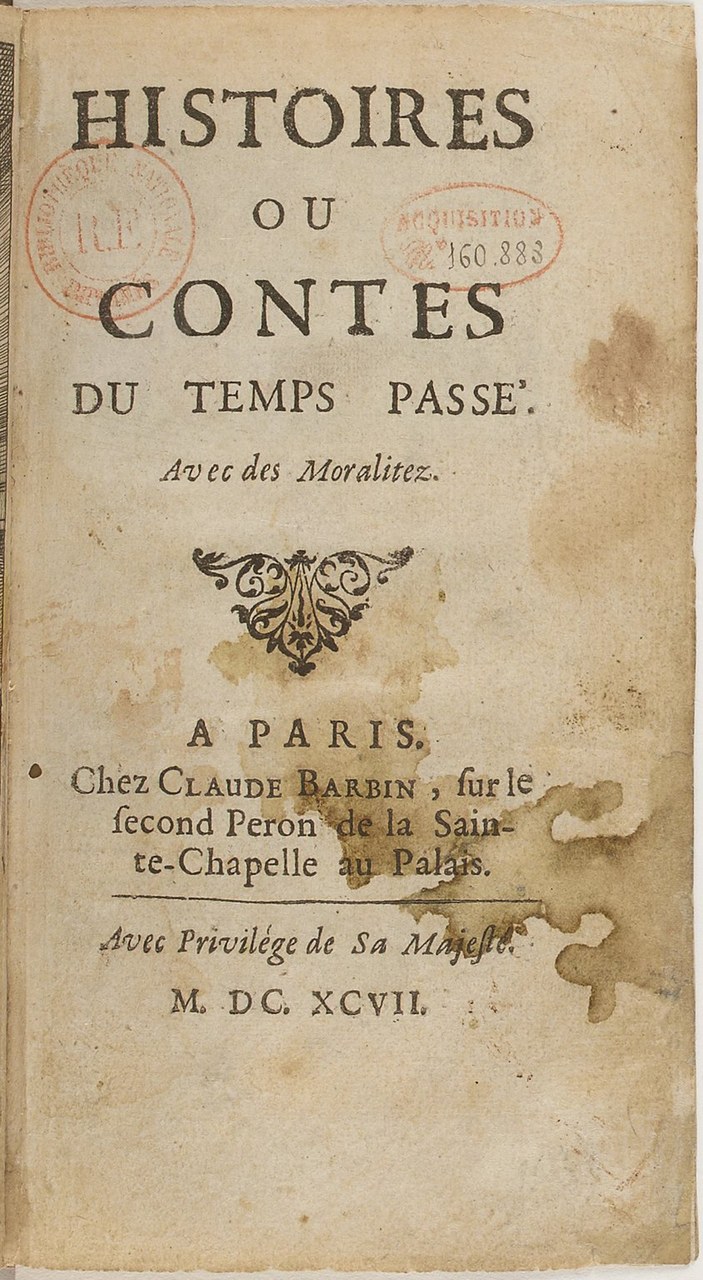

Barbablù fa il suo ingresso nel teatro e nella letteratura tedeschi grazie alla favola teatrale di Ludwig Tieck (edita in quattro atti nel 1797, poi in cinque nel 1812). Rudolf Haym (1870, pp. 90 sgg.), giudicava l’impresa intrinsecamente impossibile: la dimensione fantastica e illogica della fiaba sarebbe costitutivamente incompatibile con i rapporti di causalità e il realismo richiesti dalla scena, sicché Blaubart potrebbe essere tollerato in teatro, grazie al potere de-realizzante della comicità e della musica, tutt’al più come musikalische Zauberposse (farsa magica in musica). Il dramma di Tieck conobbe effettivamente una fortuna scenica particolarmente scarsa a suo tempo, e nel Novecento (il secolo che pure ha reso possibile spesso in teatro ciò che in passato era ritenuto impossibile) esitò addirittura in un terribile Theaterskandal (Residenztheater di Monaco, regia di Jürgen Fehling, 1951).

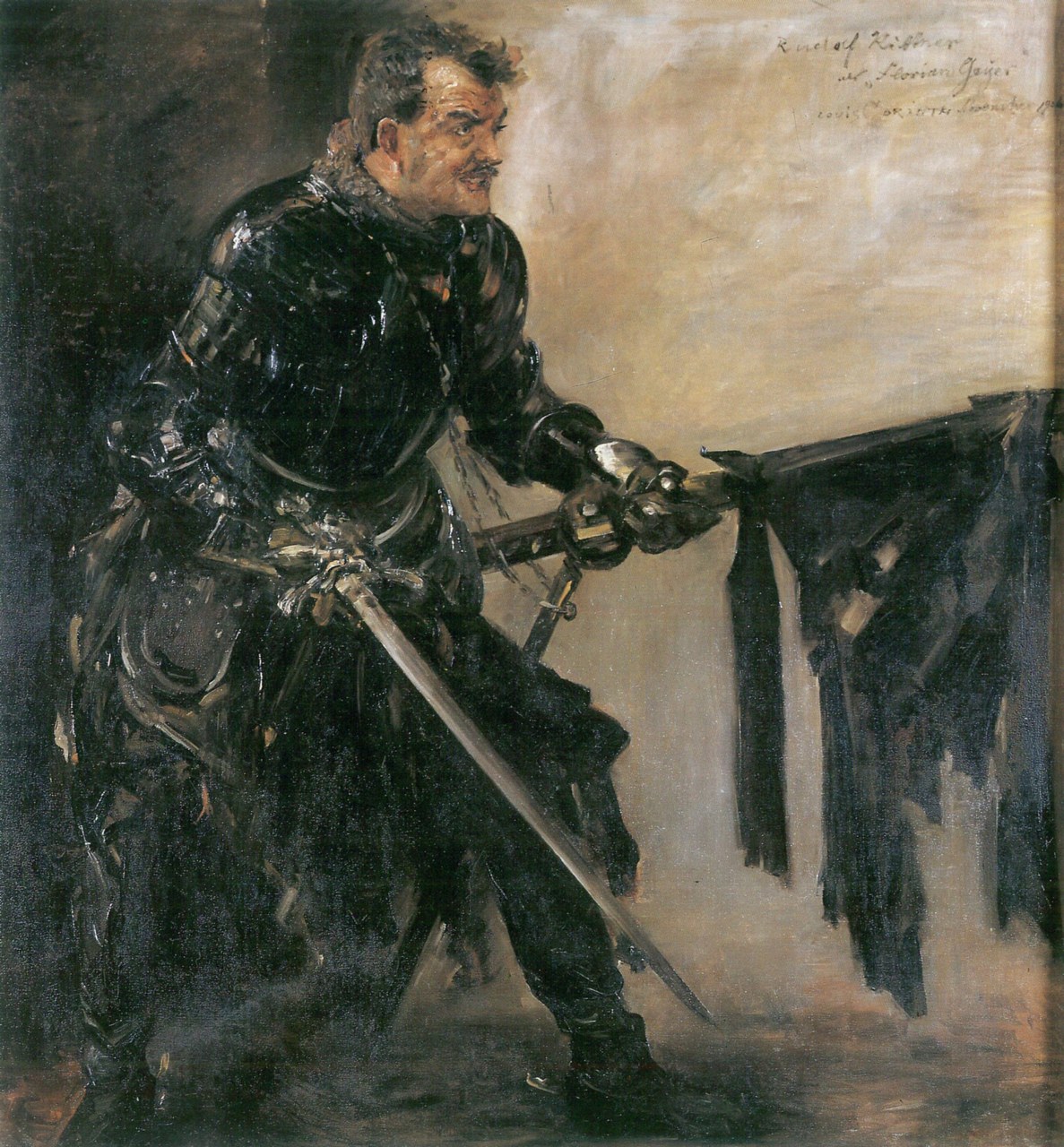

Il caso di Herbert Eulenberg, dunque, sembra paradigmatico alla luce di tali premesse: rappresentato nel 1906 come dramma in prosa, il suo Barbablù si dimostrò un solenne fiasco e un eclatante Theaterskandal; riproposto nel 1920, questa volta riadattato a libretto per la musica di Rezniceck, riscosse invece un discreto successo [fig. 1]. Quando nel 1905 pubblica Ritter Blaubart (Cavaliere Barbablù) Eulenberg – autore oggi pressoché dimenticato o ricordato come degno di oblio, ma che, soprattutto tra il 1910 e l’inizio della prima guerra mondiale, godette di larghissimo favore sulle scene tedesche – era praticamente uno sconosciuto per i grandi teatri di Berlino. Improvvisamente i due maggiori uomini di teatro dell’epoca, Otto Brahm e Max Reinhardt, s’interessano al suo testo. Il primo portando nel 1889 gli Spettri di Henrik Ibsen e Prima dell’alba di Gerhard Hauptmann (epocale scandalo teatrale) alla Freie Bühne aveva ‘rivoluzionato’ le scene tedesche e inaugurato il naturalismo; il secondo, formatosi alla scuola di Brahm, era diventato il regista antinaturalista per eccellenza, deciso a bandire il grigiore della vita quotidiana e a recuperare la magia dello spettacolo.