In an utilitarian age, of all other times, it is a matter of grave importance that fairy tales should be respected.

Charles Dickens

Pantomime is true human comedy. … With four or five characters it covers the whole range of human experience.

Théophile Gautier

Giambattista Basile’s collection of fairy stories Le piacevoli notti, Charles Perrault’s universally-beloved Histoires ou contes du temps passé, Madame d’Aulnoy’s sophisticated Les contes des fées, and Antoine Galland’s Les Mille et Une Nuits were written primarily with the aim of providing a pleasant entertainment for the Italian and French courts and aristocratic salons. As Madame Leprince De Beaumont published her Magazin des enfants and the Brothers Grimm their Kinder- und Hausmärchen, they hoped that their collections would find a place in English and German household libraries. None of these writers of fairy tales could, however, imagine their future international popularity, and even less that their legacy as ‘classics’ of children’s literature would be kept alive by a Christmas pantomime, the principal theatrical entertainment in England even today.

This highly-admired and quintessentially British form of popular theatre frequently features fairy-tale plots and characters. Given that a great number of pantomime performances, such as Aladdin, Cinderella, Bluebeard, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, The Sleeping Beauty, Puss in Boots, Red Riding Hood, Jack and the Beanstalk, and The Yellow Dwarf are drawn from fairy-tale collections, it appears particularly interesting to investigate the role played by the Christmas pantomime in the transmission of fairy tales, and its impact on English culture.[1] In this essay I therefore intend to draw critical attention to the modalities of transposing fairy tales to the Victorian pantomime. Considering the fairy pantomime’s crossover appeal to audiences of both adults and children, which results from its multivalent construction of transvestite performance, I will explore how fairy pantomimes contributed to the discussion of gender in Victorian England. By addressing these questions, I attempt to shed light on the representation of gender and identity, fantasies of costume and disguise, as well as the development of Western attitudes towards cross-dressing and sexuality.

1. The Rise of Pantomime

Before we can make a case for the pantomime’s engagement with fairy tales, it is necessary to outline the history of its development and the conventions of performance that make this theatrical form unique. Pantomime was introduced into France and then into England by the Italian travelling commedia dell’arte troupes, whose performing style involved a high degree of physical humour and corporeal dexterity. In the English setting, the Harlequinades, that is the pantomimic scenes that featured a pursuit of Harlequin and Columbine by Clown, were performed as the entr’actes between opera pieces.[2] The early pantomimes also included elements of Elizabethan comedies with their customary dumb-shows as interludes between the acts, as well as elements of opera and puppet-shows.[3]

The first play containing the characteristics of a pantomime was staged by John Weaver, a dancing master from Shrewsbury. The term pantomime first appeared on the playbill of Weaver’s «dramatic entertainment», The Loves of Mars and Venus, performed in 1717 with success at Drury Lane, the theatre that was to become the «National Home of English Pantomime».[4] The new and less-experienced company at the Lincoln’s Inn Fields playhouse, headed by the actor-manager and skilled ballet dancer John Rich, matched and surpassed Drury Lane’s pantomimes through the extensive use of French techniques, especially dance.[5] Regularly playing the role of Harlequin from 1717 to 1741, Rich turned this ballet-style form of stage entertainment into an autonomous art form that enthralled audiences of the higher and lower classes alike.

The second-best Harlequin of the century was David Garrick, praised by his contemporaries for his masterfully developed gestural language and pantomimic acting. Though publicly voicing his embarrassment about the popularity of this theatrical form during his management of Drury Lane in the 1750s and 1760s,[6] Garrick contributed to its development by turning the Harlequin character into a speaking part. Thus, as David Mayer reminds us, «pantomime does not mean dramatic action performed by wholly silent actors, although many pantomimes require little speech, and some characters are invariably silent».[7]

Similarly to the early Italian commedia dell’arte scenarios, the scripts of the early English pantomimes drew on the interest in classical culture, folklore and the exoticism of the Orient, «with here and there a touch of local colour»,[8] and consisted of two parts. The first and shorter section, the ‘opening’, was taken from classical mythology, nursery fables or popular legends, whereas the action of the second and longer part was centred on a love affair between Harlequin and Columbine. Their union was opposed by Columbine’s father and threatened by a foolish or sinister suitor, who chased the lovers through the streets of Georgian London to Mount Olympus, or to Hell, «with a total disregard for the limitations of time and space».[9]

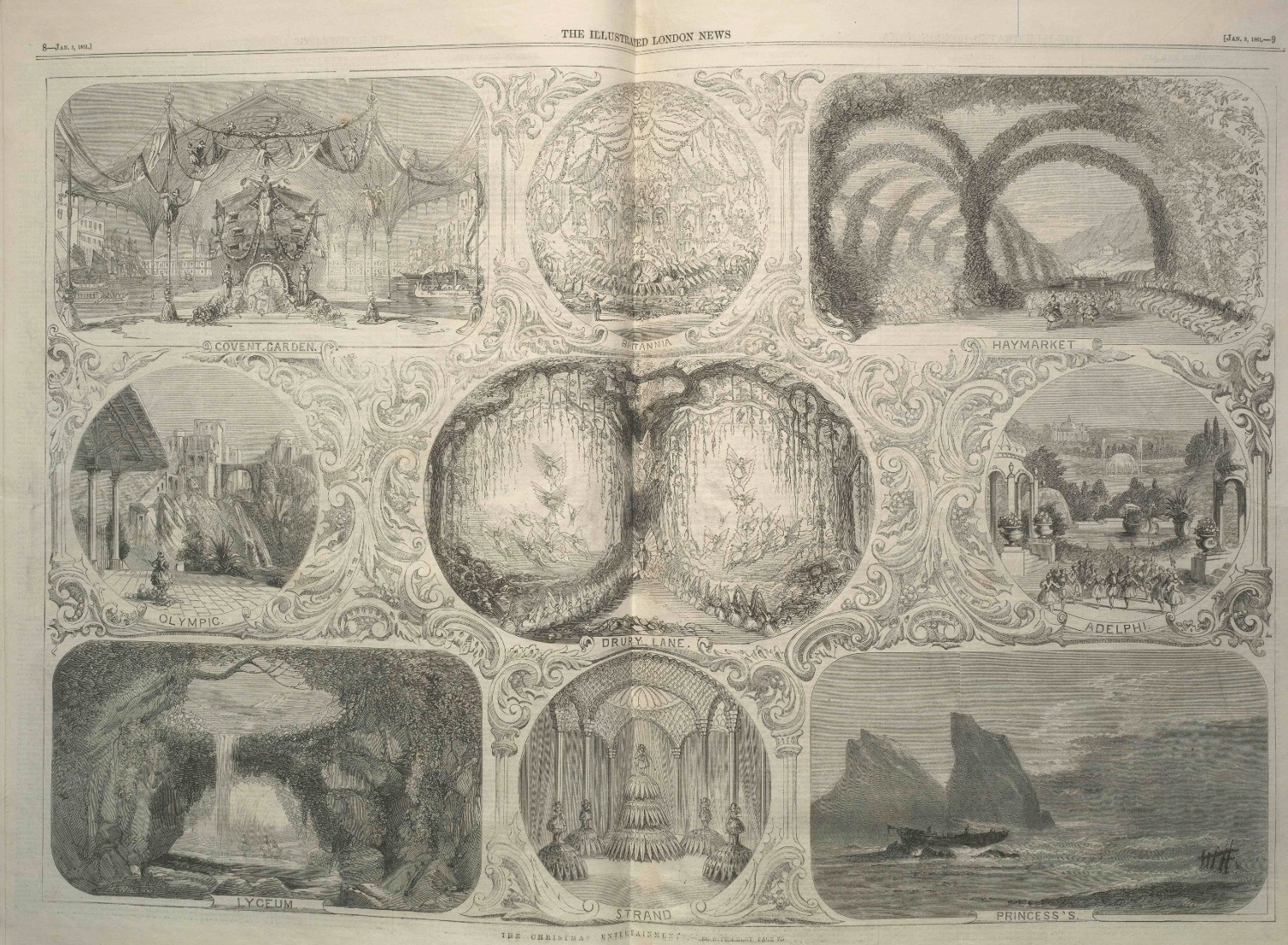

Another popular commedia character in the early pantomimes was the Clown, derived from the Italian Scaramouche, which Joseph Grimaldi together with the pantomime arrangers, Charles Farley, Thomas J. Dibdin and his brother Charles Dibdin, raised to the position of chief comic figure in the scenes of the Harlequinades from 1806 to 1823.[10] The success of Dibdin’s Harlequin and Mother Goose: or The Golden Egg (Covent Garden, 29 December 1806), with Grimaldi playing the Clown, brought about the increasing importance of the fairy-tale component in pantomime productions. As Michael Booth suggests, «it is no coincidence that […] the fairy element strengthened, and the harlequinade shortened as the interest in fairy culture grew and intensified in the 1830s and 1840s».[11] Starting with the coronation of Queen Victoria in 1837 and her marriage in 1840, which inaugurated a vogue for family life and introduced Christmas as the children’s festival, pantomime began to be regarded «as a family entertainment and as a significant facet of childhood experience».[12] By the late 1850s, pantomime performances also included visual and verbal references to contemporary city life, culture and politics that had a particular significance for local audiences.[13]

In the Victorian era, along with extravaganza and burlesque,[14] the pantomime became so overwhelmingly popular that it occupied second place in the pantheon of English drama, after Shakespeare’s plays. As one of the most critically aware and professionally innovative Victorian journalists, E.S. Dallas, affirmed in 1856, «the pantomime, and all that it includes of burlesque and extravaganza, is at present the great glory of the British drama».[15] The story of the pantomime’s development is infinitely more complex and fascinating than my summary sketch suggests, but what is worth emphasizing is that by 1870 pantomime librettists started to restrict themselves to a limited number of fairy-tale plots.[16]

2. From Illustrations to the Pantoland

If by the middle of the nineteenth century the tales by Charles Perrault and Madame d’Aulnoy were already well known to an English readership and used as the subject matter for fairy extravaganzas and burlettas (especially fine and sophisticated examples are those written by James Robinson Planché), the circumstance that further promoted the transposition of fairy tales to the British pantomime stage was the first English translation of the Grimms’ Kinder- und Hausmärchen. Between 1823 and 1826 Edgar Taylor published a two-volume set with a selection of the Grimms’ tales under the title German Popular Stories. Both volumes were illustrated by George Cruikshank, who contributed the title pages and twenty-two superb engravings. Taylor’s translation combined with Cruikshank’s gifted illustrations made the Grimms’ collection one of the most attractive and successful books of its time, to the point where, from the middle of the century, the German Popular Stories prevailed over Perrault and d’Aulnoy’s tales.

In his preface to the first volume, Taylor had already likened the translated tales to the English pantomime, both in terms of subject matter and audience: «they [wonder tales] are, like the Christmas Pantomimes, ostensibly brought forth to tickle the palate of the young, but often received with as keen an appetite by those of graver years».[17] However, what has not received the full attention of recent scholarship is that the illustrator of German Popular Stories, George Cruikshank (1792-1878), a prolific caricaturist, political satirist and the founder of pictorial journalism, was also profoundly inspired by theatrical culture in every period of his career.[18] Indeed, many of Cruikshank’s illustrations to the Grimms’ tales drew on a repertoire of posture, gesture and dramatic composition learnt from theatre, and shared the exaggeration and over-statement characteristic of theatrical melodrama and pantomime. Moreover, as far as the costuming of the fairy-tale characters is concerned, Cruikshank’s biographer Robert L. Patten points out that the illustrator relied neither on the German text, which rarely describes characters’ clothes, nor on antiquarian research into the costumes, but rather on English theatrical and pictorial precedents.[19]

Cruikshank’s etchings for the Grimms’ collection are also overshadowed by heavy curtains, ceilings, pediments and arches which recall the Victorian stage scenery and the proscenium arch, a structural feature of almost every theatre built in Britain from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century. Surrounded by these ponderous architectural elements and threatened by enormous masses of overhanging cloth, Cruikshank’s heroes «perform their little dramas».[20] Indeed, in his essay Quelques caricaturistes étrangers (1857), Charles Baudelaire made explicit the theatrical quality with which the artist endows his figures by evoking the pantomime: «Tous ses petits personnages miment avec fureur et turbulence comme des acteurs de pantomime. [...] Tout ce monde minuscule se culbute, s’agite et se mêle avec une pétulance indicible».[21] «A grotesque comedy constituted of pantomimic violence of gesture, expression»[22] and characters in motion – these are the essential characteristics of Cruikshank’s pictures. His illustrations of the Grimms’ tales thus served not only the function of decoration, but also that of re-situating the texts in another cultural context; and that context was decidedly theatrical.[23] Influenced by the theatrical background of their designer, the illustrations facilitated the transposition of the Grimms’ tales to the pantomime stage. As E.D.H. Johnson insightfully suggested, Cruikshank’s fanciful illustrations were what fixed once and for all «the way that English-speaking people think of fairyland».[24]

3. The Transposition of Fairy Tales to the Stage and the Structure of the Pantomime

But what happens to the original fairy tales once they are transposed to the Victorian Pantoland? Let us now examine what alterations the fairy tale undergoes in order to fit the generic conventions of the theatrical form, and to what extent its narrative structure is preserved when it is transferred into the semantic field of the performed pantomime. In my analysis, I will draw examples mainly from Cinderella, Bluebeard and The Sleeping Beauty pantomimes, a body of work large enough to constitute a fair sampling.

Generally, pantomime begins with an ‘Opening’ corresponding to the initial situation in the fairy tale as defined by Vladimir Propp in his influential Morphology of the Folktale (1928). The opening scene features the battle between demons and fairies, the forces of good and evil, who predict the breakdown of equilibrium and the potential for disaster. The examples are many, but I will cite only a few of them. In the opening scene of John Maddison Morton’s Harlequin Blue Beard, the great bashaw, or The good fairy triumphant over the demon of discord! (1854), Rustifusti, the demon of Discord, invites witches to help him fight the benevolent fairy. One of the witches warns him that Bluebeard’s life is in danger from his new wife’s curiosity. In Jay Hickory Wood’s and Arthur Collins’ 1901-2 production of Blue Beard at Drury Lane[25] the four winds are discussing the human flaws and decide to teach Fatima – soon to become Bluebeard’s wife – a lesson, for her only fault is curiosity. The opening of Hickory Wood’s and Collins’s Sleeping Beauty and the Beast (performed on 26 December 1900 at Drury Lane, with Dan Leno as Queen Ravia and Herbert Campbell as King Screwdolph) features the good fairies announcing the birth of the princess to the royal couple and the intrusion of the evil fairy pronouncing her curse.

The main part of the pantomime is spun around a familiar fairy tale, nursery rhyme or folktale and presents the basic plot of a selfish father or guardian who opposes his daughter’s or ward’s desire to marry the man she loves and instead offers her to a wealthy but ugly suitor. Indeed, in Morton’s Harlequin Blue Beard, Fatima is in love with Selim, but is sold by her father Mustapha to «the millionaire collector» Bluebeard at the Slave Market. A benevolent fairy intervenes and takes the young lovers under her protection. The couple triumph in the end thanks to a magical object which is given to them by the fairy. Adventures in which the young lovers are helped by the fairy agent to defeat the heroine’s father and the villain are combined with topical songs. The final scene celebrates the happy couple, and the pantomime ends with an elaborate ‘transformation scene’, in which the stage set slowly opens up and turns inside out to reveal a formerly hidden world of enchantment.

Pantomime has thus many structural similarities to fairy tales and has inherited many of their superficial attributes: wizards, witches, magic objects and talking animals. The relationship between the characters and their spheres of action also conforms to Propp’s scheme: the Fairy who provides the hero with magical gifts or another kind of protection is the Donor; Selim in Blue Beard and Prince Charming (or Caramel) in Cinderella and The Sleeping Beauty are the Heroes. We also have the princess and her father, whereas Cinderella’s ugly sisters and Sister Anne in the Bluebeard pantomimes are the melodramatic villains of the stories, since their desire to marry leads them to hate their siblings. Cinderella pantomimes also have the Helper in the figure of Buttons, the comic servant in the family house of Cinderella. Good and evil characters are clearly separated and identified. As in the classical fairy tales, there is no room for complexity or psychological development of character.

The majority of the pantomime productions take the fairy-tale story as shared knowledge to which they refer as an occasion for puns, comic scenes and techniques of sexual suggestion – as is the case, for example, in Hickory Wood’s Cinderella (1895). In the first scene of the first act, Lily and Gertrude Blarer, Cinderella’s ugly sisters and rivals for the attention of the prince, are arguing over which of them should go and look for the prince, who is hunting in the forest near their cottage. Lily, the younger sister, insists on going and that her sister should stay behind in order to «save her legs». The comic effect of the scene is obviously based on the audience’s familiarity with the fairy tale: the spectators indeed know in advance that the ugly sisters will not get the prince precisely because of the size of their legs. The sexual innuendo is easy to grasp, and the comic effect of the scene is reinforced by the fact that the ugly sisters are usually played by middle-aged male performers.

However, the competition for the theatre-going audience and the need to satisfy the public’s demand for novelty by updating the plots led to the pantomime becoming only loosely based on the original stories. It is not rare for it to combine not only two versions of the same tale by different authors, but also two different tales by two different authors. For instance, Hickory Wood’s scenario is a good example of the skilful blending of Perrault’s The Sleeping Beauty with Beauty and the Beast by Madame de Beaumont.[26] The tale of Beauty and the Beast was added to the plot of The Sleeping Beauty in order to extend the number of scenes and the range of locations to be staged. Since The Sleeping Beauty and the Beast is so little known, a brief plot summary might be in order. The first act tells the familiar story of the baby princess to whose christening the malignant fairy was accidentally not invited and of the spell consequently cast, in revenge, upon the unlucky infant. When the pantomime is apparently over, the story begins again: after the general awakening in the second act, no-one remembers the King and the Queen anymore since their kingdom has long since been replaced by a Republic. What is even more distressing is that the crown jewels are locked away in the museum, and the President refuses to hand them over. Princess Beauty and Prince Caramel prepare to marry, but the evil fairy Malivolentia re-appears and transforms him into The Beast. Disguised as burglars, the King and the Queen break into the museum and steal the crown jewels, but their escape is delayed when their car breaks down and falls to pieces (the ‘disintegrated’ car became a standard pantomime routine). Unfortunately, their efforts are in vain, for the villainous President has replaced the real crown jewels with paste substitutes, so Queen Ravia decides to cheer up their heartbroken daughter by taking home a rose from the garden they have wandered into. As she plucks it, the Beast appears and threatens to harm them unless Beauty returns the rose herself and marries him of her own will. Things get worse when the President throws them into jail, but in order to save them Beauty agrees to marry the Beast. After she departs, the President puts a tax on bicycles, and a revolution (led by the Nurse) breaks out. The President is overthrown and the King and the Queen are restored to the throne. Beauty returns the rose and kisses the Beast who at once is transformed back into Prince Caramel and all ends happily.

Another solid example of the fairy tale’s transformation in the passage from the narrative to the theatrical form, and of the ‘Englishing’ of the German tale is Edward Leman Blanchard’s Number Nip, or, Harlequin and the Gnome of the Giant Mountain (26 December 1866, Drury Lane). Blanchard, one of the most prolific pantomime writers from 1844 to 1888 and the author of highly literary scripts which conveyed in dramatic form the full atmosphere of their sources, enriched the popular legend of the gnome Rübezahl through the introduction of the Grimms’ story of The Elves and the Shoemaker. As Gerald Frow puts it, «as an exponent of fairy mythology for the little ones», Blanchard was viewed as «the Countess d’Aulnoy, Perrault, and the Brothers Grimm rolled into one».[27]

It is thus clear that, of the original story, only the basic plot outline remains, all the rest being re-imagined and re-mixed, either for comic purposes or in order to fit the conventions of pantomime. That the original fairy tale became scarcely recognisable is confirmed by the drama critic of The Athenaeum, who in his review refused to provide a summary of the Adelphi pantomime Harlequin and Little Bo-Peep; or, The Old Woman that lived in a shoe he had attended the evening before, recounting the following anecdote:

We remember once leaving Covent Garden, at the conclusion of a new play, in company with an Irish friend. The conversation naturally turned upon what we had just witnessed. Our friend’s first remark was, “I hope I’ll see the papers tomorrow.” “Why?” asked we. “I want to know what’s the plot.” – So may we truly say, we want to know the plot of the Adelphi harlequinade; for, though we have seen it, we must plead guilty to the minor offence of not knowing what it is about. However, there are many who, fortunately for managers, do not hold it at all necessary that their sense, as well as their senses, should be gratified by this species of representation: their motto at this season, like the Frenchman’s all the year round, is “il faut s’amuser;” and if that be effected, “the quomodo – the how,” is held of little moment.[28]

In the majority of cases the pantomime still conveys the familiar story, but the way the characters are developed goes completely against the literary source. The most significant change that the fairy tale undergoes in its transposition to the pantomime stage consists in the greater emphasis given to the love story, with the consequence that it becomes a comic equivalent of domestic melodrama. Hickory Wood and Collins’ Sleeping Beauty and the Beast offers a good example of pantomime’s creation of a romantic illusion that drew its audience into another world, a utopian transformation of their own reality:

PRINCE: Oh, if I only now could have the chance

To be an ancient hero of romance!

To rescue beauteous damsels in distress;

To serve from death some charming young Princess!

To overcome magicians in fair fight;

Put ogres, giants, wizards, all to flight!

Alas! The days of chivalry are fled,

And wizards, witches, fairies all are dead.

While as for me – I have been born too late –

For all the world is dull and up-to-date!

FAIRY QUEEN: Not so! True chivalry’s not dead, but sleeps,

And every heart some sweet romance still keeps;

The wish to be a hero still endures –

Wouldst truly like to test how strong is yours?

It is therefore the erotic tension that always generates the action, and this is also the reason why Bluebeard pantomimes deal less with the consequences of Bluebeard’s wife’s curiosity than with the love story between Fatima and Ibrahim and Sister Anne’s unsuccessful attempts to coax Bluebeard into matrimony.

The Victorian pantomime was thus anthological, mixing allusions to plot elements from many different tales, connected together with authorial additions, and blending seemingly incompatible elements within one genre.

4. Playing the Other: Cross-dressing in the Pantoland

In Pantoland, which is the carnival of the unacknowledged

and the fiesta of the repressed,

everything is excessive and gender is variable.

Angela Carter

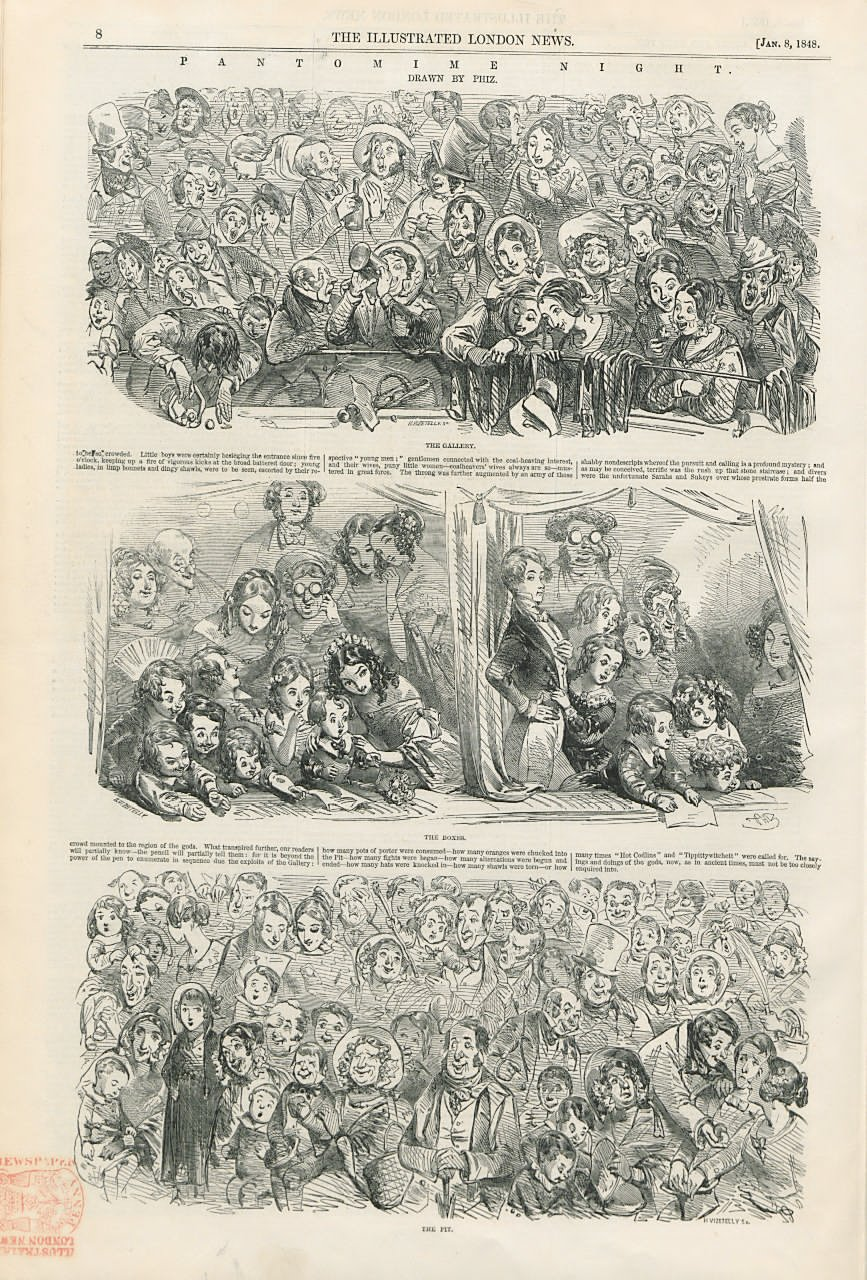

However, the broad popularity of the pantomime across generations and classes was based not only on the fairyland fantasy and romantic illusion that it offered to child spectators. As Samuel McKechnie has argued, «the laughter of children falls gratefully upon the ear, but no form of entertainment that would retain its popularity with grown-up people can afford to make its primary appeal to children. Not even the children appreciate the condescension […]».[29] Indeed, the reviews of pantomime productions as well as the illustrations in the periodicals show that the audiences consisted predominantly of adults.[30]

Apart from its dependence upon music-hall celebrities and topical allusions to current affairs and figures in the news, much of the pantomime’s appeal to adult audiences could be attributed to the comely transvestism of the actors. Thus, whereas children could enter a magical world of infinite possibilities and adventures, adults were invited into a world of gender subversion, since several of the key stock characters around which the action turned were played by cross-dressed performers. Indeed, the reason why adult audiences were so obsessed with the same few fairy-tale characters has much to do with the particular transvestite roles called the ‘Dame’ (who is a man) and the ‘Principal boy’ (played by a young, shapely female performer), which were added to pantomime performances around 1820. The Dame retains much of the grotesque fun of the Clown from the old pantomime practice, and plays the mother or stepmother of the hero (as in Jack and the Beanstalk, Aladdin, Little Red Riding-Hood and Snow White), but Dames may also play a governess or nurse (as in Hickory Wood’s Sleeping Beauty and the Beast). In Cinderella, the Dame roles are assigned to Cinderella’s sisters,[31] whereas in Bluebeard pantomimes both Sister Anne and Fatima, as well as Bluebeard’s older wives, are usually played by men. Whether a mother, nurse or sister, the Dame’s character remains essentially the same in every pantomime production: she is an unattractive, sexually transgressive, middle-aged woman with an adventurous spirit. Indeed, more often than not, pantomimes focus on the Dame’s sexual desire, which is portrayed as particularly ridiculous. Hickory Wood’s and Collins’ Blue Beard, with Dan Leno as Sister Anne, frustrated in her wish to marry the murderous Bluebeard (performed by Herbert Campbell), provides a fine example of the Dame’s functioning in the pantomime plot:

[SISTER ANNE]: If you could only see it, I’m the very wife for you! I shall make you an excellent wife – oh! you’ve no idea. See! There you are – a millionaire! Here am I – a lovable womanly woman. You absolutely don’t know what to do with your money. I do know what to do with your money, and I’ll do it, see? […] You’ll wonder how ever you managed to get on so long without me. […] Men don’t usually fall in love with me – not suddenly – I sort of grow on them – they glide gradually into love with me – but, when they’re once there, they’re there for ever – I’m a sort of a female rattlesnake. I weave spells round them – one of those – you know – those fog-horns you hear on the river – of course, I don’t mean I’m a fog-horn – but you know – tut, tut – Sirens – that’s it – I’m a Siren.

Similarly, in Hickory Wood’s Sleeping Beauty and the Beast, in the comic scene that features the court awakening from sleep, it is revealed that not only the beautiful protagonist waited a hundred years for her handsome husband, but her nurse as well. On her awakening she hears the blind man playing the song I’ll be your sweetheart if you will be mine and mistakes him for the long-awaited lover: «Take me! I am yours», she promptly exclaims. To the nurse’s disappointment, the Blind man is unfortunately already married: «Oh, dear! Here have I been asleep for a hundred years, and dreaming that a true lover would come and wake me with a kiss. I thought I had found him at last. What a terrible disappointment!» (p. 414). As Edwin Eigner argues, «the Dame thus retains much more of Clown’s sexuality than one would expect in a children’s show».[32]

Another transvestite role, which was introduced in the Regency pantomime and conserved throughout the Victorian era, is that of the Principal boy. Among the pantomime principal boys are Prince Charming and Dandini in Cinderella and Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Jack in Jack and the Beanstalk, Selim, the lover of Bluebeard’s wife, as well as Boy Blue in Little Red Riding Hood. An actress in pantomime did not impersonate a man, but retained her femininity in the role, wearing short and flattering costumes which prominently displayed her legs. As Jane Stedman notes, «[m]id-Victorians, irresistibly attracted to legs, watched the costume of the principal boys rise from near-knee-length in the 1860s to silken thighs in the 1870s».[33]

Theatre has always been a privileged site of transgression, but the pantomime stage, with its representation of a world where girls are boys and men are Dames, blurred all the distinctions between sexual identities. Although neither the Dame’s male impersonator nor the Principal boy inverted the traditional gender order, each of them disrupted it, calling attention to all that remains unsatisfied, repressed, or disturbing. As Marjorie Garber points out in her fine study, Vested Interests, cross-dressing is always intensely problematic for patriarchal cultures, since it reveals deep-seated anxieties concerning the possibility that gender is not fixed. For Garber, «transvestism is a space of possibility structuring and confounding culture: the disrupting element that intervenes, not just a category crisis of male and female, but the crisis of category itself».[34] In other words, cross-dressing reveals how gender is symbolically constructed and strikes at the heart of the social imperative to categorise individuals by rank.[35] As a theatrically extreme form of fantasy, the Victorian pantomime thus functioned as a forum for exploring sexual boundaries and interrogating the meanings of gender. But Garber goes on to suggest that the «capacity for realization onstage lies within the text, that it is not imposed from outside, as a foreign, unwelcome or overingenious overlay».[36] The pantomime cross-dressed casting is therefore not only the expression of anxiety related to the representation of gender in the Victorian era, but a back-formation, a return to the problem of the way the categories of masculine and feminine are treated in the fairy tales.

Although seldom represented, the cross-dressing motif has always been present in fairy-tale collections. It is sufficient, indeed, to recall the infamous wolf dressing up as the grandmother in order to trick Little Red Riding Hood. Among the few other men who cross-dress are also the devil, adulterers and thieves. What is more interesting for the purposes of the present investigation is that the Grimm Brothers adopted from medieval legends and hagiographical accounts the motif of the persecuted maiden who disguised her gender in order to escape sexual abuse or incestuous passions (Allerleirauh and Princessin Mäusehaut), to avoid enforced marriages (Die heilige Frau Kummernis), or in order to take part in the male realm.[37] These tales of female cross-dressing clearly betray a desire to acknowledge or create models of female heroism and Christian perfection in women. Indeed, their cross-dressed heroines do not create disorder by shifting gender, rather they assume male power in order to restore stability, which male authorities in the story have failed to secure. Although the disguise in the Grimms’ narratives is only temporary and the tales inevitably end when the girl’s identity is disclosed and the heroine reverts to her female attire, they turn on ambiguity of gender identity, exposing the anxiety of the Brothers Grimm regarding the stability of gender and women’s roles. As Laurence Senelick argues, the «very act of assuming a persona other than one’s own is bound to provoke a disruption or defiance of the ‘normal’ state of things: shape-changing is magical by definition, but gender-changing is exceptionally potent».[38]

At this point it is interesting to examine whether the pantomime transvestite characters conform to the Grimms’ and Perrault’s conservative notions of a strict gender hierarchy,[39] or do they, instead, question the social order and create new ways of conceptualising sexuality? Some critics have suggested that one way of viewing the pantomime’s gender play would be to see it as a British way of periodically breaking social rules in the safe enclosure of the theatre, as an outlet for Victorians greatly concerned with self-improvement and self-discipline.[40] When viewed as an aspect of the carnivalesque,[41] pantomime becomes an arena for the replacement of order by chaos, an inversion of imposed gender roles and a celebration of the repressed. However, if gender identity was able to be safely questioned, constructed and reconstructed in pantomime, did this theatrical form also contain subversive implications for off-stage behaviour? In other words, did the Victorian pantomime represent only a dramatic illusion, or, on the contrary, did it serve as a useful measure of popular perceptions of contemporary gender issues?

Jim Davis argues that, in the Victorian era, the popularity of pantomime as well as other theatrical forms of popular entertainment, such as burlesque and farce, which also featured cross-dressing casting, testifies to the fact they «also functioned as a way of seeing, even as metaphor, in shaping perceptions of the contemporary world in just as forceful a way as has long been credited to melodrama».[42] In this light, the Principal boy showing ‘her’ legs itself broke Victorian conventions of displaying the body and, as Kathy Fletcher points out, even if the actress did not appear in contemporary male costume, dispensing with the voluminous Victorian petticoats that were a physical representation of the prohibitive rules for respectable feminine behaviour was in some way symbolic and put in question the naturalness of traditional constructions of gender hierarchy. It meant increased freedom of movement and action and, by implication, the assumption of male autonomy.[43] Without violating the sexual boundaries related to gender-specific behaviour, the Principal boy could in fact do all kinds of things that the Victorian girl was forbidden to do: he could kill dragons and monsters, outwit enemies and rescue maidens. As Angela Carter puts it, the principal boy «is played for thrills, for adventure, for romance».[44] If we consider another transvestite role in pantomime, the Dame, where a middle-aged man impersonates a grotesque and sex-starved woman at the same time retaining his male identity, it is clear that the character’s function is linked to both the male performer’s burlesquing of himself as a male actor in female attire and to men’s deep ambivalence towards women. This role is thus multivalent. But if to dress as a woman means to temporarily become one, then, as Peter Holland suggests, by becoming a woman one can explore male attitudes towards women and understand female psychology.[45] The costumes thus possess a kind of social reality and authority, where the cross-dressed performers can revolutionise the nature of the dramatic illusion. They cease to be female or male impersonators and become an image of artistic freedom.[46] The contradictory responses to Victorian pantomime performances attest to the subversive implications of this theatrical form. In an article entitled ‘The Decline of Pantomime’, William Davenport Adams, the theatre historian and the author of an important study on burlesque, attacked the pantomime precisely because of its cross-dressed roles and the convention of sexual display:

[…] the chief object of the entrepreneur appears to be to put men into women’s parts, and women’s into men’s, and, at the same time, to make as great a display as possible of the feminine form. […] I am quite sure that it is a vicious object on the part of one who ostensibly provides a holiday entertainment for “the children”. A man in woman’s clothes cannot but be more or less vulgar, and a woman in male attire, of the burlesque and pantomime description, cannot but appear indelicate to those who have not been hardened to such sights. […] Over and over again must mothers have blushed (if they were able to do so) at the exhibition of female anatomy to which the “highly respectable” pantomime has introduced their children. […] And, as regards the principals in pantomime, why must the hero always be a woman dressed in tights and tunic? And why must the comic “old woman” always be a man?”[47]

This passage tends to confirm Holland’s view that «the concept of panto as designed for children was a convenient fiction, a protection of the adults both from the embarrassment of admitting their pleasure in folk tales but also from the open avowal of the vulgar sexuality of panto humour».[48] The freedom of the Victorian pantomime was thus not in its reversal of power, as in the carnival practices, but in suspending oppressive constructions of difference and in the illusion of gender performativity that it provided to its adult audiences.

The last question that I would like to examine is whether transvestite performances in pantomime influenced gender discourse in Victorian England. Did the audience interaction with the performers, which was (and still is) greatly encouraged during the pantomime performance, manage to shape Victorian awareness of the instability of gender definitions? Despite the difficulty of reconstructing the impact of pantomimes on their audiences from the scripts and press reviews, which more often than not bore little relationship to what actually happened on stage, in a period when caricaturists often used pantomime images for political and social satire,[49] an extra-theatrical significance was surely embedded in pantomimes. My argument is at odds with what is generally presumed about pantomime’s influence on changing or improving the world outside the theatre,[50] but theatricality was the Zeitgeist of this age, a metaphor that encouraged spectators to view the world as if it were a stage-set on which humanity played and watched itself play.[51] The pantomime’s multivalent construction of transvestite performance could thus lead its audience to revisit the heterosexual ideology and prescribed social roles and identities and «to consider the potential existence of other ontological possibilities that may have remained unarticulated».[52] If we also take into account the public expression of homosexuality among a small group of courageous pioneers, including Oscar Wilde’s subversion of male dress by adopting feminine styles, drawing repeatedly on theatrical prototypes from mainstream entertainments, such as parody, burlesque and pantomime (all of which «based their humour on erotically inflected rhetoric and images of apparent deviancy - such as male effeminacy and overt female sexuality»),[53] it seems plausible to conclude that pantomime assumed an extraordinary power as an agent of destabilisation, desire and fantasy. Its use of cross-dressed casts «helped establish havens of ambiguity in which marginalised sexual identities were given room to develop»,[54] but it also offered the general public a way out of, or around, the binary system of gender.

The nineteenth-century fairy-tale pantomime is thus a sound example of the history of the fairy-tale genre as one of continual evolution and re-invention, where the old fairy tale narratives are continuously recycled and re-elaborated in order to suit cultural needs and anxieties. The appropriation of fairy tales by pantomimes also exemplifies their enormous subversive potential. While the nature of this subversion may vary depending on the society in which fairy tales appear and on the choice of genre, it seems legitimate to conclude that the fairy pantomime practices were vital if not in breaking down the rigidly stratified notions of gender held by the public at large, then at least in foregrounding the constructedness of the ideological preconceptions behind it.

Pantomimes cited

1806 Harlequin and Mother Goose; or, The Golden Egg; Covent Garden; December 29; Thomas J. Dibdin.

1873 Red Riding Hood and her sister little Bo-Peep; Covent Garden; Charles Rice. Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

1854 Harlequin Blue Beard, the great bashaw, or The good fairy triumphant over the demon of discord! A grand Comic Christmas Pantomime; John Maddison Morton. Royal Princess’s Theatre; 26 December.

1895 Cinderella; Jay Hickory Wood. Drury Lane; Reprinted in: Leach, Robert. Pantomime Playtexts. London: Harrap, 1980.

1901-2 Blue Beard. Theatre Royal Drury Lane; J. Hickory Wood and Arthur Collins. Victoria and Albert Museum.

1900 The Sleeping Beauty and the Beast. A Grand Christmas Pantomime; Drury Lane; 26 December 1900; Jay Hickory Wood and Arthur Collins.

* My sincere thanks are due to the Sackler Library for granting permission to reproduce the illustrations in this article. The research for this article was supported by a John Griffith Fellowship from Jesus College Oxford (summer, 2013).

1 The complex relations between pantomime and fairy tales have so far received scant scholarly attention; Jennifer Schacker has so far been the only one to attempt to bridge the gap between studies of the fairy-tale genre and its pantomime renditions. See J. Schacker, ‘The Economics and Erotics of Fairy-Tale Pantomime’, Marvels & Tales: Journal of Fairy-Tale Studies, 26.2 (2012), pp. 153-77 and ‘Slaying Blunderboer. Cross-Dressed Heroes, National Identities and Wartime Pantomime’, Marvels & Tales: Journal of Fairy-Tale Studies, 27.1 (2013), pp. 52-64.

2 On the pre-Victorian Regency pantomime, see David Mayer’s 1969 book, Harlequin in his Element: The English Pantomime 1806-1836, Cambridge, Mass., Harvard UP, 1995 and J. O’Brien, Harlequin Britain: Pantomime and Entertainment 1690-1760, Baltimore-London, Johns Hopkins UP, 2004. For the principal works on nineteenth-century pantomime, see M. Booth, Victorian Spectacular Theatre, London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1981, and Theatre in the Victorian Age, Cambridge, CUP, 1991; A.E. Wilson, Pantomime Pageant. A Procession of Harlequins, Clowns, Comedians, Principal Boys, Pantomime-writers, Producers and Playgoes, London-New York, Stanley Paul, 1946.

3 L. Wagner, The Pantomimes and All About Them, London, J. Heywood, 1881, p. 27.

4 Ivi, p. 31; A.E. Wilson, Pantomime Pageant, cit., p. 15.

5 Rich’s first foray into the emerging genre of pantomime was Harlequin Executed; or, The Farmer Disappointed, which represented a response to The Whimsical Death of Harlequin, produced at Drury Lane. See M. Goff, ‘John Rich, French Dancing and English Pantomimes’, in B. Joncus, J. Barlow (eds.), “The Stage’s Glory”. John Rich, 1692-1761, Newark, University of Delaware Press, 2011, pp. 85-98, here p. 89.

6 J. O’Brien, Harlequin Britain, p. xxiv.

7 D. Mayer, Harlequin in his Element, p. 19.

8 T. Niklaus, Harlequin Phoenix, or The Rise and Fall of a Bergamask Rogue, London, The Bodley Head, 1956, p. 136.

9 Ibidem.

10 D. Mayer, Harlequin in his Element, p. 28.

11 M. Booth, Victorian Spectacular Theatre, p. 75.

12 J. Davis, Introduction: Victorian Pantomime, in Id. (ed.), Victorian Pantomime: A Collection of Critical Essays, London, Palgrave Macmillan, 2010, p. 5.

13 J.A. Sullivan, The Politics of the Pantomime. Regional Identity in the Theatre, 1860-1900, Hatfield, University of Hertfordshire Press, 2011, p. 179.

14 According to the definition given by Carolyn Williams, «both burlesque and extravaganza are themselves forms of parody». While «in nineteenth-century England, the term burlesque indicated the mock-heroic deflation of a particular work belonging to a higher tradition of literature or music», extravaganza was a pantomime without harlequinade, «a burlesque weakened into farce with no critical purpose, a whimsical entertainment conducted in rhymed couplets or blank verse, garnished with puns, and normally concerned with classical heroes or fairy-tale characters or plots» (C. Williams, Gilbert & Sullivan. Gender, Genre, Parody, New York, Columbia UP, 2011, p. 376).

15 E.S. Dallas, ‘The Drama’, Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, 79, February 1856, p. 210.

16 T. Niklaus, Harlequin Phoenix, p. 169.

17 J. and W. Grimm, German Popular Stories, Translated from the Kinder und Haus-Marchen [sic], Collected by MM. Grimm, from Oral Tradition, London, C. Baldwyn, 1823, I, p. 2.

18 In his early years, Cruikshank did a good deal of amateur acting and for a time harboured a desire to turn professional. He executed theatre backdrops for Drury Lane theatre, juvenile theatre sheets, and twenty-one coloured plates of leading actors of the day for Thomas Kenrick’s The British Stage and Literary Cabinet (1817-22), and also illustrated Charles Dickens’s Memoirs of Joseph Grimaldi.

19 R.L. Patten, George Cruikshank’s Grimm Humor, in J. Möller (ed.), Imagination on a Long Rein. English Literature Illustrated, Marburg, Jonas, 1988, p. 20.

20 J.H. Miller, D. Borrowitz, Charles Dickens and George Cruikshank, Los Angeles, Clark Memorial Library, 1971, p. 57. The scholars apply this definition to Cruikshank’s illustrations to Sketches by Boz, but the description also holds true with regard to the artist’s pictures for the Grimms’ collection.

21 C. Baudelaire, Quelques caricaturistes étrangers. Hogarth-Cruikshank-Goya-Pinelli-Brughel, in Id., Oeuvres complètes, par C. Pichois, Paris, Gallimard, 1975, II, pp. 566-567.

22 J.H. Miller, D. Borrowitz, Charles Dickens and George Cruikshank, p. 57.

23 As Michael Booth has argued, Victorian culture was marked by a taste for visual spectacle which extended into all areas of cultural life: «An immediate and striking use of painting in the theatre was the widespread practice of ‘realising’ famous paintings by combinations of actors, scenery, and properties in imitation of the paintings themselves. This practice seems to have begun in the 1830s, although it may have been earlier, and lasted into the twentieth century» (M. Booth, Victorian Spectacular Theatre, p. 9).

24 E.D.H. Johnson, The George Cruikshank Collection at Princeton, in R.L. Patten (ed.), George Cruikshank: A Revaluation, Princeton, N.J, Princeton University Library Chronicle, 1974, p. 9.

25 The outstanding pantomime librettist Jay Hickory Wood (pseudonym of John James Wood, 1858-1913) wrote the plots to highlight the talents of Dan Leno, the most celebrated male performer of Victorian music hall and Drury Lane pantomime star.

26 Although this pantomime was highly successful, enjoying 136 performances (interrupted for four days in January 1901 by the death and funeral of Queen Victoria), not all Victorian critics were pleased with such re-mixing of different plotlines, especially for audiences of children. Writing in 1882, Davenport Adams complained about the pantomimes’ arrangers’ unfaithfulness to the sources of plots: «There would not, however, be so much objection to adhering to the old familiar nursery tales, if those tales were only treated by librettists and managers in a becoming spirit. I write in the interest of the children. Adults may not, in every case, object greatly to the medication introduced into the separate legends, or to the amalgamation of several legends into one. […] how singularly disagreeable they must be to the young imagination of our boys and girls, for whom Dick Whittington, Aladdin, Red Riding Hood, and Bo-peep, are almost as real and vivid as their own relations! How keenly they must, and no doubt do, resent the liberties taken with narratives which they know by heart, and which they cherish as a part of their juvenile religion! […] It is bad enough that such familiar tales should be modified by librettists as they so often are; it is worse when a tale is incorporated with others, and when the result is so thoroughly mixed up that the juvenile intellect cannot make head nor tail of it» (W. Davenport Adams, ‘The Decline of Pantomime’, The Theatre, vol. V. 1, February 1882, p. 88).

27 G. Frow, Oh Yes It Is! A History of Pantomime, London, BBC, 1985, p. 14.

28 ‘The pantomimes’, The Athenaeum, 31 December 1832, p. 852.

29 S. McKechnie, Popular Entertainment Through the Ages, London, Sampson, Low, Marston & Co., 1931, p. 131.

30 The anonymous reviewer of The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News recounts that his attempt to see The Sleeping Beauty and the Beast was only «partially successful» because of the great quantity of ladies who made it impossible «to get an idea of the dancers, and even the singers». He notes that fortunately «there were not many children in either stalls or pit, or they would of course have been even greater sufferers than the rest of us, from the egregious selfishness of their sisters, their mothers, and their aunts» (‘Our captious critic. Sleeping Beauty and the Beast’, The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, 12 January 1901, p. 756).

31 The characters of ugly sisters (together with Buttons) were added to Cinderella pantomime in 1860 by H.J. Byron, the most prolific mid-Victorian writer of pantomimes and burlesques, and were originally called Clorinda and Thisbe.

32 E.M. Eigner, ‘Imps, Dames and Principal Boys: Gender Confusion in the Nineteenth-Century Pantomime’, Browning Institute Studies, 17 (1989), pp. 65-74, here p. 73.

33 J.W. Stedman, ‘From Dame to Woman: W.S. Gilbert and Theatrical Transvestism’, Victorian Studies, 14.1 (1970), pp. 27-46, here p. 29.

34 M. Garber, Vested Interests: Cross-Dressing and Cultural Anxiety, New York, Routledge, 1992, p. 32.

35 Ivi, p. 17.

36 Ivi, p. 39.

37 The portrayals of many heroines in the Grimms’ Kinder- und Hausmärchen and Deutsche Sagen bear striking similarities to the tribulations of female martyrs: the mutilation of the heroine’s hands in Das Mädchen ohne Hände resembles the Saint Oliva legend, whereas the plotline of Schneewitchen is similar to the sacred representation of Estelle.

38 L. Senelick, The Changing Room: Sex, Drag and Theatre, London, Routledge, 2000, p. 17.

39 In general, fairy tales by French women writers, such as Madame d’Aulnoy, whose tales were frequently adapted for fairy extravaganzas and Christmas pantomimes, were more progressive in their re-thinking of the categories of gender and identity than the tales by male writers. See T. Korneeva, ‘Rival Sisters and Vengeance Motifs in the contes des fées of d’Aulnoy, Lhéritier and Perrault’, MLN, 127.4 (2012), pp. 732-53.

40 See, for example, Eigner, ‘Imps, Dames and Principal Boys’, p. 73; K. Fletcher, ‘Planché, Vestris, and the Transvestite Role: Sexuality and Gender in Victorian Popular Theatre’, Nineteenth-Century Theatre, 15.1 (1987), p. 32.

41 On the notion of ‘carnivalesque’, see M. Bakhtin, Rabelais and his World (Cambridge, MA, MIT Press, 1968; P. Stallybrass and A. White, The Politics and Poetics of Transgression, London, Methuen, 1986, esp. Chapter 5.

42 J. Davis, Introduction: Victorian Pantomime, p. 2.

43 K. Fletcher, Planché, Vestris, and the Transvestite Role, cit., p. 28.

44 A. Carter, In Pantoland, in Ead., American Ghosts & Old World Wonders, London, Chatto & Windus, 1993, p. 107.

45 P. Holland, ‘The Play of Eros: Paradoxes of Gender in English Pantomime’, New Theatre Quarterly, 13 (1997), pp. 195-204, here p. 203.

46 See N. Zemon Davis, “Women On Top”, in Ead., Society and Culture in Early Modern France. Stanford, Stanford UP, 1975, pp. 124-51. Natalie Zemon Davis’s ground-breaking essay on symbolic sexual inversion and the image of unruly woman in literature and popular festivities, has shown that the practice of male-to-female cross-dressing, aimed to ridicule women, was nonetheless used for explicit critique of social and gender order. See also P. Ackroyd, Dressing up: Transvestism and Drag: The History of an Obsession, New York, Simon and Schuster, 1979, p. 122.

47 W. Davenport Adams The Theatre, n.s., vol. V. 1, February 1882, p. 89.

48 P. Holland, The Play of Eros, p. 203.

49 See J. O’Brien, Harlequin Britain, p. xix: «To tell pantomime story then, is to tell the story, not just of the eighteenth-century theatre, but of British culture more broadly, of the way that the concept of entertainment seemed to claim an increasingly large share of the public sphere. One result of this phenomenon was that, as we shall see, issues of state – for example, ministerial politics, the system of justice – seemed to be modelling themselves on the theatre rather than the other way around».

50 See, for example, N. Bown (Fairies in Nineteenth century Art and Literature, Cambridge-New York, CUP, 2001, p. 11), who claims that «fairies probably never helped the Victorians make important moral, political, economic or religious decisions; they never sprinkled fairy dust over poverty, disease, oppression, cruelty or neglect; there is neither call nor need in fairyland for empire or reform».

51 On how the idea of theatre was embedded within late eighteenth- and nineteenth-century sensibility and on a theatrical representation of life, see G. McGillivray, ‘The Picturesque World Stage’, Performance Research, 13.4 (2008), pp. 127-39.

52 D. Denisoff, Aestheticism and Sexual Parody, Cambridge, CUP, 2001, p. 4.

53 Ivi, p. 9.

54 Ibidem.