goes back to the book that gave Alpers her fame, namely The Art of Describing (1983), in which she focused on the non-narrative quality of Dutch painting, arguing that its human figures, domestic interiors, and still lifes had too often been analysed with «tools first developed to deal with Italian art».[25] Furthermore, the solitary enterprise of cooking is explicitly compared to the isolated condition of writing, and the author’s «distant» take on food resonates with the overarching theme of the book.[26] The final and shortest chapter is devoted to Alpers’ «experience of being photographed, or painted or drawn».[27] In a sense, the gaze finally turns inwards, but through the mediation of external images, extensively described by the writer-sitter – portraits that allow the «self» to be «seen».[28]

By contrast, the experiment of The Sight of Death, its nature of visual performance and writing exercise, formally translates into a repetitive structure, without chapters, based on the simple chronological sequence of diary entries recording each session of looking and taking notes. The randomness of the process is intentionally preserved, despite the partial revision of the notes for publication («The first thing that caught my eye this afternoon… […] a second later, I noticed…»; «This morning almost the first thing I saw…»).[29] Clark himself acknowledges the importance of this ‘informal’ format in his double definition of the book: a «sequence of diary entries» and a «study of two pictures by Poussin»,[30] a diary and a monographic treatment of two paintings turned into one by the unique and obsessive experience of seeing the paintings repeatedly. Especially in the first part of the book, the more traditional questions of art history seem to drop on the page almost malgré Clark’s intentions, prompted by his ‘naïve’ experience of viewing under different conditions of light. For instance, «here is the first ‘scholarly’ question that seems to matter»,[31] he writes as he wonders about the original conditions of viewing of the two paintings. Later on, he makes clear that the answers he might be seeking in the literature on Poussin will respond to questions prompted by his «deliberately ignorant and exclusive looking».[32]

In the final part of the diary, written after the London painting had left the Getty, Clark recalls the months he spent reading about Poussin and looking at other paintings around the world. By his own admission, some of the earlier entries, in particular the ones displaying a higher number of references, were heavily revised by adding later notes to the original materials produced in Los Angeles.[33] In keeping with Clark’s claim that in The Sight of Death he «submitted to pictures», the internal chronology of his rewriting moves from remarks based on pure looking to arguments based on primary sources (Félibien) and critical writings on Poussin (Louis Marin, Erwin Panofsky, Denis Mahon, etc.).[34]

The unusual concentration of scholarly elements in the entry of 8 February deserves a closer analysis in this respect. Partly as a reaction to the puzzling conclusions about Poussin’s handling sketched in the previous entry (7 February), Clark shifts his attention to texts, in which however he finds no decisive clues, ultimately realising that his words feel even farther from the painter’s handling that they did before. Therefore, he goes back to the pictures, this time engaging in a digression about the presence of tiny human figures in Poussin’s oeuvre: having lost his way in the process of pure looking and pure reading, he seems to seek solid ground in one of the most traditional tools of art history, the painter’s Catalogue Raisonné.[35] As a consequence, six paintings by Poussin are reproduced in the following pages,[36] followed by an extended quotation from the inventory of Jean Pointel’s collection, which included no less than twenty-one works by Poussin. The inventory was written with the help of the painter Philippe de Champaigne, to whose concise descriptions Clark interpolates a number of brief informative glosses that make the relevant painting identifiable for his readers. The combination of the two voices on the page, one speaking from the seventeenth century (in French) and one commenting from the present (bracketed, in modern English) conveys a respectful and minimalist attempt at putting paintings into words, in which even the simplest descriptions reveal their complexity through Clark’s comments on specific lexical choices made in the inventory.

Possibly the oddest trace of the book’s placement at the limits of scholarly territory can be found in the index, which, alongside primary and secondary sources and works of arts, lists a number of themes, genres and critical concepts that are much more difficult to pinpoint («structure versus materiality», «momentariness, painting of», «repeated looking», «ethical balance», etc.). Would any reader be able to make use of them before having read the book, and, more importantly, would the use of an index be appropriate for a book that clearly asks to be read in its exact sequence of words and photographic reproductions? Jumping from one diary entry to a much later one (or vice versa) would mean exiting the experiential space Clark sets up for his readers, ultimately disrupting the process in which he asks them to participate by following him in his daily visits to the gallery and looking at Poussin ‘over his shoulder’.

2. Looking

Neither The Sight of Death nor Roof Life are concerned with the act of looking in a generic sense. The point is not understanding how looking works or what it implies but showing why we should be looking more, and more attentively. In both books the artificial and lengthy viewing performances of the authors are meant to work against the average, neutralised habit of looking, yet the objects and rituals of looking are very different in the two cases.

The Sight of Death focuses almost exclusively on two paintings by Poussin, Landscape with a Calm (1650-1651; J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles) and Landscape with a Man Killed by a Snake (1648; National Gallery, London), exhibited in the same room during Clark’s stay at the Getty in 2000.

In fact it was the exceptional chance of seeing together two works normally hanging in two different continents that called on the author’s attention, urging him to visit the gallery again and again, and then turn his private notes into a book. Similarly, the writing of Roof Life was allegedly prompted by an external event, which imposed an unexpected turn upon Alpers’s working schedules: the discovery of the true date and place of birth of her father, and consequently the reconstruction of her grandfather’s life. As shown by the volumes she kept on the shelf near her desk, all the other themes of the book were already in her mind, in a way or another, but it was this accidental circumstance that ultimately gave Roof Life its drive and shape.

The different nature of the two events that inspired writing for Clark and Alpers chimes with the difference in the conditions and objects of their looking. In Roof Life, the main visual standpoint can be identified with the author’s New York loft, which becomes an observatory on what is seen through its windows and displayed within its walls, as well as a sort of time machine connecting different places and circumstances of her life. Therefore, the experience of seeing sits at the very centre of Alpers’s everyday life, in a familiar and private space (relatively stable, even though objects are sometimes moved around) opening onto a non-private one (changing and moving in unpredictable ways). Conversely, Clark is compelled to observe and take notes in a space necessarily shared with others, even though both experiences of looking are essentially solitary.[37] In his account of the visits to the Getty Museum, the private dimension remains almost entirely outside the room where the Poussins are hanging:[38] inside the gallery, a space of public display becomes a secluded space for focused visual meditation. The very few external facts mentioned in the diary are trivial circumstances of academic life, with only two significant exceptions: a brief anecdote relevant to a conversation on «iconoclasm in a revolutionary situation», set in the 1960s during a demonstration outside the National Gallery, which provides the background to Clark’s life-long fascination with Landscape with a Snake,[39] and the quick record of a trip to the Western desert, which does not affect his subsequent perception of the Poussins.[40]

Clark devotes his painstaking exercise in looking to every inch of the two paintings’ surface, scrutinized to the extent of becoming blurry, and momentarily isolated from the composition as a whole. In this sense, his descriptions and the accompanying photographic illustrations implicitly raise all kinds of issues concerning the way high-definition reproductions of works of art are used in scholarly books, exhibition catalogues, and websites. A number of arbitrary decisions, including the (un)reliability of colours and the extreme enlargement or reduction of details, can contribute to misleading impressions, first and foremost with respect to the paintings’ relative dimensions. Even a prolonged looking at the actual works cannot easily eradicate the effect of their scale reproductions from our visual memory, all the more so because in real life we are rarely given the opportunity to examine in the same room any paintings we might need to compare.

In The Sight of Death, this issue is addressed by placing the first reproductions of the two Landscapes on two facing pages (pp. 2-3), without adjusting their relative dimensions to achieve symmetry. This layout allows the reader a small-scale experience of the actual difference in their dimensions, which are respected also in the following, larger, full-page photographs of the paintings, each placed on a separate spread (pp. 6-7 and 10-11). Perfectly aware of «what reproduction will never get right»,[41] Clark undertakes the task of looking closely and repeatedly, with the main emphasis being on the latter term, because some qualities of paintings cannot be retained in memory and therefore need to be seen again and again:

[…] that actual interval and placement are things we know we don’t hold in the mind, clearly and distinctly. […] No reproduction will do the job of putting me back in touch with them: they are matters of actual size, actual highs and lows in relation to a viewing body. So I retrace my steps […].[42]

If only direct looking can actually access these qualities, the best way to convey them in words might be as repetitive as the looking itself:

The analytical mode doesn’t strike me as likely to come up with good answers. The response to this sort of question had better be descriptive, reiterative: here is what we are seeing in this particular case: we are seeing this much […] and maybe the “this much” […] is all the explanation we need. I know that the “this much” could simply be an effect of language. But that is for readers and viewers to decide: we all know the difference between a worked-up response and a worked-out one.[43]

Here Clark walks on shaky ground as he seems to posit description as a tautological process – something he himself criticises elsewhere in the book – and simultaneously to identify description and explanation, ultimately allotting to the reader the responsibility to distinguish thoughtful inference from useless speculation. In this respect, the ‘closeness’ of looking is no less problematic than its reiteration. Some details are singled out one day and seem to disappear on the next, verging on the barely perceptible; some others are visible from up close but not from a normal distance, and so on. What kind of «looking» is this? Could the author be stretching the possibilities of sight to an extreme?

Microscopic descriptions are often accompanied by photographic reproductions of enlarged details, which constitute a double-edged tool in the hands of the reader. On the one hand, illustrations encourage readers to look for themselves, embarking on their own visual experiment through the pages of the book; on the other, the careful placement of pictures in the page layout and the interaction of description and reproduction tends to corroborate the relevant explanation. Significantly, in most cases Clark’s verbal description precedes the reproduction, so that the reader’s looking is influenced and directed by his words. As Elsner has noted, to some extent the use of illustrations in art history is always problematic, as photographs themselves are a form of «visual ekphrasis», no less biased than any verbal ekphrasis.[44] However, The Sight of Death seems to counter this ambiguity by radicalizing it and consciously disclosing it to the reader. In fact, through its pages we are continuously alerted to focus on looking – an effective antidote to passive reception – and at the same time left wondering whether this kind of close looking would ever be possible outside the book, in real life.

At times, the process of seeing itself seems to be mediated by memory («I think I remember the steep angle of the hillside…»),[45] with a movement from seeing to remembering and then to seeing again, as in the case of the tiny figures to the left of Landscape with a Snake, with a permanent uncertainty between sight and memory:

[…] small as they are […] the figures are meant to fixate; and they do, once seen. Even from normal viewing distance, six or more feet away, they register. Equally, they can be repressed. I know I have noticed them before, looking at the picture in London. And now I realize that at least once over the past few days I half-remembered that there was “something there” […]. But the half-memory passed and did not lead to me actually looking: it was only today that I saw them, immediately […].[46]

I for one am convinced that I’m still seeing the bending boy’s body and arms, not remembering them and reading in. The most gripping small figures in Poussin are those placed at this threshold between seeing and remembering.[47]

When recording these fluctuations in his notes, Clark often uses the verb «register» to mean ‘do not escape the eye’. This word evokes the sense of an almost technical monitoring of the level of things appearing and disappearing from view, as well as the idea of an inventory of the visible, to which not all details have access from the average distance at which we conventionally look at paintings. Another revealing word is «legibility»,[48] which occurs with reference to the figures that are clearly or barely visible and implies the inevitable verbal component of our viewing that T. J. Mitchell and others have emphasised.[49] Therefore, while overtly claiming for the right of pictures not to be forced into words, Clark himself cannot avoid linguistic traps just as much as he cannot prevent his own carefully designed book from arbitrariness in the choice of layout and reproductions. In the latter respect, he does not take the radical leap into «writing with images» that Elkins would welcome, namely the inclusion of images without captions and call-outs, but in some sections of the book he does keep these interruptions to the minimum.[50]

If Clark looks up close, undermining sclerotized views essentially by way of enlargement and focus on details, Alpers looks from a distance, so that what counters passive looking is estrangement rather than enlargement: «things seen at a remove» appear «strange and so more clearly seen».[51] Her title reveals the centrality of distance – height more specifically (Roof), be it physical or social – and at the same time the wider, existential scope of the book (Life). As Alpers herself explains, roof life stands for more than one thing at the same time: an object, as it «refers to what one discovers looking out from high windows with distant and therefore distinctive views onto the surroundings»; a state of mind, «the way in which one’s attention is heightened and sharpened by confronting things that are unfamiliar or that are made to appear unfamiliar by circumstances»; finally, a condition of life, «the condition of a life lived in that situation – the finding of and separating into one’s self. A writer’s life perhaps».[52]

The first two references implied in the title are the most relevant to my discussion, as they concern the ‘object’ and ‘subject’ of viewing respectively. However, their connection with the third one holds the book together, because, in Alpers’s own words, «taking a distant view […] is better suited to my experience – of things (often, for me, paintings), of people, and passions, of life itself» – and here one might think of her words about Alois Riegl’s distant, «non-participatory relationship» to phenomena.[53] Moreover, her self-identification as a writer seems inseparable from the entanglement of seeing and writing in her experience:

Did the “shock of sight” I experienced in selling the Rothko and the house play a part in my interest in looking at things on my wall in New York? Or are things more tangled up than that? Did the experience of looking at art in the loft shape my account of seeing the painting and the house?[54]

3. Describing

Despite the unapologetic assumption that «one kind of corrective to dogma is looking itself, pursued long enough»,[55] Clark is constantly aware that the repetition of looking, no matter how attentive, will not free us from the need for words to convey what we see. His experiment in art writing engages precisely with this inevitability, and what can make the struggle for description no less valuable than the effort of looking. Similarly, Alpers campaigns for the liberation of works of art – and indeed of objects more generally – from the slavery of words, but she does so from the very heart of a book almost entirely made up of descriptions:

I do not want to describe everything hanging there [i.e. the artworks on the walls of her loft], but rather to explain the interest there is in looking. […] Many words have been written and spoken about pictures. That is fine. I have done it myself. What is not fine is to think, as some do, that pictures are in need of words. If pictures need anything, it is eyes. I do not have a gallery I take people through. The problem is not matching words to pictures, but rather how to keep the interest of looking alive and well.[56]

The value of describing is acknowledged by Alpers by placing this passage right after a reference to her first important contribution as a scholar (on ekphrasis in Vasari’s Lives) and just before the actual description of the objects hanging on the walls: a strange, digressive description, which is placed in the final section (‘Only looking’, pp. 162-170) of the longest and most crucial chapter, ‘Roof Life’, and could be seen as a sort of epitome of the descriptive exercises that constitute the majority of the book. In fact, in Roof Life the first description is found as early as the second page, where it sets the scene of looking-describing and conveys in a nutshell what will be said about the loft and the views from it in the eponymous chapter. This introductory description is followed by several others: descriptions of buildings, of people – often mediated by paintings and photographs –, of moments of the day and light conditions.[57]

In particular, the slow-paced and detailed description of sunrise in the opening section of chapter 2 could be mistaken for the ekphrasis of a painting («the black canvas of the wall is aglow before they mark it»; «Seen together, real ones of wood and faux of shadow, they [water towers] look to be a forest or perhaps a battalion at rest»),[58] being the work of an art historian who has outstanding descriptive abilities, does not reject metaphors, and identifies herself as «a writer by trade».[59] Alpers’s self-reflexive exploration of the descriptive process comes forth clearly in her repeated attempts at putting into words the aqueduct nonsensically placed on the top of a building she sees from her flat:

This is how it looked at first [descriptions in italics follow] […] I have tried again and again to find words to match the aqueduct. The striking thing is that the words come out almost the same every time. Perhaps it is not the repeated words that is striking (printed here as originally written), but rather the repeated need to look again at what I have described [further two descriptions follow, separated by a blank space and in fact very similar in phrasing].[60]

This fragment, which interpolates earlier unedited descriptions into a new description in progress (a description of a description, as it were), is exemplary of the inventorial and cumulative nature of the book’s writing. The section, which frames ‘roof life’ as a «situation», continues by covering the kind of writings, readings and materials Alpers was working with in her New York «viewing box», including «copies of e-mails sent to friends describing things seen to the east and west» and «prints of photographs».[61] The latter are particularly interesting because of their relation to the experience of both looking and describing. At first their function is identified as that of activating a sort of evidentiary circle going from seeing to writing to seeing again («They were taken to record things seen. Sometimes they are quick shots made to verify notes about what I saw»).[62] However, for the author the experiences of seeing and taking pictures often blur into each other, contradicting the merely documentary function of photographs, which in some cases originate the act of looking itself. For these,

It is hard to tell if the camera served as eyes, or if my eyes were focused by the camera. A bit of both. […] I am conscious that in a few instances the camera did not record what I saw, but became my eye – its possibilities of seeing determining mine. One of those […] is on the back [of this book].[63]

And just here, not surprisingly, comes the key moment of self-reflection in and on the making of the book:

Was it a sense that research into the circumstances of the view might distract me from attending to the experience of looking itself? […] But what about the particular experience of looking out from where I live? An interest for me is to try to match words to what I see. I have, for that reason, cannibalized my notes to feed what follows. But it strikes me that writing this is more like painting a picture. There is no beginning and no end. The task is to fill the surface of pages with looking.[64]

The same verb used for the aqueduct («match») resurfaces to express the attempted connection between seen and said, and will appear again in the key paragraph where mere description is submitted to the primary concern of looking («The problem is not matching words to pictures»). Even if this experience of writing feels «more like painting», the writing itself is consciously based on extensive notes, taken over a long period of time. Faithful to the composite nature of Roof Life as a whole, Alpers renounces chronology in favour of a thematic arrangement, while combining revised materials with notes exhibited (at least allegedly) in their original draft. The self-indulgence one might suspect in this nonchalant dropping of raw materials (particularly in chapter 4) is justified, conceptually, by the value the author attributes to record keeping as a way of preserving something about the original view, a distant and immediate one:

The files had nothing obvious to do with each other except that I was keeping them up. It was Roof Life that made the bits come together. The point of them all, by which I mean the point about record keeping but also about the things recorded, is the immediacy one discovers in taking a distant view – of a house, a work of art, vegetables and the other things in a market, oneself seen as others do. The immediacy of distance sounds right.[65]

What unifies the different sections of Roof Life, apart from its multiple identity as an object of seeing, a state of mind, and a condition of life, is ultimately the author who collects fragments of experiences in the physical space of the loft – the I-figure around whom all things seen and remembered orbit. The choice of discarding chronology is consistent with the absence «of beginning and end», which makes this book different from other kinds of writing Alpers herself tried her hand at earlier in her career. By identifying her task as that of «filling the surface of pages with looking», she downplays the sequential component of words and removes the word ‘description’ or ‘describing’. In so doing, she seems to put on hold the gap between seeing and describing, even though the previous comparison («writing this is more like painting a picture») builds on centuries of ekphrasis.

In the key self-reflexive fragment quoted above, Alpers wonders whether her focus on «the circumstances of the view» might be diverting her writing from «the experience of looking itself». The same problem is addressed more explicitly and extensively by Clark when he apologises for the amount of details about lighting conditions that clog the first diary entries:

Too many of the diary entries […] get into gear with a certain amount of fussing over light conditions, outside atmospherics, and how much or how little of the paintings I could see. I have abbreviated some of this, and realize that even so it will test the reader’s patience. […] But light and darkness have to be part of my story. I need to hold onto the pathos of these paintings’ materiality. The last thing I want to happen in the entries is for an ideal of interpretation to replace the odd, sunken, limited leftovers on the wall. Because paintings’ sensitivity to circumstances, I believe, is the other face of their strong, consoling distance from us – their luminous concreteness. They are not fully ours, not disposable and exhaustible, pre-eminently by the fact of their living (and dying) in the light of day.[66]

In fact, I would argue that in both books the prominent emphasis on looking as a physical experience, fully immersed in changing material circumstances, originates from an attempt to overcome the immateriality and dullness of describing. Far from claiming the neutrality of verbal description – both scholars are simply too sophisticated to endorse it – Clark and Alpers seem to point out the heuristic value of that non-neutrality, infusing description with new life by embedding it in specific viewing conditions, such as, for Clark, the bright or dull natural light falling in from the gallery’s «ceiling louvers», alternating or cooperating with artificial tungsten lighting («Wait for a different light on this»).[67]

In the case of Clark, the attention given to the changes in the physical setting of looking and describing is paired with a sharp awareness of the ceaseless transformations in his own writing. The Sight of Death is a meditation about both looking and writing as performances, as processes that do not happen in a vacuum and are subject to a continuous evolution.[68] In a sense, the book seems to investigate the relationship between looking and describing with respect to duration and linearity, as articulated by Baxandall:

[…] if a picture is simultaneously available in its entirety, looking at a picture is as temporally linear as language. Does or might a description of a picture reproduce the act of looking at a picture?[69]

In particular, the choice of the diary format allows Clark to record and convey effectively the almost daily routine of looking and note-taking, reflecting his deeper concern with the transformations of looking over time, as well as with the constraints imposed upon the experiment by the limited duration of the paintings’ cohabitation at the Getty. Temporary inaccuracies, hesitations and contradictions were not necessarily erased in the process of revising entries for publication, because «looking taking place and changing through time» could be represented only «by chronicling it as it happened».[70]

Hence, it is not rare to find Clark correcting himself within the same diary entry, offering a fragment of writing in the making. A case in point is the entry of 26 January, which includes extensive self-commentary and pragmatically shows how one of the most basic practices of art historical description, namely the subdivision of a painting into a number of zones, is most arbitrary and often does not survive the test of a new seeing. We are still wondering whether Clark just took notes or also made a sketch for memory («I think the picture I drew yesterday of the basic sequence of spaces survives the test»)[71] when, suddenly, his discourse takes on a much stronger interpretive turn, moving to the observation of an area of the painting identified as a sort of ‘painting within the painting’ – an area that is then connected to the outcome of the close observation of another detail. The shift from the basic level of description – which we may naively perceive as neutral – to the highest level of speculative interpretation is so rapid that it is hard to be persuaded, and the perplexity fires back at description itself, pointing at its previously unnoticed arbitrariness. This is one of the points where we might be less inclined to follow in the viewer-writer’s footsteps, partly due to the fact that the elements he singles out in the washhouse in Landscape with a Calm would be very difficult to perceive without his verbal guidance and the help of a strategic full-page illustration isolating the detail (p. 35).

The only sections of The Sight of Death in which the layers of authorial revision could not possibly be tracked coincide with the five poems, penned by Clark himself, which are inserted at different points in the book: Landscape with a Calm (p. 40), Pointel to Posterity (pp. 85-86), On the steps of the National Gallery (about the 1960s episode mentioned at the beginning of the previous entry; pp. 120-121), Landscape with a Man Killed by a Snake (pp. 144-145), and Felibién’s Dream (pp. 148-149). The poems are printed in their definitive form, even though we are advised that they were the result of a longer writing process, as the relevant entry provides the date of the «first viable draft».[72] The author explicitly acknowledges the relief their composition granted him, first of all because reading the Poussin literature «instrumentally», in preparation for the poems, allowed him to lower his expectations about the scholarly writings themselves and made their effect upon his own critical writing «more indirect – less superintended».[73] However, something more crucial seems at stake here. In the space of the poems, the task of describing does not appear to be as central as it is for the prose entries and the duty of keeping to the pictures is reduced to the minimum, so that a greater freedom can be enjoyed, without implying a diversion from the main aim of the experiment («I do think a good poem about Poussin would be the highest form of criticism»).[74]

Clark’s choice of keeping track of errors in writing, dynamically absorbing adjustments into a unitary albeit digressive discourse, is substantially different from Alpers’s insertion of unpolished fragments of writing, presented in their original form and singled out in italics. The latter process is consistent with the idea of writing «as painting», as filling up space by unreconciled juxtaposition, so that the horizontality of collecting and filing is stronger than the sense of time passing and rewriting itself, which, by contrast, is key to The Sight of Death. Therefore, in Roof Life the notes resulting from looking are part of a wider range of relics in different media, and even the most narrative and chronological chapter displays an essentially visual approach to composition:

I have come full circle to the description with which I began of the man who was my Russian grandfather. The account of his life in his times is like a piece of Baltic amber held in the hand. Pieces of things, inclusions as they are called, are preserved within it – inaccessible, but clear to the eye.[75]

As a mise en abyme of the book itself, this powerful simile conveys the process of filling the pages with looking and the tension between looking and describing, between inventory and description, reflecting Alpers’s interest in «finding, assembling, and crafting», which can be detected also in her scholarly writing proper.[76]

Both Clark and Alpers make different voices heard in their books, as if quoted words, and specifically quoted descriptions, could help them approach the objects of their looking or develop their own self-awareness as writers. Predictably, the range of sources and materials is much wider in the cumulative ensemble of Roof Life, which includes fragments from essays, novels, private letters, transcribed conversations, documents, faxes and emails. For instance, Alpers contrasts the verbal account by her great-aunt Liuba («a lament») to that of her grandfather Wassily («an academic dissertation») and invites the reader to go back to the transcription of Liuba’s conversation with her nephew Boris («Read the script again if you wish»), which is presented and «reads like the script of a play by some later-day Chekhov».[77] Significantly, the above-mentioned crucial passage about the meaning of Roof Life comes right after the discussion of a literary text, a strikingly self-reflexive meditation on Joseph Conrad’s Under Western Eyes:

The device of multiple narrators was used again and again by Conrad to sustain detachment. His resistance to the certainties of an omniscient author makes for tales that are a dizzying web of attitudes – boxes within boxes – that challenge comprehension. The metaphor of boxes is not right, however. For it is vision or multiple views rather than enfolded structures that define his sensibility as a writer. […]

Detachment as we have been considering it depends on engagement. It is one of the forms that engagement with experience can take: things seen at a remove, appearing strange and so more clearly seen. It touches the heart of the matter of this book. Though rather than practicing objectivity (Chekhov) or detachment (Conrad), I prefer to speak of taking a distant view.[78]

Through Conrad, Alpers seems to be indirectly referencing her own compositional strategies, based on the combination of multiple layers and perspectives, which enclose facts, people and places in the «Baltic amber» of her accounts and descriptions. Words themselves can become part of this display, being exhibited on the page, as it were, not merely quoted, while their materiality is described by other words, which for instance identify them as handwritten or typed and provide details of their grain and dimensions. For example, in the List of Alien Passengers on the ship that travelled from Genoa to New York in November 1939, «words print out at a miniscule scale», but on «the computer screen […] can be enlarged until every letter looks crafted by hand».[79] Furthermore, the spatial arrangement of words can be reproduced and pointed out, just as an image:

In a tall lean woodcut designed by Monique Prieto, forms in two blues, an orange and white make a pattern behind a string of words from Pepys Diary set vertically like this

With

a thou

sand

hopes

and

fears

“Sand”, here separated from “thousand”, has a diminishing effect on the word that follows.[80]

4. Showing

In his reflections on art history as ekphrasis, Jaś Elsner does not fail to mention the illusory ‘objectivity’ of formalist description:

[…] what we adduce as formal is in fact not the object’s own object-hood and existence as matter but that ekphrastic transformation which has rendered it into a stylistic terminology. How secure can we be that such ekphrastic formalism […] is no more than a carefully crafted verbal translation whose discursive functionings are as far from the actuality of objects as any other interpretative description?[81]

In fact, the single most difficult challenge consciously faced in The Sight of Death is that of dealing with Poussin’s «handling» through the verbal medium, describing in words the concrete way in which the painter placed strokes and colour on the canvas. Early on, Clark wonders how writing is «supposed to respond to» Poussin’s «combination of discretion and showmanship – without overdoing things».[82] However, in the following entry he does not hesitate to jump right into this difficulty:

As regard the local, material appearances of paint, and what those appearances signify, writing on art is almost never convincing. It overwrites or underwrites them; it strains too hard to see the metaphor in a way of doing things, or is too anxious to respect the way’s muteness and matter-of-factness, and declines into a catalogue leavened with hints.[83]

Clark tries to protect his writing from these antithetical sidesteps (over-interpreting and tautological listing) by refraining for once from his usual method in this book – close looking, essentially – and instead working just from memory («recalling the sorts of passage […] that stopped me dead in my tracks the last few days»),[84] so that we can imagine him sitting or standing at a normal distance from the painting, with his notepad in his hands. It is here that the wording comes closer to some of Alpers’s sentences («I’ll do it from memory, from a distance, not moving in close to check»)[85] and to the unpretentious form of an «inventory», which she herself uses.[86] However, gradually ideas take over, as Clark superimposes them on the list and indulges in generalization («Poussin is […] the painter of the unnoticeable», and so on),[87] following a logical pattern similar to the one adopted in the case of the washhouse in Landscape with a Calm. The interpretive rapture dies out as quickly as it had kindled, sealed by a conventional rhetorical move – mentioning the details he could (but will not) describe – and a consciously anticlimactic coda («It seems futile to try to describe them all. […] But I’m tired – and kids with squeaking Nikes are taking over the room…»).[88]

When Clark actually engages with Poussin’s handling, he does so by looking so closely that his own impressions happen to be altered, contradicted or dissolved in the very process of looking. For example, when analysing in detail the zone with the passers-by and the bagpiper in Landscape with a Calm, at first he contrasts the multiple small patches of colour that produce the small human figures to the single green line in which the «trace» becomes «the thing it is [the trace] of»; he then moves on to the blue of the lake, which seems to show the same pictorial treatment of the green line, but on closer inspection reveals itself as fragile, made-up and tentative.[89] In other words, visual analysis suggests that the two logics Clark identifies in Poussin’s material handling of painting are not just present in the same painting, but at times are literally at work within each other, even when one of the two seems to dominate, as in the surface of the lake.

Predictably, the mention of the touches of colour in the water is supported by the photographic reproduction of the relevant detail, on the following page.[90] In this case, enlargement becomes particularly controversial because it shows things it would be almost impossible to see even looking at the painting closely. Right after his descriptive tour de force, Clark imagines his readers «may find a touch of madness […] or maybe pathos» in many of his diary entries,[91] and wonders whether he might be pushing his experiment to an extreme:

I seem almost to be setting myself the task of recapitulating in words every move in Poussin’s process of manufacture […]. I know there is something excessive, and maybe ludicrous, to entering this closely into someone else’s imagined world. But these diary entries are partly meant as an argument in favor of such entry. They are meant as an apology for (a glorification of) painting’s stasis and smallness and meticulousness […].

This is the real pathos in what I am doing, I think: that ultimately these entries are my way of arguing with the regime of the image now dominant; and inevitably, therefore, I shall call on my pictures to do too much work – to stand for an ethics and politics I find I can state only by means of them. But one side of me goes on believing that Poussin will let me.[92]

The harsher adjectives used in this passage («excessive»; «ludicrous») are not far from Elkins’s attack on visual analysis, yet Clark’s admission of his own excess is one with his defence of it, on the basis of a greater good, namely a ‘political’ statement against the current state of looking and imaging. The active involvement of the reader is crucial to the book’s aim, as Clark imagines a viewer most likely to be challenged and puzzled by Poussin’s qualities of «stasis and smallness and meticulousness»,[93] which are at odds with the dominant image regime.

In this respect, the careful placement of illustrations and descriptions in the layout exerts an ambivalent influence, eliciting from the audience a combination of heed and freedom, passive and active participation. On the one hand, reproductions are called to stand for the concrete element the words cannot account for, providing «that bottom line of ‘thereness’ in which the text’s argument can finally be grounded».[94] While «pointing out», deictics, and direct addresses to the reader had been central in ecphrastic writings since antiquity, explanatory description in art history and criticism was deeply affected by the introduction of the reproduced object, implying a shift from informative to «ostensive» discourse, as Baxandall observed.[95] On the other hand, Clark’s invitations to the reader set up the experience of the book without exhausting its potentialities, which lie in the ever-changing interactions of reading and looking.

In particular, The Sight of Death displays a significant number of operative instructions addressed to the reader-viewer, who is encouraged to perform specific visual experiments – with the help of photographic reproductions – in order to verify the arguments proposed on the same page. The most straightforward invitation to the reader concerns the simple act of looking at a certain detail or motif («Look at the drawing of the cornices…»; «Look at what he does with shrouded bodies…»),[96] at times made easier by the photographic enlargement of the relevant detail on the facing page («Look at every stroke… […] Look at the one […] Notice the stone on the foremost shore in Snake»).[97] A more complex visual operation is requested when the reader is asked to hide a given section of the picture in order to perceive the visual ‘weight’ of that section or its colour in the overall composition («If you do the business of blocking out the two of them with a thumb, you see immediately how…»; «Without that yellow (using a thumb to block it out) the picture is soulless»).[98]

Whenever a comparison between two or more paintings is invited, the reader might have to leaf backwards and forwards through the book to create the visual conditions for the actual confrontation. The great majority of photographs reproduce Landscape with a Calm and Landscape with a Snake or details of them, alongside other paintings by Poussin, whereas there are just four illustrations of works by other painters (Valentin de Boulogne, Chardin, Pissarro, Manet), plus a detail of Antonio del Pollaiuolo’s tomb of Sixtus IV, a relief from Selinunte and ancient sarcophagi.[99] The strong unbalance in numbers induces a fundamentally self-enclosed experience, in which readers-viewers are asked to stay with the two Landscapes, to be absorbed by them alone – very much in line with the steady focus suggested by the two epigraphs placed after the preface.[100]

Consistently, the inclusion of the few references to other painters does not depend on their relevance to the argument, as we would expect in more traditional art history; rather, on their ‘accidental’ role in the author’s process of thinking and then writing, which is shared with the readers alongside the looking. For instance, it is difficult to miss the sophisticated pleasure of Clark the writer in using Pollaiuolo’s scorpion by contrast, as a witty way to explain his use of the word «dialectic»,[101] or the way he overplays his unconscious associations to modern paintings at the expense of more traditional comparisons («I realize that unconsciously I have been reading the path’s final orientation by analogy with the one at right in Pissarro’s great Climbing Path at the Hermitage»; «I saw in my mind’s eye a passage I had often looked at in the mid-ground of Manet’s Music in the Tuileries […] Again, the association came completely unbidden»).[102]

Sometimes the apostrophe to the readers has a specific function in the argument, being used to move gradually from description to interpretation, and from the actual use to the self-reflexive evaluation of descriptive words:

Compare the citadel in Calm […] with a light falling on it that spells out its intricate structure rather than its solidity. […] ‘Illumination’ would be exactly the wrong word for Calm’s effects and behaviours of light.[103]

A further level of complexity is reached when memory and imagination are involved, for instance asking the readers to recall something in their mind («Think of […]»; «Think of…»), to match the description with a mental image or to visualise what is not actually present in the painting («Imagine a man as substantial as the one on the move in Snake […] running into the world of Landscape with a Calm. The picture’s whole mode would collapse»).[104] Here the author extends his influence beyond the control of the reader-viewer’s physical sight, stepping into the realm of inner vision and the potentially infinite pictures his writing may find or produce there. Therefore, for his readers, the perceptive energy accumulated by spending so much time in the company of two paintings paradoxically opens up numberless other experiences of interior seeing and active «looking», working against the apathy of the visual age.

5. «Past tense and cerebration»

Instructions addressed to the reader-viewer are much rarer in Roof Life, as there are no photographic reproductions for the text to point to, with two prominent exceptions.[105]

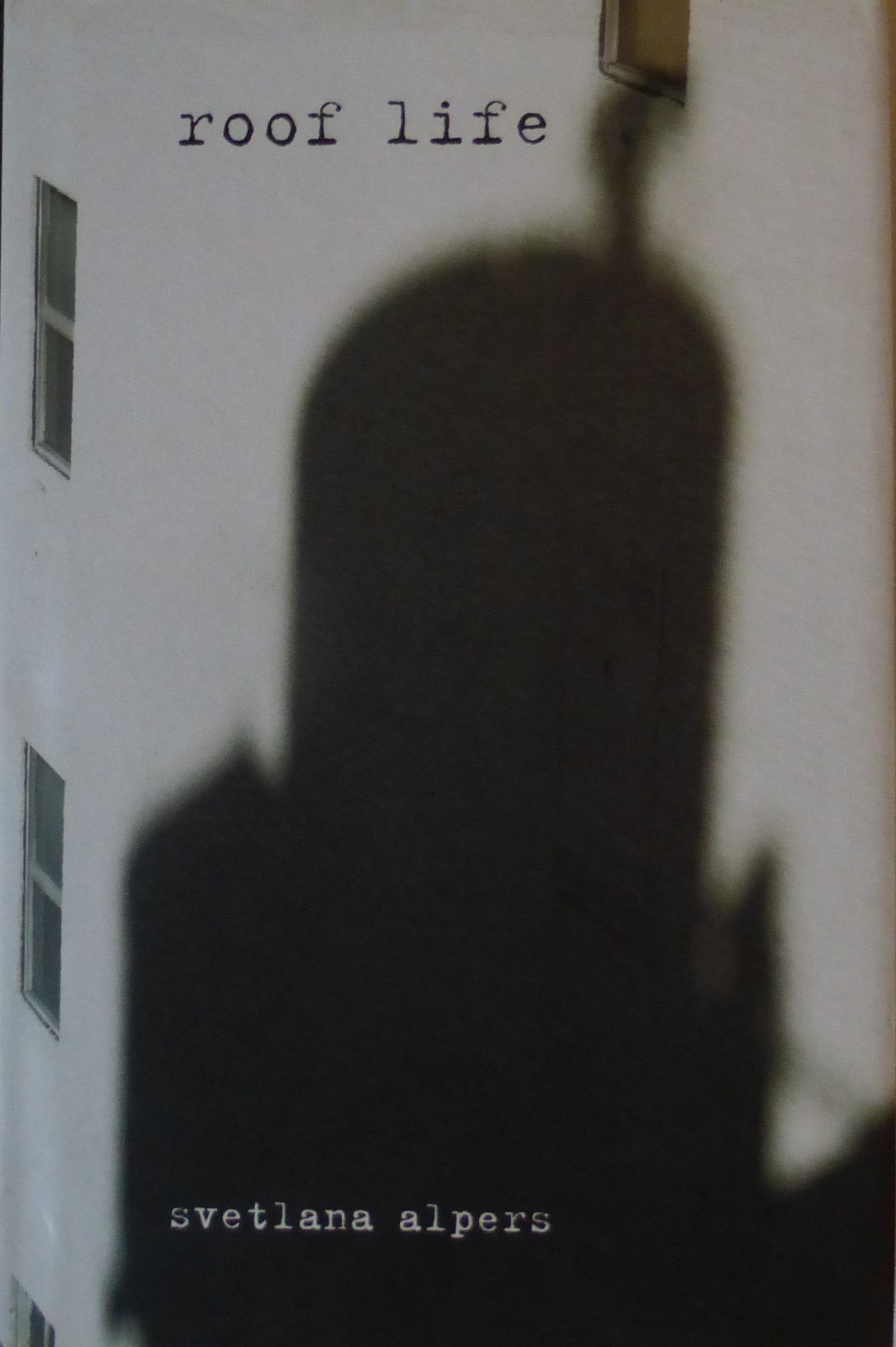

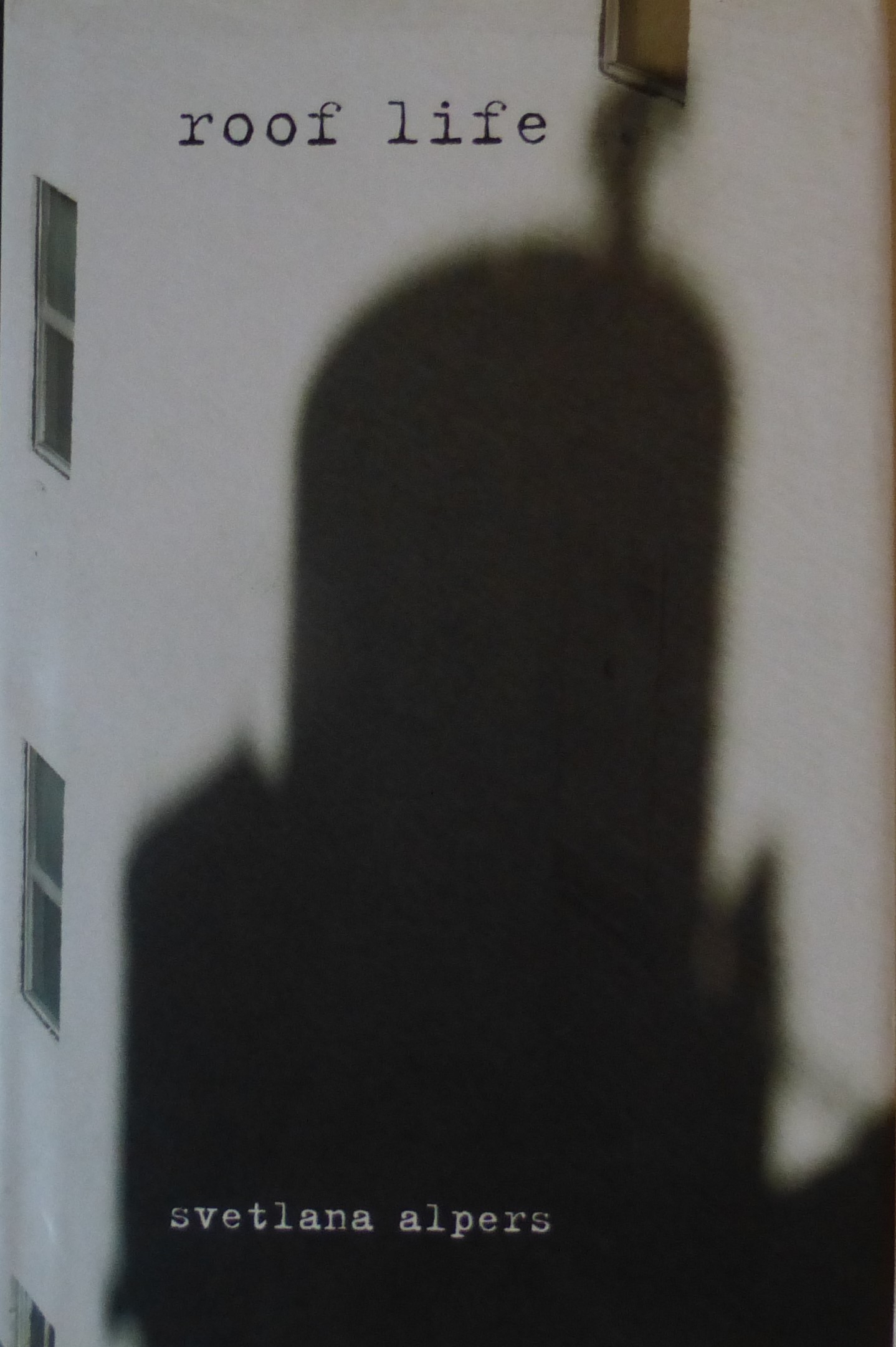

Both the front and the back of the book’s dust jacket display a picture taken by Alpers with her own camera: on the front cover, printed full-page, a water tower being raised and projecting a shadow at the same time, a rare «coincidence» captured from the windows of her loft («Seeing the man building the tower as part of its shadow was like seeing an eclipse. The photograph I made is on the front cover»);[106] on the back cover, enclosed in a slim white frame, the shadow of the author herself projected against her loft’s entrance door. The choice and placement of the two photographs responds to the conceptual range and itinerary of the book, from «roof life» to «self seen», from a look outside to a look ‘inside’, at herself, albeit gathered through an external projection:

What caught my eye was not a shadow, nor even my shadow, but my body as a shadow. That was me, in a different sort of distant view […]. Since then I know that at night, if I turn on the bedside light and walk down the hall, I will appear as a shadow on the front door. […] On one occasion, I took my sturdy Nikon from the back of the filing cabinet and made the photograph that appears on the back of this book.[107]

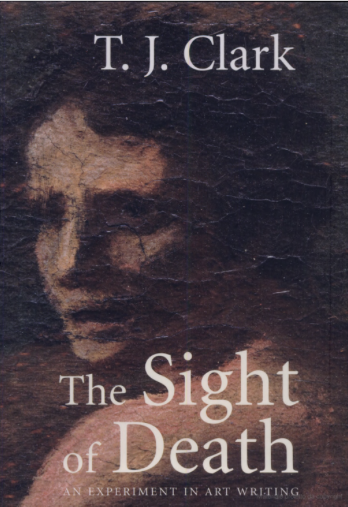

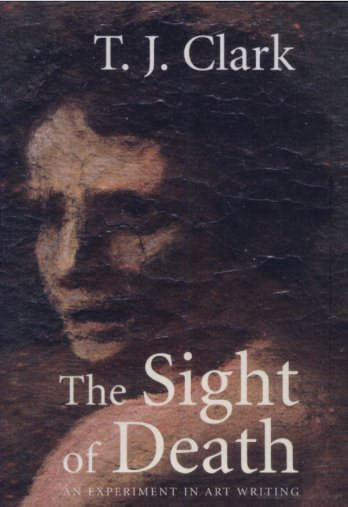

In The Sight of Death, the front cover image shows the powerful close-up of a human face in terror, providing an effective match for the book’s title: a key detail from Poussin’s Landscape with a Snake, enlarged to the point of being almost unrecognisable.

While there is no picture at the back, the outer cover encloses a sort of ‘internal’ cover, composed of two leaves of opaque paper, each showing a detail of the lake and cattle from Landscape with a Calm, inserted respectively after the front cover (detail with the shepherd in blue) and before the back cover (detail with the bagpiper). This visual arrangement brings forth the centrality of Landscape with a Snake in Clark’s overall argumentation, while physically folding the whole experiment in the reflecting waters of the lake, which are the object of his most meticulous analysis and are essential to his interpretation of Landscape with a Calm.

However, before exiting the book proper through its ‘double’ back cover, the last image we are left with is again a detail from the London painting, the washerwoman to whom Clark returns obsessively in his entries, during and after his time at the Getty. In its largest reproduction in the book, which occupies more than half a page, the image of the woman with open and outstretched arms constitutes the conspicuously non-verbal finale of Clark’s performance of sight and writing (made up of looking, describing, and showing). The relevant entry, dated 21 September 2003, neither bears any explicit reference to the detail nor verbally directs the reader to it. The connection between the text and the facing picture is strengthened by its implicitness, so that the political core of the book is finally set free by the juxtaposition:

Affliction and monstrosity, we have to re-learn, are always the true face of utopia – the face it presents as it leaps up out of the immoveable, out of the insufferable everyday.

I think that much of this is articulated […] in Landscape with a Snake. I have held back from saying this until now because I hoped it went without saying. Perhaps I was frightened that putting the ultimate point to the exercise into words would immediately read, for some, as a brutal or desperate allegorization.[108]

After welcoming his readers through an image of horror (on the front cover), Clark bids them farewell with an image of hope and resistance, the open arms of humanity and a potential embrace, whose possibility paradoxically depends on the acknowledgement of the horror itself. The following and final entry, dated 14 November 2003, works as an anti-climax and an epilogue, placed outside the experiment proper, as suggested by its opening words («And so back to reality»).

The effect entrusted to the final reproduction of the washerwoman can be achieved because the relevant detail has been shown and described repeatedly throughout the book, so that by this stage the reader is entirely familiar with it. Similarly, a number of returning motifs mark Clark’s main arguments and obsessions. For instance, after «the base of a pilaster […] which peeps out from underneath the horse’s belly» in Landscape with a Calm is compared to «the stand for a model or a toy»,[109] the image of the stand keeps occurring in the text rather than the pilaster itself, with significant conceptual and interpretive implications. This is an extreme case of dealing with «remarks about pictures», rather than with pictures themselves, in Baxandall’s terms.[110] In fact, Clark’s looking is constantly entangled with his writing:

The kind of looking I have been going in for over the past weeks is special, I recognize: whether I like it or not, it is looking generated out of writing. It is a bit over-eager as a result, a bit gustatory. […] But it seems to me dim-witted to fuss about this, as if words were ever going to constitute a real threat to the paintings they boa-constrict. Paintings are perfectly able to take care of themselves. This is different from the real problem of knowing when an interpretation should stop […].[111]

In the very same sentence in which the author dismisses the fear that paintings might be suffocated by words – ironically hinting at the dramatic advocates of the need to protect images from the tyranny of words – he lets in the image of Poussin’s lethal snake, metaphorically resurfacing in the verb used to describe the assumed threat of words. What may seem just a playful wink in fact reveals a fundamental attitude in Clark’s writing, which is all but neutral, and willingly so. For example, many of his metaphors and similes exceed the visual media. The space in the foreground of Landscape with a Snake «sweeps and flows […] slowly, grandly, like the pull of sound in a nineteenth-century symphony», or the timbre of colour in Landscape with a Calm feels «as if a pianist were just pressing felt onto the strings».[112] If he argues against the use of the adjective «readable» in art criticism, suggesting that «physical and spatial» metaphors should be preferred when talking about pictures,[113] he does not refrain from setting up complex comparisons between the effects of visual features and literary devices:

[…] the “this” goes to full power of Poussin’s thought. The “this” repays looking at repeatedly for the same reasons that a great convergence of metaphor, rhyme, and prosody invites the reader of a sonnet to say it out loud over and over, just to be sure again what it physically, sensuously amounts to.[114]

Clark’s keen attention to tropes is confirmed, indirectly, by his comments on the writing of other scholars, which create a rich texture for his audience to unravel. For example, only by leafing back to the whole reproduction of Landscape with a Snake can the reader-viewer make sense of Mahon’s comparison («the water in Snake, which seems as hard as crystal»), which stands out to Clark as «a trope worthy of Diderot».[115] By highlighting the weight and thickness of descriptive imagery, The Sight of Death suggests that there is a specific and irreducible amount of thought that is made possible by the use of language to describe pictures, just as much as there is a kind of thought that is expressed through a painter’s unique composition and handling.

«Thought», in a different but related sense, features in a poignant sentence from Michael Baxandall’s Patterns of Intention, which Alpers quotes on the page where she explains her interest in ekphrasis and looking:

As M. put it, “Past tense and cerebration. What a description will tend to represent best is thought after seeing a picture”. His emphasis was double: that reports of seeing properly take place in the past, and that words are able to describe not what is seen but thoughts about having seen it. The point is not to celebrate language, but rather to make clear its peculiar status in addressing pictures. The visual interest of pictures, on this account, is something prior to or other than language. Being told that that is an impossibly romantic attitude did not make a difference to us.[116]

Clark would probably agree even on the last, more personal, take on the matter, while being more explicit about his own trust in writing – a trust that both The Sight of Death and Roof Life suggest, and Alpers herself shares, having «spent a lifetime writing».[117] Although descriptions inevitably come after pictures, it is worthwhile not to abandon the struggle to find the right words, trying «harder before admitting defeat».[118] On the one hand, «writers about art» should do their best to keep details undefined when they are;[119] on the other, they should not dismiss the potential of their specific means – including tropes and inconclusive, self-sufficient insights – in generating valuable «thought» about the very same pictures they will never be able to describe.

1 T.J. Clark, The Sight of Death. An Experiment in Art Writing, New Haven and London, Yale University Press, 2006; S. Alpers, Roof Life, New Haven and London, Yale University Press, 2013. The first time I heard someone mention The Sight of Death was at a conference about art history and literature back in 2008. For some reason, that title would not leave me and a few months later T. J. Clark’s book was on my shelf, where it remained for years, unread. The persistent call of the spine was muted by my irrational fear that the book would lose its power if I opened it at the wrong time. It was only after discovering Svetlana Alpers’s Roof Life – a gift from a friend – that I knew it was the right time to read it, and so I did.

2 In thanking their editors, both Alpers and Clark explicitly acknowledge the uncommon format their books required.

3 For an exemplary combination of high praise and poignant criticism directed at Clark see D. F. Jenkins, ‘Farewell to an Idea’, The Cambridge Quarterly, 30.4 (2001), pp. 349-358, which reviews T.J. Clark, Farewell to an Idea. Episodes from a History of Modernism, New Haven and London, Yale University Press, 1999. See also the review by K. Harries, The Art Bulletin, 83.2 (2001), pp. 358-364 and O.K. Werckmeister, ‘A Critique of T. J. Clark’s Farewell to an Idea’, Critical Inquiry, 28 (2002), pp. 855-867. K. Herding, ‘Manet’s Imagery Reconstructed’, October, 37 (1986), pp. 113-124 discussed the harsh reception of Clark’s The Painting of Modern Life: Paris in the Art of Manet and His Followers (1984) among American critics, which in his view depended at least partly on his combination of methods («social criticism and structural analysis […] semiotics […] iconography», p. 123) and his «unconventional diction» (p. 124). On Alpers’s most famous work (S. Alpers, The Art of Describing: Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1983) see L. Marin, ‘In Praise of Appearance’, October, 37 (1986), pp. 98-112 and the more negative review by J. Stumpel, The Burlington Magazine, 126 (1984), pp. 580-581. On the mixture of exceptional descriptions and bold arguments in Alpers’s critical writing see the review of S. Alpers, The Vexations of Art: Velazquez and Others, New Haven and London, Yale University Press, 2005 by M. Westermann, The Burlington Magazine, 148 (2006), pp. 848-850.

4 «The very people Clark needs to confront about […] the image’s supposed hegemony […] those very people are the ones who will not read a book on Poussin» (J. Elkins, What is Interesting Writing in Art History?, chapter 7,

5 On the underestimated problem of «writing as writing» in art history see J. Elkins, Our Beautiful, Dry, and Distant Texts: On Art History as Writing, University Park, Penn State University Press, 1997, and What is Interesting Writing in Art History?

6 T.J. Clark, The Sight of Death, p. 5.

7 S. Alpers, Roof Life, pp. 125-127.

8 Ibidem, p. 1.

9 Ibidem, p. 228.

10 For a very thorough and wide-ranging review of The Sight of Death, see J.A. Van Dyke, ‘Modernist Poussin’, Oxford Art Journal, 31.2 (2005), pp. 285-292, who points out the contradictions in Clark’s experiment («a strong affirmation of the aesthetic, conceived as an emancipatory, resistant, truly human form of cognition, yet all too uninterested in the historical critique of its contradictory conditions of possibility») and identifies it as «a contribution to a Berkeley School of Art History», which would include Alpers herself, especially with reference to S. Alpers and M. Baxandall, Tiepolo and the Pictorial Intelligence (New Haven and London, Yale University Press, 1994). While fully acknowledging the book’s intelligence, James Elkins observed that Clark might have limited the experimental potential of his work because he felt «the residue of disciplinary expectations» (J. Elkins, What is Interesting Writing in Art History?, chapter 7,

11 T.J. Clark, The Sight of Death, p. 36.

12 See, for instance, pp. 93, 118, 125, 132, 161.

13 T.J. Clark, The Sight of Death, pp. 122-123 (emphasis mine).

14 Ibidem, p. viii.

15 Ibidem.

16 Ibidem, p. 184. For the central role of ‘thought in painting’ in Clark’s interpretation of Poussin, see also p. 54 («Any account of Poussin as a painter, even one like mine that wants in the end to talk about the ways his netteté becomes a quality or inflection of thought, not merely the expression of a thought already formed, will always have to return to Félibien’s sense of things») and p. 149 («[…] the attitude to knowledge implied in Poussin’s way of painting […] the balance I have spent most of my time describing»).

17 Ibidem, p. 3.

18 «Every evolved explanation of a picture includes or implies an elaborate description of that picture» (M. Baxandall, Patterns of Intention. On the Historical Explanation of Pictures, New Haven and London, Yale University Press, 1985, p. 1). «Far from being a rigorous pursuit, art history […] is nothing other than ekphrasis, or more precisely an extended argument built on ekphrasis. […] whatever the particular agenda or argument – art history is ultimately grounded in a method founded on and inextricable from the description of objects» (J. Elsner, ‘Art History as Ekphrasis’, Art History, 33 (2010), pp. 10-27; on p. 27, The Sight of Death is mentioned and described as «a spectacular […] and self-conscious example of the extended genre of art-historical description – constructed in the form of a personal diary […]»).

19 «Art history has an open-ended and largely untheorized relation to the detail: it is seldom clear how closely it makes sense to look» J. Elkins, ‘On the Impossibility of Close Reading’

20 T.J. Clark, The Sight of Death, p. 5.

21 Of course here I am referring to S. Alpers, ‘Ekphrasis and Aesthetic Attitudes in Vasari’s Lives’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 23 (1960), pp. 190-215, which Alpers herself mentions in Roof Life, p. 163. On the same page, she writes: «From the start I thought of writing about pictures – using language about visual things – as a strange thing to do. That was part of its appeal. It is different from using language to write about texts».

22 «He [Alpers’s father, in particular in his attitude as an art collector] had an eye, as they say. It was not an art historian’s eye. He took joy in what he saw, loved, and lived with and did not worry about historical details. I am the one who, in taking on objects, sought to secure their identity» (Ibidem, p. 167).

23 Ibidem, pp. 18 and 25.

24 Among the few exceptions to this rule, the most prominent is Alpers’s account of her ‘visual’ experience of 9/11 (Ibidem, pp. 102-105).

25 S. Alpers, The Art of Describing, p. xix. «There seems to be an inverse proportion between attentive description and action: attention to the surface of the world described is achieved at the expense of the representation of narrative action» (Ibidem, p. xxi).

26 See S. Alpers, Roof Life, p. 213 («To stand at counter or stove is a withdrawal comparable to the withdrawal to my desk to write») and p. 211 («There is so much pleasure to food that comes prior to sitting down to eat. That is to take a distant view of it, to return to the theme of this book»).

27 Ibidem, p. 4.

28 «My body drilled into my consciousness through being drawn over time is a self seen» (Ibidem, p. 225).

29 T.J. Clark, The Sight of Death, pp. 15 and 43.

30 Ibidem, p. vii.

31 Ibidem, p. 30.

32 «[…] the deliberately ignorant and exclusive looking I’ve been persisting in ought now to give way to reading and looking more widely. Various questions have cropped up» (Ibidem, p. 149).

33 «I went to see both paintings again occasionally over the next two years, and others connected with them […] and I made my way through the Poussin literature. Some of what I learned there no doubt affected my rewriting of the diary when I turned back to it. Once or twice I specifically added a brief section drawn from later notebooks […]» (Ibidem, pp. 200-201).

34 Ibidem, p. 164; on Félibien, to whom Clark acknowledges an unadorned precision he would presumably wish for himself, p. 54; on Marin, pp. 82-85; on Panofsky, pp. 93-97; on Mahon, pp. 110-114.